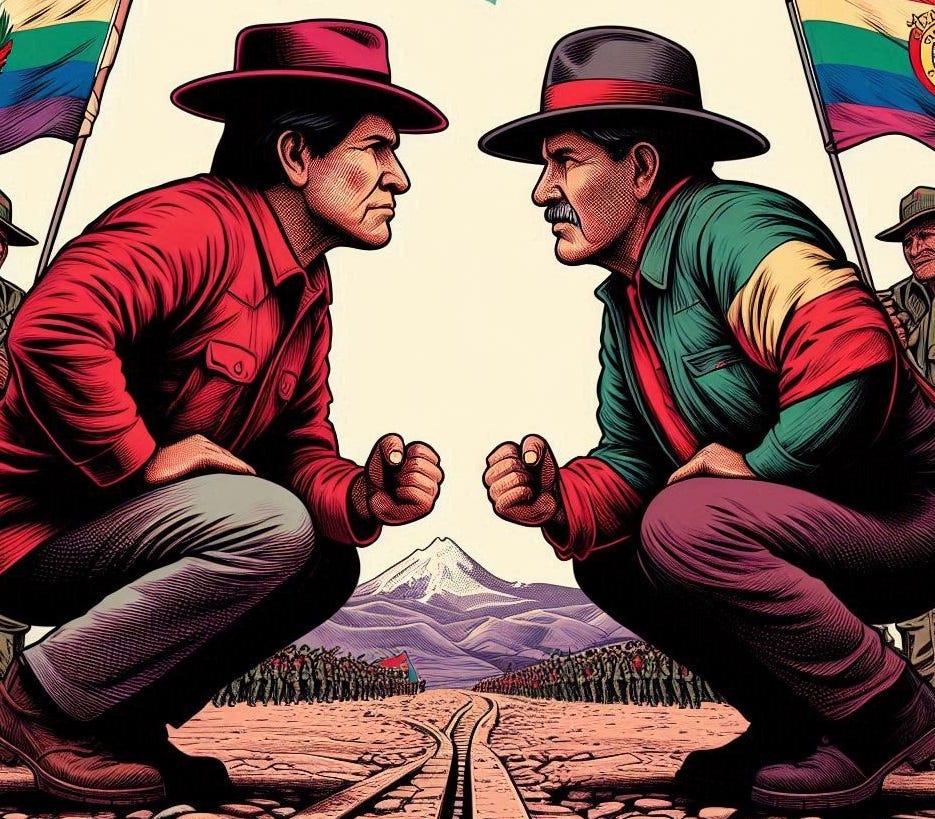

Bolivia's Left is engaged in a blood feud that could mean the end of MAS rule

President Arce and Evo Morales in a "catastrophic stalemate" as economic crises worsen

This week’s feature is by Jordan Cooper, a sociologist in Bolivia who works with indigenous peoples.

The blood feud between Bolivia’s current president Luis Arce Catacora and former president Evo Morales over control of the ruling Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party reached a fever pitch this week as roadblocks by Evo supporters paralyzed much of the country and led to running battles with police.

Since Monday, October 14, social movements, unions, and other Evista (followers of Evo Morales) sectors have been blocking roads in the Cochabamba department in Bolivia’s geographical center. Evo supporters have set up roadblocks on the thoroughfares connecting the main population centers of La Paz and El Alto in the West with Santa Cruz in the East.

Tension among protesters has grown in recent days after Evo Morales survived an apparent assassination attempt when the car he was traveling in near Shinahota, Cochabamba came under gunfire on the morning of October 27.

While Morales has blamed Minister of Government Eduardo del Castillo for ordering an attempt on his life, the government has contended that Evo’s vehicles attempted to evade a routine anti-narcotics check, running over a police officer and opening fire first.

Blockades, confrontations with police, and heightened tensions

As the power struggle between Morales and Arce for control of Bolivia’s leftist MAS party continues, blockaders and police fight pitched battles in which security forces are often outgunned and overpowered. Police use tear gas while blockaders respond with rocks and dynamite. In one clash at Parotani, an explosion resulted in a police officer losing part of his leg.

Morales supporters Cochabamba have also taken over 3 military installations and taken soldiers hostage. The Foreign Affairs ministry denounced the occupations to the international community, noting that at least 200 military personnel were held hostage. They have since been released and the government has re-established control over the bases.

In Parotani, in the Cochabamba department, 55 people have been arrested so far, 21 of whom are facing terrorism charges.

In Mairana, Santa Cruz department, protesters and police exchanged hostages —arrested blockaders for captured police officers and journalists.

Bolivia is living through the beginning of what will likely be a severe and long-term economic crisis, and the blockades have exacerbated existing problems. Prices of basic goods and fuel have risen dramatically. Gasoline and diesel are so scarce that drivers wait in line sometimes for days, and the country’s foreign exchange reserves are practically dry.

Chicken and other food is very expensive, as it cannot travel from Santa Cruz to La Paz due to the blockades. The government has arranged airlifts of chicken in an attempt to alleviate shortages, but the shortages and high prices have persisted.

The motivations behind Evo’s protests are twofold: to force the government to legalize his presidential candidacy, which the Bolivian Constitution currently prohibits, and to suspend the legal proceedings against him pertaining to several cases of alleged statutory rape and human trafficking.

Prominent Evista senator Leonardo Loza appeared to confirm that the blockades were motivated by Evo’s personal troubles when he said on October 16 that “the blockades could end today. What would it cost the government to lift all of the criminal processes?”.

