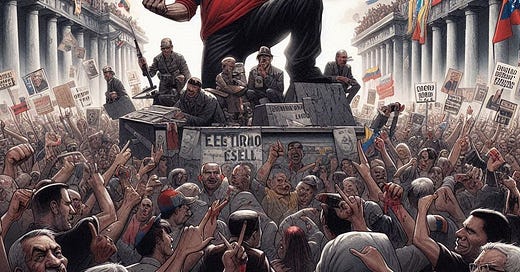

Elections in Venezuela are a genuine threat to Maduro: but that might not matter

Even longtime allies have abandoned him, but no matter what happens, Maduro is unlikely to simply walk away

Venezuela holds presidential elections on July 28. Opposition rallies across the country are packed, even in former Chavista strongholds, despite government attempts to make them as difficult as possible, such as arresting campaign workers, fining restaurants and hotels who provide services to candidates or their staff, and even closing roads to make the events as difficult as possible.

The airwaves are saturated with ads supporting the Maduro government, and the only mention of opposition candidates across the country are the President's attacks on them— claims they are undermining the “Bolivarian Revolution”, the leftist political revolution of Hugo Chávez that Maduro claims to represent.

But despite the obstacles, many within Venezuela are beginning to feel a sensation that they have not felt in years— that a real possibility for change may be just around the corner.

Polling is notoriously unreliable in Venezuela, due to unethical polling companies that often serve more as arms of political campaigns than neutral organizations, as well as self-censorship of voters themselves who may be reluctant to be honest about their political opinions in a country that has long oppressed or imprisoned dissidents— especially after a new “Anti-Hate Law” was passed in 2017 that allows for prison sentences of up to 20 years for those who speak out against the government.

But some polls show the current opposition presidential candidate, Edmundo González Urrutia. 30 to 50 points ahead of Maduro, despite the fact that before the current elections, few Venezuelans knew who has was— an expression of the amount of support Maduro has lost since the country was plunged into an economic and political crisis which resulted in nearly 8 million Venezuelans fleeing the country since 2014.

Even some of Maduro’s former political allies, such as the Venezuelan Communist Party, have also withdrawn their support and publicly announced they would back another candidate.

Urrutia took over the campaign after the two previous candidates were disqualified from running by the government. Right-wing candidate Maria Corina Machado won the opposition’s primary in October 2023 with 93% of the vote but was banned from running. As was her appointed successor Corina Yoris. She has since thrown her support fully behind González, holding rallies across the country calling for an end to the Maduro government.

Maduro, who took power after the death of Chávez in 2013, has held power for a decade and is seeking another 6-year term as president. Previous elections in the country were plagued with irregularities, and criticized by both the European Union and the Organization of American States in Latin America.

(Above: Video of Maria Corina Machado arriving to a campaign event on a motorcycle after police closed the highway, blocking the arrival of her motorcade)

Current elections were organized in response to the “Barbados Agreement”, which occurred in October 2023, between Maduro’s government and the opposition and mediated by representatives from Norway. Among other points, the accord stipulated that new Presidential elections would be organized by late 2024, and would include election observers from the European Union. Although the United States was not a direct party to the negotiations, they scaled back some oil sanctions on Venezuela as an incentive to stick to the agreement.

Venezuela has since uninvited EU election observers as well as broken promises not to arrest members of opposition political parties.

It is impossible to predict what will happen after the elections, but in the case of an opposition victory, it is quite possible that Maduro will refuse to step down— and his administration has a host of tools at its disposal to avoid doing so.

“I think the administration of Maduro is facing a tough choice,” Tony Frangie Mawad, a journalist in Caracas told PWS. “They could choose to impose a full transition from an autocracy to a Nicaragua-style dictatorship crackdown,” to prevent a loss. Or “they could try further indirect election influence, or even canceling the elections,” he continued.

Ultimately though, Mawad doesn’t believe Maduro is likely to simply step aside. Some analysts have suggested that unprecedented support could strongly weaken his support among allies, or inspire widespread protests in the streets.

