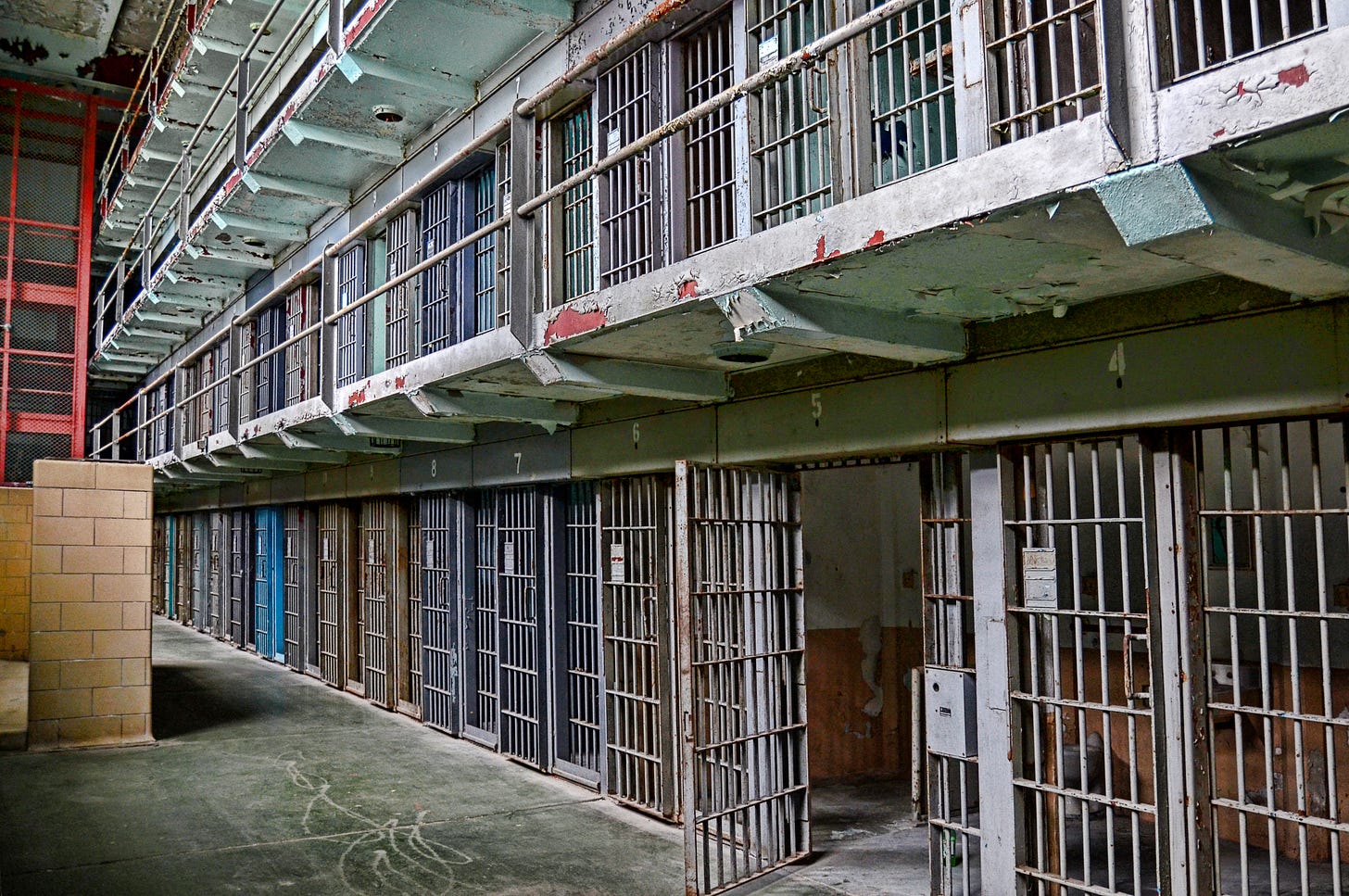

Ecuador’s prisons spiral toward violent collapse

The president has sent in the military and pardoned thousands

At the edge of Parque Vincente Leon in Latacunga, Ecuador, a group of teenagers were huddled around their phones, obviously transfixed but not laughing. A man walked past me, casually took out his phone, then seconds later stuffed it into his pocket, mouthing “Shit!”. My own phone buzzed.

It was a video of a man lying in a pool of his own blood, his severed head sitting on his chest. Then a flurry of messages and a call. “They took over the prison and are killing people. Go home. Go home now!” my friend told me. I could hear police sirens blaring and a military jeep had just pulled up next to the park.

