Gentrification Spurs Cocaine Surge in Medellín

An influx of digital nomads and ex-pats aren't just driving up rents, they're stimulating the city's black markets as well

This week’s feature is by Colombian journalist Nicolás Zuluaga

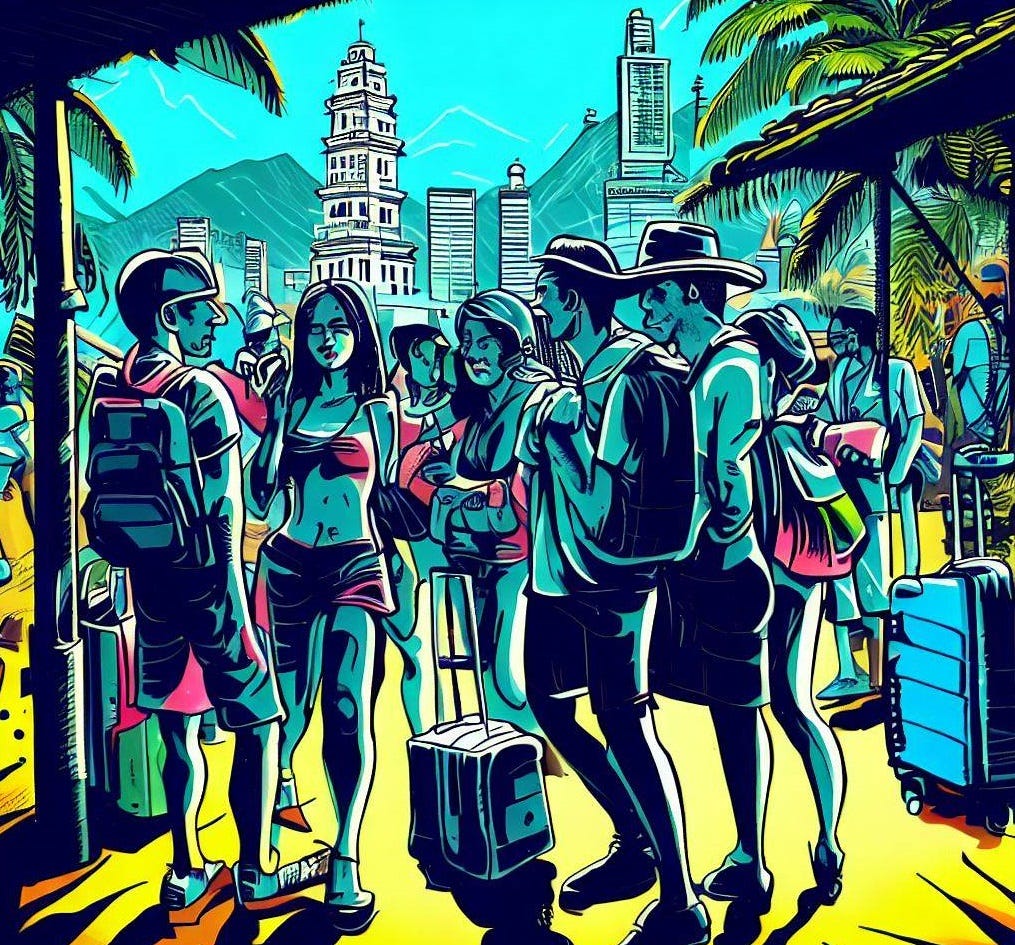

In the last decade, Medellín has undergone a significant rebirth, becoming safer, more prosperous, and notably tourist-friendly— earning international recognition as an emerging destination for those looking to live or work abroad.

As the stereotypical images of cartels fade into the past and the scars of the country’s 53-year civil war begin to heal, the city has been the subject of countless articles describing the “Medellin Miracle”, citing reduced crime and increased economic growth. However, those articles often neglect to address the new underlying drug dynamics in the city brought about by the influx of tourists.

Even as Medellín distances itself from its traumatic past, the city faces a new surge in cocaine consumption, not in spite of its new emerging positive identity, but at least partly because of it.

New residents and a booming domestic cocaine business

The influx of digital nomads and transient tourists to Medellín has sparked debates about gentrification as land-owners hike prices, leaving some residents frustrated with rising costs of rent and consumer goods alike. Black markets haven’t been immune to the phenomenon either. As Medellin’s new visitors flock to neighborhoods famous for their nightlife, cocaine prices have sky-rocketed as well.