But Maduro has been underestimated by political analysts, both domestic and international, before.

Some Venezuelans have described their feelings about the elections as “a see-saw between hope and fear”.

Leftist leaders in the region have also pressured Maduro to respect election results. President Lula, in Brazil, has on multiple occasions called on the Venezuelan government to fulfill their obligations under the Barbados Agreement. Petro, in Colombia, has announced that the country will not send election observers for a host of reasons, among them that Colombia “does not want to give the appearance of legitimizing elections.”

In the same statement, Colombia repeated previous calls for the U.S. to end sanctions against Venezuela. Boric, in Chile, has often criticized Venezuela’s human rights record and called for truly free elections in the country.

Both the United Nations and Human Rights Watch have criticized increasingly authoritarian crackdowns by the Venezuelan government ahead of elections. Meanwhile, the Maduro campaign has swung into full action.

Members of his party are organizing voter organization drives, pledging to ensure that every member will ensure that at least 10 friends and relatives likely to vote for Maduro make it to the polls.

The government has also staged rallies in Caracas, and invited journalists and influencers sympathetic to the government to come to the country ahead of elections, which Maduro has framed as a defense of the Bolivarian Revolution and a “struggle against Imperialism”.

Meanwhile, most of those Venezuelans living abroad will be excluded from casting a ballot, both due to onerous restrictions about foreign residents voting, and a lack of government infrastructure where the majority of them live.

Venezuelan embassies in the United States and Colombia were closed years ago, leaving many in the diaspora disenfranchised. Nonetheless, some of them are hopeful. Javier Guerrero, a Venezuelan artist in Medellin, when asked about his feelings on elections, replied “I don’t know what is going to happen. But this is the first time I’ve seen some Colectivos (social organizations created by Chávez, some of which act as informal militia), abandoning him.”

“This is the first time I see doubt from some of his traditional supporters,” he continued. Guerrero, however, stopped short of predicting an outcome. “Venezuela has proven over and over that it is anything but predictable. I just hope that if Maduro does finally leave office, something I personally hope to see in my lifetime, that we don’t just swing immediately to the far-right in a reactionary manner as a result.”

The Big Headlines in LATAM

As of Saturday evening, even Latin American news sites were dominated by the news of the assassination attempt of U.S. Presidential candidate Donald Trump. The fledgling democracy, which in recent years has been plagued by political instability and coup attempts, suffered another blow as one of its two octogenarian candidates from the elite upper classes was wounded when a shooter fired at him during a campaign event.

Most political analysts from the capital, called Washington D.C., were quick to call for an end to violence. Some international observers, however, questioned whether events such as this may be “the new normal.”

Many leaders from more civilized countries, in Latin America, offered messages of support for the ex-reality T.V. star turned ex-president, and condemned the assassination attempt.

There was no immediate news on whether a U.N-led peacekeeping mission would be deployed until order can be restored.

Ha! Sorry, we’re being a bit tongue-in-cheek here. We thought it might be funny to cover U.S. events in the tone many international media companies cover our own beats here in LATAM.

In other news, Colombia squares off against Argentina today in the semi-finals of the American Cup. This, sadly, pits PWS members against PWS members. But we promise to be civilized about it no matter who wins.

Spanish Word of the Week

Enchufados

An enchufado, in Venezuelan slang, is someone who has an enchufe, a source of power. The simplest translation to English might be “someone who is plugged in”. Corruption in Venezuela is endemic. Transparency International rates it at 177th out of 180 countries in the world.

Those who benefit from that corruption, or their family members, are often called enchufados. An entire Enchufado culture has emerged in Caracas in recent years, with young influencers with powerful family members posting images of their lavish lifestyles on social media, and driving demand for luxury goods, even as millions suffer from extreme economic crisis.

No matter what happens in the upcoming Venezuelan elections, the Enchufados are unlikely to fade from power anytime soon. Corruption is historically extremely resilient to regime-change.