Feminists on the move in Bogotá

Colombianas push back against a lack of progress on femicides, state capture of social movements, and silence in response to activists

This week’s feature in by Bogota based journalist Gabriela Herrera Gómez, and produced in conjunction with Ojala magazine, a feminist media company in Mexico City.

This year’s International Women’s Day march in Bogotá began in a distinct spot, at the intersection where Calle 45 crosses one of the city's most important avenues. Feminists gathered there beside a large mural in which yellow letters spell out the phrase “Las Cuchas are right,” using a slang term for “old ladies” that can be either affectionate or derogatory, depending on the context. Las Cuchas are a group of mothers from Medellín’s Comuna 13 whose children were disappeared. For more than 20 years, insisted paramilitary groups and state agents had dumped their children’s bodies in an abandoned landfill.

Finally, after years of excavations led by volunteers and the Unit for the Search of Disappeared Persons, human remains were found on December 18, 2024, just as Las Cuchas had claimed. The phrase “Las Cuchas are right” turned into a rallying cry that spread across the country. Movement organizations began painting it in murals, and they became a flashpoint for conflicts with the far-right, who tried to paint them over. The mural at Calle 45, which is emblematic of the dispute, became a space for discussion and debate on state violence in Colombia. That’s why organizers decided that this year’s march should start there.

Before the march began, members of the Domestic Workers Union, the Until they are Found Foundation and Mothers of False Positives (MAFAPO) gathered to share their experiences resisting forced disappearance and pushing the country’s historical debts to working mothers onto the agenda.

“Mothers of Medellín, you are not alone,” said Ana Páez of MAFAPO in a speech. “They called us crazy. Well, the crazy ones were telling the truth! Las Cuchas were right.”

Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) states that more than 110,000 people have been forcibly disappeared in the country since the armed conflict started in the 1960s up to the signing of the peace agreement in 2016. Authorities registered 1,730 new cases since July 31, 2016.

For the We are one Face Collective (SURC), which organizes Bogotá’s main 8M march, linking up with the Cuchas was a way to embrace and recognize their work. “State actors have been complicit in forced disappearances and other crimes,” said Laura Vázquez, one of the organization’s leaders. “This country still has a long way to go in terms of acknowledging that fact, but we can build historical memory through mobilization.”

Feminist resistance against fascism

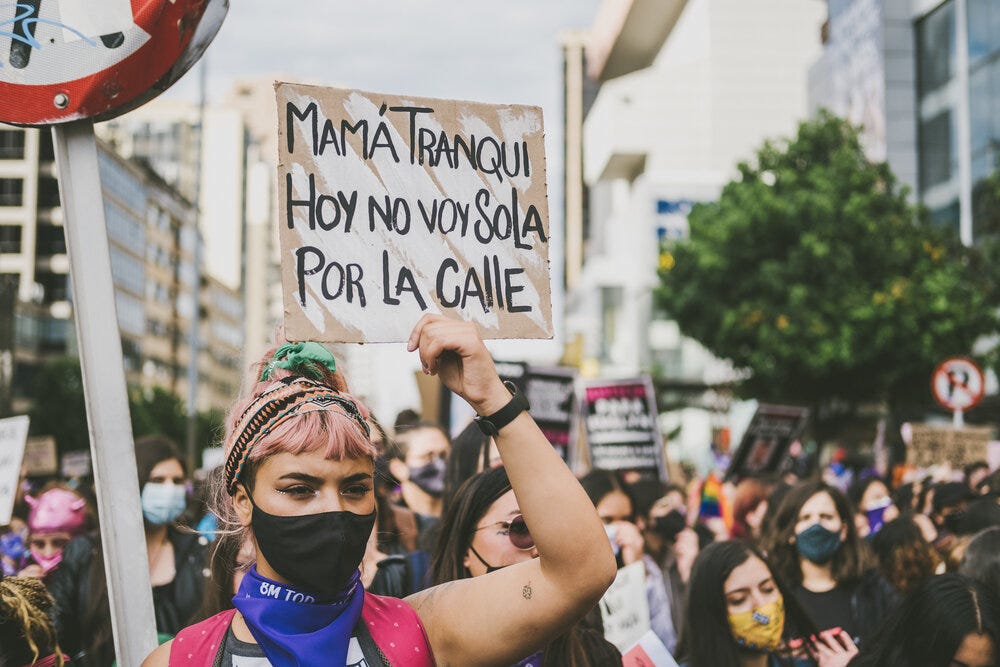

Starting at the mural, more than 8,000 women marched toward Carrera Séptima. They shouted slogans protesting the growing number of femicides in Colombia and spray painted walls with messages like “No more Galán,” which refers to Bogotá’s mayor, Carlos Galán.

I spoke with Daniela Silva, one of the coordinators of the People First School of Political Leadership, near the start of the march. Her group fights for women’s participation in politics, and one of her principal concerns is what she describes as the spread of fascism.

“Today we’re talking about women's rights, which gets us to reflect on the fact that there can be no equity without economic justice, but all of this happens under the threat of the advance of the right-wing in Latin America and widespread violations of women's rights,” Silva said. “The policies of the United States lead to violations of our sovereignty and also of the rights of migrant women, who are often victims of human traffickers and sexual violence.”

Heidy Sánchez, a Bogotá city councillor for the Patriotic Union party, expressed concern about this year’s elections in Colombia, which could feature women at the head of right-wing parties.