In turn, this translates to Medellin having significantly higher cocaine consumption levels than the capital city of Colombia, Bogotá. The monthly minimum wage is COP 1,300,606.00, which is approximately equivalent to $325 USD. Recent government statistics show that "15.7% of the total employed workforce in Colombia earn the minimum wage, but most importantly, the figures reveal that 43.1% of workers in Colombia earn less”.

Foreigners arriving in Medellín often possess higher purchasing power than local residents, and they are willing to pay more for illicit substances. As the number of foreigners grows in Medellín, demand for cocaine has increased.

In Medellín, a gram of cocaine in working-class neighborhoods such as Barrio Antioquia, Trinidad, sells for as little as COP 10,000 ($2.50 USD), up to COP 100,000 ($25.00 USD) depending on quality and purity.

Many dealers also spoke of designer drug “2cb”, Tusi, or “pink cocaine”, though Tusi isn’t actually cocaine, is quickly growing in popularity and a gram can cost up to COP 200,000 ($50.00 USD).

But prices can go extraordinarily high in exclusive and tourist sectors such as El Poblado and within Provenza— neighborhoods packed with expensive restaurants, bars, and a host of nightlife.

The ‘rich man’s cocaine’ is still, well, cocaine

Prices for a single gram of cocaine in El Poblado can reach COP 500.000 COP ($125.00 USD). As is the case with most illicit markets, prices are not transparent across regions, which makes generalizations and academic study difficult. Nonetheless, Pirate Wire Services contacted multiple people involved in the trade within the city, both as customers and suppliers, and was able to obtain a rough survey of price ceilings.

A local source explained to PWS that it’s relatively simple to sell drugs in tourist hotspots such as El Poblado. The supplier described two methods suppliers use to grab tourists’ attention while keeping a low profile.

The first consists of having young female associates club-goers acting as “middlemen” , searching for potential clients, particularly foreigners, inside clubs and bars. These associates are responsible for the bargaining and the exchange process while the actual suppliers stay in movement around the zone— keeping in touch via a burner phone.

Some dealers take a more obvious approach, especially late at night once clubs are full and many patrons become visibly more intoxicated. Using a cover as local hawkers selling beer, cigarettes, or bubblegum in front of crowded venues, they whisper to tourists walking in and out if they’d like some “white powder”, and then selling cocaine under a beer or inside a cigarette carton (though each dealer carries has their own method of performing the handoff).

For foreigners, propositions to buy cocaine happen so often that it can become annoying— as dealers offering the drug grow increasingly bold.

Comparatively, Bogotá’s drug market is more underground, relying on local markets and features less of the wild price spectrum found in Medellin.

According to one drug dealer in Bogotá, who asked to remain anonymous, "purchases are usually made over the phone, with phone numbers provided by known and trusted clients”, with some services even offering home delivery or setting up an appointment in parks or main streets through Chapinero, a popular locality within Bogotá. Our source suggested that a gram of cocaine can cost an average of COP 20,000 ($5.00) depending on the neighborhood, while in exclusive places like Zona T or Parque de la 93, areas popular among foreigners and those seeking upscale nightlife, the same gram can cost up to COP 60,000 ($15.00) or upwards, depending on the hour of the day.

Rising consumption also means rising violence in Colombia

The large difference in prices for cocaine between the two cities also reflect a large difference in consumption.

According to a recent study by Universitat Jaume I, through testing of urban wastewater (think of it as a giant municipal pee-test), the highest average weekly cocaine consumption in Medellín was 3,022 mg/day/1000 inhabitants—while in Bogotá it was 742 mg/day/1000 inhabitants.

The study suggests that domestic cocaine consumption is more than 4 times higher in Medellín than in Bogotá. And domestic consumption across the country is on rise dramatically compared to a decade ago (though that isn’t completely the fault of visitors, Colombians are more likely to use cocaine than a decade ago as well).

Coca cultivation, the raw ingredient in cocaine, has skyrocketed in Colombia in recent years. According to the UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime), coca cultivation increased by 43% in 2022 compared to the previous year, and the country is producing so much of it that farmers who grow coca are experiencing a humanitarian crisis due to a massive drop in prices.