On February 23, prison uprisings led to 79 deaths across three Ecuadorian prisons, including in Centro de Rehabilitación Social de Cotopaxi, just north of Latacunga. It was a coordinated assault as part of a power struggle between various gangs over control of the nation’s prison system. Prisoners used smuggled weapons to torture and kill rivals, broadcasting the assault live on social media. It was only the beginning of a wave of violence that would sweep Ecuadorian prisons in 2021, culminating in the deadliest prison uprising in the nation’s history.

In September, at least 118 were killed in the Litoral Penitentiary outside Guayaquil. Videos circulated of inmates armed with chainsaws and firearms dismembering their victims. On November 13 another riot killed 68 in the same prison.

Prison violence in Ecuador has spiraled over the last few years. In 2019, 19 prisoners were killed nationally, rising to 51 in 2020. In 2021, following the riots, that number has grown to over 300.

Due to “tough on crime” policies over the last two decades, prison populations have grown exponentially, as has the power of criminal groups inside jail walls. Incarceration rates have nearly quadrupled, from 64 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2000, to 220 in 2020, according to Quito-based watchdog, the Regional Foundation for Human Rights Counsel (INREDH).

But overcrowding isn’t the only cause. Prisons in Guatemala, for example, have higher overpopulation rates and lower murder rates. Widespread corruption among prison officials and the growing influence of Ecuadorian gangs battling for control over illicit economies within mega prisons have grown as well.

The prison system has been a long-neglected part of the justice system, and as populations grew, criminal networks became more sophisticated, eventually asserting control over the prisons they exist in.

José, 30, spent ten days in Centro de Rehabilitación Social de Cotopaxi in 2019. “Things have changed a lot since then,” he said. “Now everyone is scared of the prisons, and not just the criminals but even activists. If you get arrested at a protest or if you upset the wrong person you might wind up inside and you might get killed in there. You don’t even have to be guilty of anything.” Thirty-seven percent of those detained in Ecuador have yet to be convicted of any crime, either awaiting trial or held without charges.

In the November riot, gang members from multiple buildings converged on a building controlled by rivals. They used dynamite to blow holes in the wall and flooded in with machetes and guns. The building they attacked was a transitory facility and was primarily used to house inmates either awaiting trial or appealing their convictions. Among the dead were prisoners yet to be charged with any crime as well as human rights activist Víctor Guaillas, who was one of over a thousand protesters arrested during anti-government demonstrations in October 2019.

“I saw some people give bribes to the police while I was there, but it was small stuff. Mostly the police were in control,” José told PWS. “It’s changed now though. The prisoners are in charge.”

The country has officially been in a state of emergency since February because of the violence. President Guillermo Lasso also plans to pardon thousands of inmates to relieve overcrowding and has sent thousands of soldiers to prisons to restore order.

In addition to overcrowding, increased incarceration rates contribute to a jail population that comes disproportionately from poor communities, a trend that some scholars have argued criminalizes poverty.

Rising arrest numbers and increased minimum sentencing laws disproportionately affect vulnerable lower classes of society in Latin America, who are more likely to experience both wrongful arrests and false convictions than those with financial resources.

“There are strong social forces against reform,” said Gary Estrada, a human rights lawyer in Guatemala who studies incarceration in Latin America. “There is a cultural demand across all of Latin America to punish those accused of crimes that is sometimes stronger than the burden of proof involved in convicting them.

“A penal system- in theory- is supposed to protect the innocent as well as offer rehabilitation to the guilty, but this isn’t what is happening. What we have is a system that is almost purely punitive.”

* additional reporting by Joshua Collins

—

Stories We’re Watching:

Honduras's leftist presidential candidate Xiomara Castro was elected president this week, making history as the first woman to govern the Central American nation. The closely watched poll came four years after presidential elections marred by fraud claims and violence.

Buenos Aires is using its "blue dollar" exchange rate to attract digital nomads. The parallel rate means their income goes twice as far as under the formal exchange rate. Argentina is considering launching a digital nomad visa to draw high-earning remote workers and revive its ailing tourism industry.

Paraguay is experiencing a "monumental" child pregnancy crisis, a report by Amnesty International has found. Every day, two girls under the age of 14 give birth. In over 80% of reported abuse cases, the perpetrator is a family member or neighbour. But the country's ban under abortion under all circumstances except for threat to the pregnant person's life means that these girls cannot legally terminate their pregnancies, even though they are at substantially increased risk of complications and maternal death.

Spanish words of the week:

faena (f) - chore, labour. Nothing to do with hyenas.

contraloría - the comptroller's office. If you hadn't heard of this in English either, you're not alone. But this role, responsible for overseeing state or private accounting, crops up fairly frequently in corruption stories. Which is a relief, because we were secretly worried that it was the ideological position of being against parrots (loras), and as pirates, we're obviously against that.