Ecuador’s indigenous peoples apparently haven’t forgiven left-wing violence against them

Right-wing candidate Noboa won presidential elections by double digits. Preliminary data seems to show he made gains in regions with large indigenous presence

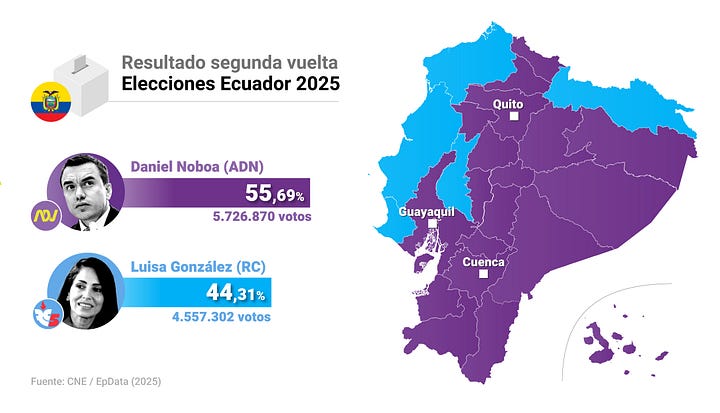

Right-wing incumbent Daniel Noboa has been officially declared the winner of the Presidential elections in Ecuador by a double-digit margin. This strong showing defied both polling leading up to the election and broke from the closeness of the first round, which was an effective tie with Correista candidate Luisa Gonzalez.

Gonzalez has said she will not recognize the election results without a recount and claimed that the voting process was marred by fraud. She did not provide evidence for her accusations.

Meanwhile, her political mentor Rafael Correa, currently in Belgium after corruption convictions, has supported the fraud allegations and called for supporters to take to the streets, even re-posting communiques on social media calling the elections a “coup”.

Yesterday afternoon, when Gonzalez made the fraud accusations, Ecuador’s National Election Commission (CNE) released a statement that observers had noted no serious irregularities as part of election processes.

A lot of media is focused on the hour-by-hour drama, but last night, after 13 hours of election coverage, we at PWS noticed a less-discussed but perhaps more relevant phenomenon.

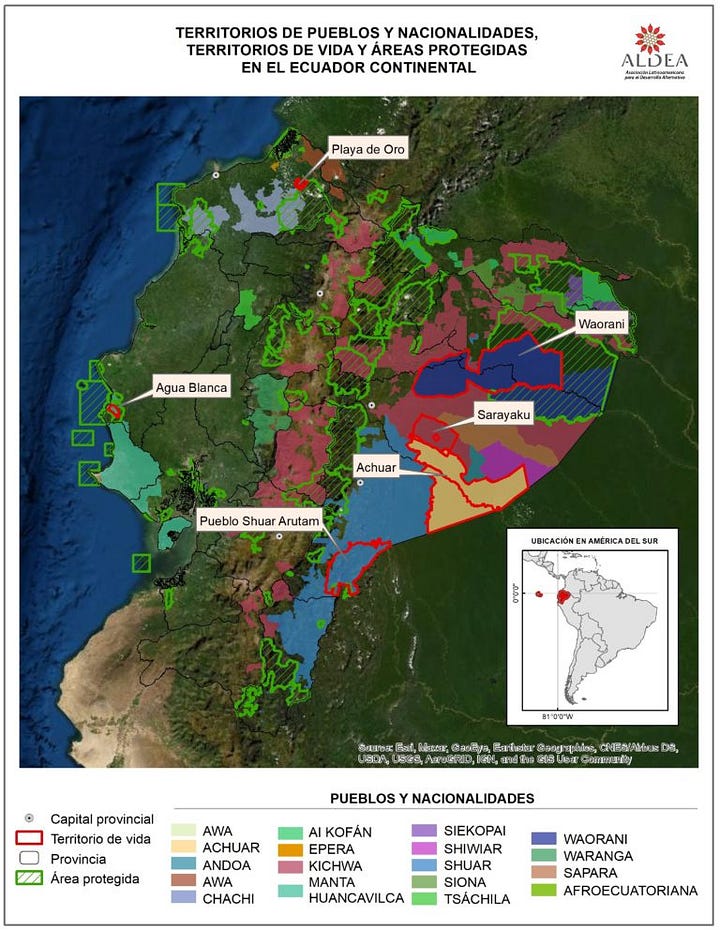

Although Gonzalez tried to court indigenous support, and even obtained the public support of Leonidas Iza, a leftist leader in the Pachakutik party, she seems to have failed to win a majority of support in the regions of the country where the indigenous populations are largest.

The endorsement by Iza was controversial within the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), the organization of which Iza serves as president. (Our piratical companions Douwe and Anastasia have an excellent long-form piece this week in Al Jazeera that breaks that dynamic down.)

Indigenous communities in Ecuador have long been anti-Correa after what they viewed as a “betrayal” by the divisive president during his time in office — when he actively pursued extractive policies on indigenous lands and persecuted environmental activists among those communities who opposed his policies.

She met with leaders of Pachakutik and swore to implement an agreement of 25 points into her campaign platform, but preliminary data strongly suggests her efforts were not enough.

As one journalist I spoke to who covers indigenous politics in Ecuador, who asked not to be named for fear of criticism from his newsroom, CONAIE “hates Noboa. But they hate Correísmo more.”

Gonzalez and Noboa both achieved roughly 44% of the vote in the first round of elections, leaving 12% seemingly up for grabs in round two. Iza, who ran as part of the PK party, garnered just over 5%, with the remaining votes split among a handful of candidates.

Both campaigns courted those votes, especially among indigenous communities, which have a relatively strong political presence in Ecuador. But Gonzalez received roughly the same percentage of votes in the second round (44%) as she did in the first, while Noboa expanded his lead to 55.6%.

Politics in Ecuador have long been a contest between Correísmo and other ideologies, and Correistas have long sidelined indigenous voices in that struggle.

This time, although certainly not the only factor in elections, that dismissal and, in the past, even outright persecution has come back to serve them yet another electoral defeat.