Former Guerillas Seek Peace Through Beer

A growing number of demobilized communist rebels have recently turned to a more civilian pursuit: brewing craft beer. Now they hope a divided country can come together over a pint of pilsner

Hola piratas-

This week’s piece originally appeared at OZY media, but that media company is now defunct, their website dead, and their editors unresponsive. We were sad that it no longer lives anywhere on the internet as it is one of our favorite positive cultural stories we have done on Colombia, so we updated it and brought it here, where it can live on forever at the Good Ship Capybara.

Read the story of Guerilla Brew: and if OZY wants to sue us for posting our own work, well we guess they can try, but we also doubt they can afford the lawyers.

Former Guerillas Seek Peace Through Beer

A growing number of demobilized communist rebels have recently turned to a more civilian pursuit: brewing craft beer. Now they hope Colombia’s first leftist president can create the conditions for a divided country to come together over a pint of pilsner, before the faltering peace accords leave everyone with a bitter taste in their mouths.

Bogotá, Colombia—For 12 years, Alexander Monroy waged war against the government as a member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). Now he brews beer in an effort to ferment peace in a country whose scars have never fully healed.

“Colombia loves beer,” he says, laughing over a drink in the Peace House, the cultural center where his brewery operates. “What better way to show people the possibilities that peace can bring?”

Monroy is part of a collective of ex-guerillas that brew “Trocha” beer in one of many breweries started by former rebels in recent years. Groups like his are hopeful that Colombia’s first leftist president, Gustavo Petro, a former guerilla, will bring an end to a cycle of rising violence in the rural countryside and years of broken promises by conservative governments.

“Three-hundred and twenty-five of us have been murdered since the peace accords,” he says, referring to the number of signatories to the 2017 peace treaty who have been killed since the FARC rebels agreed to lay down their weapons for the promise of safe passage back to civil society. “Security is something we have to think about constantly.”

Beer is helping that process. Monroy says the Bogotá neighborhood has largely embraced his guerrilla brewery. While most of the clients throwing down pints identify as leftist or socialist, Monroy says The Peace House opens its doors to Colombians of all political stripes. It’s a notable new openness in a country that is accustomed to settling its differences with bullets.

“The peace has allowed spaces like this to flourish,” says Monroy, as he surveys the mostly young crowd of people laughing, dancing, or arguing politics. “There has been a growing awareness in Colombian society that we [former guerrillas] are not the evil monsters the government claims.”

A long road to peace

The peace accord hatched five years ago between FARC fighters and the government brought an official end to a civil war that raged for 53 years. Thousands of rebels agreed to turn over their weapons and reintegrate into Colombian society. In return, the government promised to invest in long-neglected conflict zones, implement land restitution to some of the more than 8 million persons displaced by the conflict, and create economic alternatives to the informal or black market activities that sustained so many of the war-torn communities.

But the government didn’t keep its end of the bargain. Instead, outgoing President Iván Duque, who won election in 2018 on promises to dismantle aspects of the peace deal, resorted to aggressive military campaigns against other armed groups, launching violent offensives that some have likened to massacres, including the bombing of children.

The result of sputtering peace has been the rearmament of rebel organizations and drug cartels in a lawless and abandoned countryside, and growing social unrest in the cities, capped by a massive nationwide protest last summer that claimed 60 lives. Such conditions set the stage for the leftwing opposition to win June’s elections, which were essentially a referendum on the conservative political establishment.

President Petro entered office on August 7 on promises to fully re-implement the 2017 peace accords and open new negotiations with armed groups that weren’t party to the original deal. “Without peace, there can be no democracy,” he said.

As part of promised military reforms, Petro has appointed Ivan Velasquez, a former UN corruption investigator and assistant magistrate to the Supreme Court, as his incoming Minister of Defense. Velasquez has a history of investigating the ties between criminal groups and the Colombian government. He also plans to reorganize the structure of state security forces, placing the national police — currently under the command of military leadership — under civilian control.

Make beer, not war!

The collective at “La Trocha” is not alone. A growing number of ex-guerillas trying to reincorporate into society have found new callings in the ambrosial craft of artisanal beer.