Evo and his supporters say the criminal charges are politically motivated and amount to lawfare designed to assassinate Evo’s character. While it is certainly no coincidence that these allegations resurfaced after Evo organized the “Great March to Save Bolivia”, a weeklong march of thousands of protesters demanding the resignation of Arce’s cabinet, the evidence put forth so far is worrying.

The Bolivian right and several other social sectors have called for the government to declare a State of Exception and mandatory curfew while military forces clear the roads, however, the government has yet to authorize such a use of force.

Morales is not the unifier he once was

Although the regional roadblocks in Cochabamba created substantial tension, Evo had originally called for national blockades, which failed to manifest.

Evo is far from the nearly unanimous leader of indigenous people in Bolivia he once was, his popularity having slipped considerably in recent years. His organic support is almost entirely localized to campesino (rural poor) sectors in Cochabamba.

He is indisputably the king of Cochabamba, but the events of the past month show he is limited in his ability to mobilize people outside that region. On November 1 Evo suggested that his followers lift the blockades, as he was going to initiate a hunger strike demanding dialogue with Arce.

Some bases refused the suggestion and the blockades continue, albeit in reduced numbers.

Bolivia experienced similar blockades this year, organized in response to the growing economic crisis. The Tupak Katari Peasant Workers’ Federation of La Paz (I attended several meetings and marches), whose blockade staged a weeklong series of roadblocks in mid-September and demanded solutions and Arce’s resignation.

The Arce government’s response to these blockades was unprecedentedly harsh, with four union leaders being arrested and sentenced to 3 years in prison for their roles in blocking the road from El Alto to Copacabana.

In the Federation’s meetings at the time however, it was clear that criticism for Arce did not mean the organization supports Evo. “Neither with Arce nor with Evo and even worse with the right,” said one leader.

Although Evo constantly claims to represent the mass Indigenous movement in Bolivia and to be in general the leader of the Indigenous, peasants, and the poor, my experience in the Aymara highlands suggests he no longer can credibly claim to represent their organized sectors.

Criminal accusations against Evo amidst political infighting

The most detailed ongoing case against Evo is for statutory rape and human trafficking pertaining to a girl he allegedly met and initiated a relationship with while she was 15. As a result of this relationship, he is also accused of fathering a child with the victim. The child would be 8 years old today. After Tarija Attorney General Sandra Gutierrez denounced the crime and emitted an order of arrest for Evo Morales she was swiftly fired by then Attorney General of Bolivia Juan Lanchipa (he is no longer AG and she has since been restituted to her post).

After the coup in 2019, the interim Añéz regime investigated Morales for an alleged relationship with an (at the time) underage girl. There is some evidence that the woman in question accompanied Evo to his exile in Argentina in 2020.

There was later an attempted kidnapping of the alleged victim and her 8-year-old daughter from the daughter’s school, and the victim has presumably gone into hiding since. The alleged victim’s father was arrested for his supposed complicity in his daughter’s victimization and swore to police during questioning that his granddaughter’s father was Evo Morales.

In exchange for the alleged relationship with Morales, members of her family received government jobs and special legal treatment. According to a recent update in the investigation from Tarija Attorney-General Sandra Gutierrez, the alleged victim and her mother took no fewer than 79 domestic and international flights between 2015 and 2019, which would be impossible for a humble family in Tarija without a third party paying for it. According to Gutierrez the investigation already has 8 folders worth of material compiled.

Evo is also facing a criminal complaint in Argentina for allegedly living with underage girls brought from Bolivia during his period in exile. Angelica Ponce, who was in Evo’s inner circle at the time, has said that it was common knowledge at the time that Evo was living with underage girls in Argentina. The Argentinian government has formally accused Morales of sexual abuse and human trafficking.

The End of the Age of MAS?

The power struggle between Arce and Morales has been described as a “catastrophic stalemate” by Morales’s former VP Alvaro Garcia Linera, and illustrates deep schisms in Bolivian left that are unlikely to be resolved before the 2025 elections.

The Bolivian right and far-right have made some gestures towards uniting around a single candidacy to oppose MAS, and it would not be surprising if they managed to win. Manfred Reyes Villa, the current right-wing Mayor of Cochabamba, is arguably the right’s most well-positioned candidate.

Although the Bolivian military and police have a longstanding rivalry, they put their differences aside in the 2019 coup and could very well do so again. The right is already mobilizing a discourse that the Arce government is using the police as cannon fodder against violent terrorists.

Given the abortive military coup in June, a second more serious attempt is not an impossibility.

Beyond this, it seems necessary that the Arce government finish its disastrous term in office and that the investigations against Evo run their course. Evo will continue maneuvering to try and force his way back to the presidency for as long as he is able. Neither he nor Arce have much potential of winning a democratic election in 2025.

It seems that the decades-long age of total MAS dominance over Bolivian politics has ended, but it is not yet clear who will step into that vacuum.

We’re a day late in publishing this piece we know! Apologies for that. Late-breaking news in both Bolivia and Argentina affected edits in process considerably, and we thought it best to use the extra time to get everything right rather than rush out copy that would have been inaccurate only hours later. Thank you for you patience and for supporting indie media.

"In exchange for the alleged relationship with Morales, members of her family received government jobs and special legal treatment. According to a recent update in the investigation from Tarija Attorney-General Sandra Gutierrez, the alleged victim and her mother took no fewer than 79 domestic and international flights between 2015 and 2019, which would be impossible for a humble family in the Tropic of Cochabamba without a third party paying for it. According to Gutierrez the investigation already has 8 folders worth of material compiled."

Just a tiny correction:

The victim didn't live in the tropic of Cochabamba, she lived in Tarija