But despite differences in consumption between Medellin and Bogotá, the real danger of this trend is the empowerment of regional cartels and criminal armed groups in Colombia— which as PWS has reported extensively— cause violence, destabilization and human rights violations in the regions they control.

Medellin is located directly on Colombia’s largest drug corridor, a route that hasn’t changed since Pablo Escobar built an empire that exported cocaine through Central America and the Caribbean Sea to reach the North American market.

In Medellin, Mexico-based Sinaloa Cartel, has already established a significant presence in the region, as confirmed by recent Colombian intelligence. Narco-paramilitary groups, such as the Gaitainista Self-Defense Forces (AGC), who the government often refers to as Clan del Golfo, were created in Antioquia in the 90’s and continue to maintain a firm grip on the area.

AGC, direct descendants of infamous right-wing death squads during the civil war, the AUC, are now the largest criminal group in the country and control significant parts of Antioquia, the department where Medellin is located.

Medellin’s tumultuous history of drug-related violence left scars once earned it notoriety as one of the most violent cities in the world. Although it may seem like those dark days have passed, the truth is that most of that violence simply now takes place in more rural regions of the country where armed groups hold control rather than in the urban centers where they profit.

Medellin's newfound international appeal, fueled by its vibrant culture and burgeoning tourism, also has a darker side as a myriad of criminal organizations vie to dominate lucrative cocaine markets while keeping a low profile within the city itself.

All of that is to say, there is no way to “ethically source” cocaine. And while those who buy cocaine in Med may not have bad intentions, that’s irrelevant to the fact that they are fueling violence in the country they’re visiting.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Ex-President of Guatemala, Otto Pérez Molina, who was forced from office in 2015 by anti-corruption protests, pleaded guilty this week to money laundering, fraud and corruption— and will face eight years in jail.

Prosecutors say he received millions of dollars in bribes in exchange for awarding state contracts to various companies. The 72-year-old has been in jail since his arrest the day after he resigned.

He and his vice-president, Roxana Baldetti, had already been found guilty last year of running a bribery scheme at the Guatemalan customs authorities.

Both corruption cases were uncovered with the help of the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), a body created by the United Nations in agreement with Guatemala to stamp out corruption in the Central American nation.

Mexico decriminalized abortion nationally on Thursday. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of a challenge to the existing law in the northern state of Coahuila, stating that criminal penalties for terminating pregnancies are unconstitutional.

Though already decriminalized in some Mexican States, the ruling now protects the procedure nationally, making the country the latest to join the “green wave” regionally in Latin America.

What we’re reading

Our colleagues at the Border Chronicle wrote an excellent piece on how the U.S. has outsourced its border enforcement to Central and South America. As author Todd Miller described it:

“In other words, like Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and southern Mexico, Panama’s Darién Gap has become a part of the U.S. border. Entire countries have become the U.S. Border Patrol’s newest hires, and the Biden administration seems to be banking on this investment.”

You can find the full piece, “A Return on Our Investment: Border Externalization in “America’s Backyard” under the Biden Administration” here.

Spanish word of the week

Tirar la casa por la ventana - Taken literally, this phrase would mean “Throw the house out the window” but the expression is used to describe when a lot of money is spent to throw a celebration.

The expression dates back to 1763 when the King of Spain, Carlos III, organized a lottery to raise money for the state. If someone was lucky enough to win the grand prize, they’d have enough money that they could (if they so desired) throw all their old furniture out of the window and buy totally new replacements! In other words, they had the money to make an unrestrained expense.

One day at PWS, we hope to earn enough to tirar la casa por la ventana

Speaking of which, if you haven’t taken out a paid subscription, please consider doing so. It’s just $5/month! It might not seem like much, but it allows us to keep bringing you the indie journalism and the stories the big guys miss!

And if you have, thank you.

Hasta pronto, piratas!

The violence is the fault of prohibition itself. We went through this with alcohol, a much worse drug by many metrics to cocaine free of cuts with all sorts of profit-boosting adulterants. Global cocaine legalization would have no worse effects on society than the legalization of alcohol. But don't take my word for it; just ask the Colombian president himself:

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/cocaine-is-no-worse-than-whisky-colombian-president-says/ar-AA1yzxxq.

And "90's" should be "'90s".

Otherwise, an elucidating and useful article!

This was a very interesting read. I’m planning to live in Medellin for a few months. I didn’t realize more expats meant increasing coco prices. Thanks for sharing.