She highlighted the rising power of women-led far-right parties globally, including Giorgia Meloni in Italy and Alice Weidel of the German far right. “How will the feminist movement respond to this?” she asked.

With SURC members at the front, the march worked its way through the streets to a chorus of “All of Latin America will be feminist.” Vázquez said the slogan for this year's march is “feminist expansion and collective resistance,” which was selected with the changing global context in mind.

“Yes, there has been progress; yes, there have been achievements,” she said in an interview. ”The progress we’ve made has been hard won.”

The emergency of misogynist violence

Colombian women are on high alert. Seventy-nine femicides were recorded in the first two months of 2025. This is 50 percent more than what occurred in the same period in 2024 and that year had the highest number in six years.

March 8 began as news of two more femicides broke. Paola Rivera, a 28-year-old woman, was murdered by her partner in Puerto Boyacá. And Sharit Ciro, 19, an art student, was found dead near the city of Ibagué after leaving home for a job interview. Her family had reported her missing the previous day.

Feminists were furious and flooded the country’s main cities in a spirit of outrage but also of hope. From the Feminist Gathering in Cali and the Abolitionist Feminist Network in Medellín to the Chinas Berriondas Collective in Duitama and the Popular Mobilization Platform in Cúcuta and beyond, they took to the streets with signs bearing the names of their attackers, photos of victims like Paola and Sharit, and messages of sisterhood. “We owe it to those who never came back,” read a sign. One said, “The State protects my abuser.” And another read, “I’m marching because I am alive but I don't know for how long.”

They also directed the demand to end violence against women at police forces and the Bogotá city council, which has failed to provide effective protection. During last year's march, police attacked protesters, sprayed tear gas and cut off power to Plaza de Bolívar, where the march ended. Formal complaints and protests led to round-table discussions between feminists and district authorities, but SURC activists state that there has been no progress in efforts to get to the bottom of what happened.

Roughly the same amount of women marched this year as compared to the last, but anger at national and local government’s failure to protect the right to mobilize was distinct.

“We have a complicated relationship with local authorities,” said Carolina Peña, a member of SURC. “After we denounced the [police] violence, they held a few round table discussions but there has been no repair, no recognition, or a total lack of transparency about what occurred.”

Criticisms of the government

“There’s a lack of political support for feminist causes,” said Silva, of the People First School of Political Leadership. “As feminists, we have to talk about the national government’s unfulfilled promises.”

She was referring to the case of the Ministry of Equality, one of President Gustavo Petro’s flagship initiatives, which has been criticized for inaction under the leadership of Vice President Francia Márquez. It had only spent 2.4 percent of its budget as of December 2024.

The appointment of Armando Benedetti, the president's right-hand man, as interior minister was also top of mind among marchers. Adelina Guerrero Covo, his wife, has accused him of gender-based violence. “It’s atrocious that Benedetti received a senior government position after these accusations,” said Edna Robles, from the Teachers' Trade Union Movement.

Other women lauded the appointment of members of previously excluded populations, like Indigenous peoples, Afro-Colombians and trans people, to government offices. Some believe that the failures of Petro's government are the result of structural conditions that cannot be fixed in four years.

The march came to an end in the square in front of the Bogotá City Council amid drumming, performances and a spirit of rage. Some militants surrounded the statue of Luis Carlos Galán, the current mayor’s father and an iconic figure who was assassinated in 1989. They painted the statue with green, pink and purple colors and built a bonfire at its base.

The following morning images of the posters at the foot of the statue inundated the news. “Not one more, we want to be free,” read one sign. “Protect us like you protect the monuments,” read another.

Gabriela Herrera Gómez is a Colombian cultural journalist focusing on gender issues, human rights and literature.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Argentine pensioners have been staging weekly protests against President Javier’ Milei’s austerity programs in Buenos Aires for months. This week, football fans joined them to support their cause. Police responded forcefully, with rubber bullets and riot squads, even teargassing and beating retirees in the street.

Protesters burned a police car in the ensuing melee and over 150 people were arrested. More than 200 protesters were injured, including photojournalist Pablo Grillo, who was hit in the head by a teargas canister, and remains still in critical condition.

Milei, in the days that followed, promised “iron hand” crackdowns on future protests. The U.N has called for an investigation into the violent actions of security forces.

A citizen investigative group in Jalisco, Mexico discovered a mass grave and the remains of hundreds of people, at a ranch the government says was used as a crematorium by cartels.

The nonprofit search group Warrior Searchers of Jalisco discovered the site on March 5. Mexican authorities confirmed their discovery on March 10, promising a full investigation.

The citizen group documented personal items belonging to hundreds of people, including over 400 pairs of shoes. The Women who run the organization also alleged that in addition to disappearing people, criminals who ran the compound engaged in organ trafficking.

Spanish Word of the Week

A otro perro con ese hueso - “take that bone to another dog”

In Colombia, if someone tells you a tall tale you might respond with the above phrase as way of telling them you don’t believe their lie.

Example: A otro perro con ese hueso, sé que no fuiste al gimnasio —Don’t try to fool me, I know you didn’t go to the gym.

This is a phrase we often think here at PWS when we watch politicians give speeches. Fortunately for them, however, it seems that there are always a few dogs happy to accept any bone they can get, and a few voters who will support some politicians no matter what they do.