Five years after Colombia signed its peace deal, armed groups are thriving

Meet the narcos, guerillas and paramilitary forces battling for control of the country’s criminal world

As I wrote at my desk September 21, 2019, near Villa Rosario, on the Colombian-Venezuelan border, I heard a loud explosion. Confused, I grabbed my camera, rushed down the road and arrived at the scene of a small restaurant bombing. Medical personnel hadn’t yet arrived. Injured and bloody lunch-goers milled about as bystanders shouted and tried to help. One man being helped into the bed of a nearby truck had lost his leg from the knee down.

A younger man sat amidst scattered and broken tables, clutching his head, blood running between his fingers. “What happened here?,” I asked onlookers.

“Someone threw a grenade,” a woman told me. The restaurant owner hadn’t been paying the vacuna [protection money] to the right side. Or maybe he had been paying it to the wrong one. My editors didn’t care when I pitched the story. Scenes like this play out constantly across the country— it was just another day of “peace” in Colombia.

The grenade attack was part of a war that raged from 2019 to 2020 between leftist rebel group the National Liberation Army (ELN) and right-ring paramilitary group the Rastrojos near Cúcuta, Colombia over control of lucrative smuggling territory. I lived in the region during that period, and saw firsthand how a promised peace never arrived.

Colombia is celebrating the 5-year anniversary of the signing of its historic peace accord. The deal ended, at least in theory, the longest-running civil war in the Americas. For more than five decades, leftist guerrilla group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) engaged in open warfare with the national government and their paramilitary allies.

The deal was supposed to put an end to fighting, invest in long neglected rural areas and usher in economic opportunities for communities that had been caught in the crossfire.

None of that has happened. Rather, armed groups from both sides of the civil war have splintered and fractured as they stepped into the vacuum left when FARC fighters disarmed. They are growing rapidly again and insecurity in rural areas is increasing.

Signed on November 24th, 2016, Colombia’s peace deal was almost scuttled before it began. The measure failed a popular referendum by less than one-percent. Then president, Juan Manuel Santos, submitted it to Congress instead, where it narrowly passed.

Since then, progress for the imperfect deal has been slow as armed groups scramble to fill the gap left by FARC. Cocaine production is at an all-time high, violence is increasing in the areas where they clash, and the killing of social leaders, human rights defenders and signatories of the peace deal are rising.

The reach of these groups goes much deeper than the illegal economic activities that support them. They act as the de facto government in many of the regions where they operate, imposing their own law, sometimes in collaboration with politicians and police.

Who are these groups that wage war in the shadows of peace?

Meet the Paracos

Colombia's "self-defense forces" grew from citizen groups and landholder militias into more organized, criminal groups in the early 1980s, when drug dealers facing attacks and kidnappings from rebel forces created MAS (Death to kidnappers, by its Spanish initials), and the later formation of los PEPES (People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar), to aid the government fight against the Medellin cartel in the 90’s.

The largest coalition of these groups was the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). These right wing death squads used the conflict as an excuse to build an empire of narcotrafficking, extortion, kidnapping and territorial expansion. At the height of their power they operated in two-thirds of the country and boasted nearly 30,000 soldiers.

AUC disbanded, but much of the leadership formed new paraco groups, hundreds more of which have spawned in the years since.

These forces are known as “paracos”, short for “Colombian paramilitaries”. And as they tapped into the drug trade amidst the country’s civil war, their numbers and territory expanded rapidly. In 2006, many disarmed as part of a deal with the administration of Álvaro Uribe, but others simply formed new groups which have grown exponentially in recent years. Paracos were active in 291 municipalities in 2020, up from just 30 in 2019, according to the Colombian police.

The largest of these today has many names: the Clan de Golfo, also known as AGC and the Urabeños, have become the most powerful armed group in the country.

Since their founding by ex-AUC leaders, the group has absorbed or established informal ties to hundreds of independent narco paramilitary cells, and has links to politicians and security forces, especially in their home turf of northwest Colombia. The Medellín prosecutors office was accused of cooperation with AGC in 2013. A police colonel from Barranquilla was arrested for being on their payroll in November and the Char family on the northern coast, which is deeply tied into the politics in AGC territory, have survived dozens of accusations of financial ties and money laundering with the group.

They wage a multi-front war against FARC splinter groups which abandoned the peace process, ELN guerillas and other non-politically aligned narcos for control over territory and illicit activities. Most recently, they forged an alliance with the Rastrojos, who were nearly eradicated by their year-and-a-half war with ELN in Norte de Santander.

Welcome to Guerilla Country

Over 90% of FARC combatants laid down their arms and joined civil society as part of the peace. But some FARC battalions rejected the deal, forming “post-FARC” or “dissident” groups that have resumed recruitment. These dissident groups expanded in 2019 when some FARC leaders who had agreed to the peace deal became convinced the government would never fulfill its promises and returned to the jungle.

Although they control far less territory than they did before the disarmament, they are still believed to control over 5000 fighters.