Carlos Alberto Grajales was a FARC fighter for 12 years in Nariño, a hotspot of the civil war in southwestern Colombia. He then served a dozen years in prison on charges related to his actions as a rebel.

After his release from prison, he rejoined the FARC as a political activist before signing the peace deal and officially demobilizing. He feels the peace plan as it exists today was not the deal he signed in 2017.

“There hasn’t been support from the government,” he says. “They tell people in conflict zones to grow coffee or potatoes, but there’s no market for that.”

There is, however, always a market for beer.

So Grajales turned to brewing. He and 17 other former guerillas pooled their resources, which amounted to about $100, and began brewing what they call “La Roja” beer.

“We make a red pale ale,” he says with pride. “The name reflects our past and our ideology, one of communism.”

He and his partners reinvested the earnings from their first sales and have since grown into a fully certified brewery that boasts national distribution as well as their own “cervecería” — a capitalist endeavor with some communist trappings.

“They wanted to delegitimize and demonize us,” he says of the outgoing right-wing government. “They only wanted to talk about the crimes of the guerrillas, and never the atrocities committed by police and the military.”

He believes the peace process, however flawed in its implementation, is finally allowing for a more complete story to emerge.

“The truth about crimes against humanity and grave human rights violations committed by the government and their [paramilitary] allies is coming to light, thanks to the peace deal.”

The peace deal has also brought more democracy, as messy as it is.

“Mass protests as we have seen in recent years could never have happened during the war,” Grajales says. “The military would have claimed everyone in the streets was a guerilla and crushed them mercilessly.”

Whether President Petro can implement the unfinished promises of peace remains to be seen, but for the former fighters gathered around the bar, they’re happier holding beers than guns.

As Grajales says, “The only other option is more war, and we have wasted far too much time as a nation on that path.”

The Big Headlines in LATAM

A case of four indigenous children, lost in the jungles of Colombia since their plane crashed on May 1 has captured public attention here. But rescue teams at the search site say that small footprints, as well as discarded fruit and baby formula at the crash site suggest the four siblings, who range in age between 11 months and 13 years, likely survived.

Since last week, more discarded items from the children have been found, as 100’s of soldiers comb the dense jungle for signs of the children. This week, nearly a thousand indigenous volunteers joined the search efforts to locate the children, who are believed to have been wandering the jungle for nearly a month.

What we’re writing

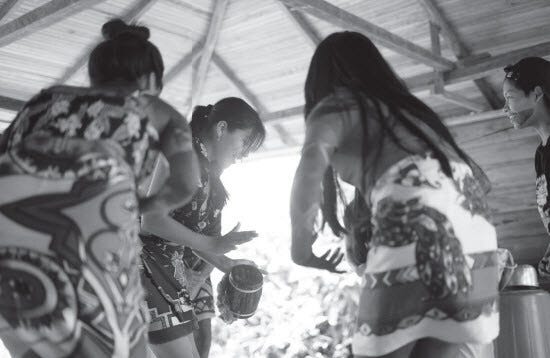

Joshua and Daniela are honored to be included in NACLA’s Summer edition: Amazonia on the Brink. We did a story on the young Emberá indigenous women who practice cultural preservation as an act of resistance. Meet “Nepono Werara”.

The journal exists principally physically, but if you would like to read the story of Usy, who runs the cultural organization, which offers a safe space for displaced young Emberá women in Chocó, drop us an email. We’re happy to send over a PDF.

What we’re reading

Ioan Grillo, in his newsletter “Narco Politics” wrote this week about Pirates in Mexico. Yes, that’s right, pirates. We were of course thrilled— until we learned they have all disappeared. That made us sad. But it’s a fascinating story!

Spanish Word of the Week

This week’s word is more of a phrase: echar un visto gordo

The literal translation is “to toss a fat glance”, but the closest approximation in English would be “turn a blind eye”— to ignore misdeeds or illegal activities instead of drawing attention to them.

This is what we hope a former editor at OZY, who we know reads our newsletter, does in regards to this week’s piece. But, hey, what are pirates really after all if not masters of their own destiny— and labor?

We would argue they aren’t pirates at all.

As always, hasta pronto piratas!

Hell yeah for being pirates - and anyway, this story is too lovely not to be shared far and wide! 💜