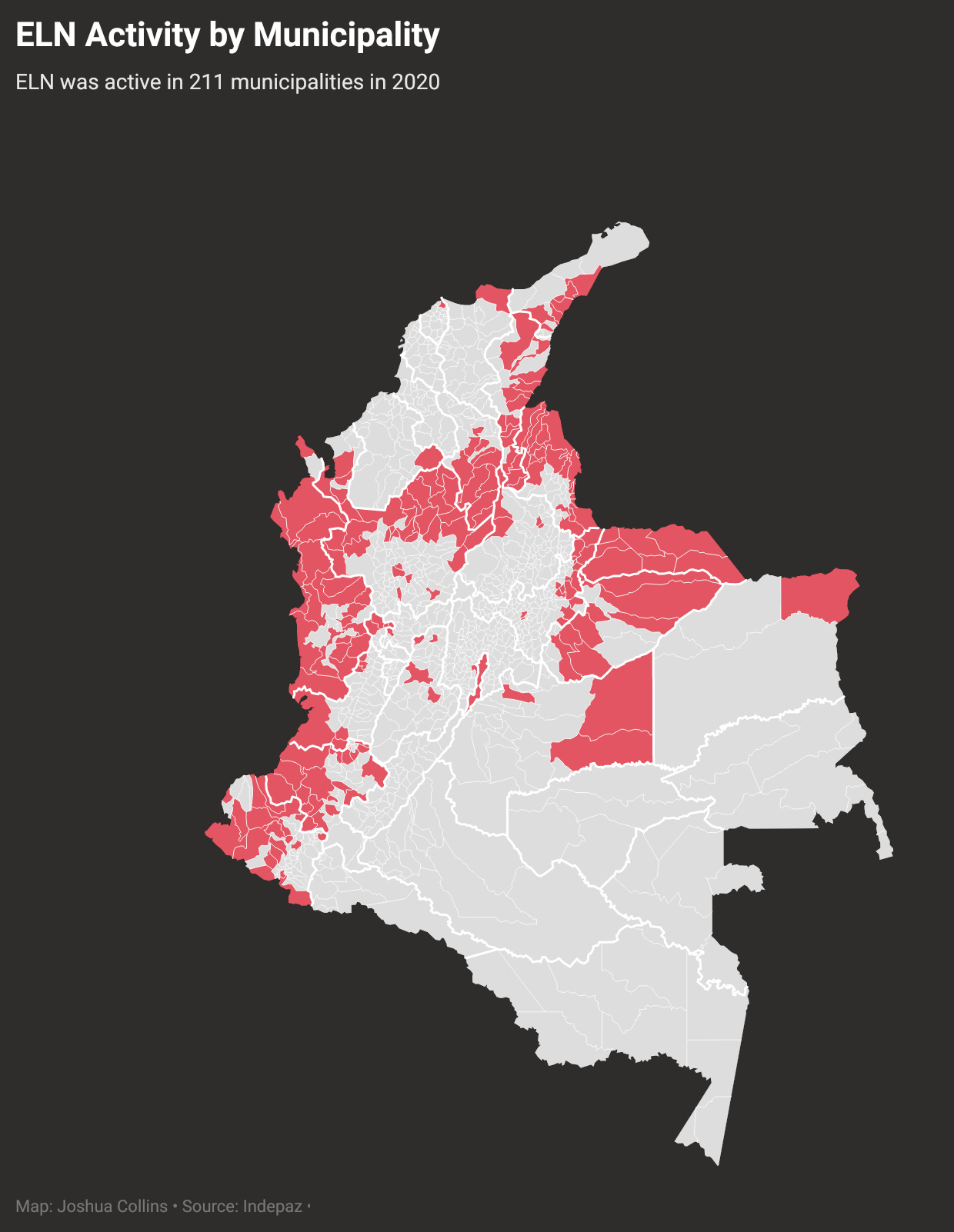

Other guerilla groups however, have grown rapidly, especially leftist ELN, which rejected the 2016 deal. ELN activity rose from 136 municipalities in 2018 to 211 in 2020. Originally founded by Marxist-Leninist priests in the 1960s, the ELN steadily lost ground to paramilitaries during the war. The government attempted peace negotiations with the ELN in 2002 and again in 2018, but the outreach was shattered when ELN bombed a police station in Bogotá that same year, killing 21 people.

As a result, confrontations between ELN and the government have escalated. Since the accord, they have moved swiftly into territory abandoned by former FARC fighters despite killings of high level commanders by the government.

And the peace?

Public support has increased for implementation of the peace, with 74% believing it is “the best strategy for dealing with the conflict”, but most of the goals set forth by the government have not been met and the current administration’s record suggests Duque prefers military solutions to civil ones.

In addition to the military incursions into rebel territories and the never ending War on Drugs, the Colombian government has conducted 36 aerial bombings of guerilla encampments since Duque took office in 2018, killing 22 minors. Defense Minister Diego Molano has defended the actions as necessary, claiming that the children were being indoctrinated as “machines of war”.

The government also recently arrested the leader, AGC, Dario “Otoniel” Usuga, stating at the time that the leadership loss would be a death blow for the Clan de Golfo, but the group's activities have continued unchecked. Military solutions haven’t resolved the core causes of conflict.

David Restrepo, environmental director for the Center of Security and Drug Studies at the University of the Andes, said in a phone call, “These are the same regressive tactics the government has tried for decades. They didn’t work then and they are unlikely to work now.”

“Coercion alone cannot establish bonds of trust between the state and local citizens,” wrote International Crisis Group in a report from 2017 that proved eerily prescient, “Instead, they need to be persuaded [by the government] that there is a better alternative.”

Stories we’re watching:

On Saturday El Salvador’s President, Nayib Bukele, announced a $1 billion ‘volcano bond’ to be issued in 2022. Half of the bond will buy Bitcoin with the remaining $500 million used to develop geo-thermal power at the base of a volcano in order to mine the crypto-currency. If successful it may herald an alternative method for nation states to raise debt, by tying the development of excess energy--such as hydro in Paraguay--to Bitcoin mining.

Honduras is holding general elections on Sunday, and the country is braced for trouble. In 2017, current president Juan Orlando Hernández was re-elected amid widespread accusations of electoral fraud, and the subsequent protests resulted in a bloody crackdown. Hernández is accused of high-level involvement in the drug trade. Jared Olson wrote a thread on what's at stake

thank you for the background