ICE is a Terror organization

Formed based on counter-insurgency theory developed by paramilitaries during the Cold War, the organization's actions fit even the FBI's definition of "state sponsored terror"

Men in military-style uniforms and assault rifles deployed from unmarked civilian vehicles — their faces covered by black baklava-style masks — and rushed towards a community center in the middle of the working class neighborhood as shocked residents watched in terror from the windows of their homes, or fled public space in the vicinity.

They were backed up by national military units and anyone who resisted, or tried to aid those who resisted, was arrested. Agents required no proof: none was necessary. Even long-term residents of the community were detained, as was anyone who resisted, or aided those resisting.

For people in the United States, images such as the ones above have become commonplace as agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) terrorize communities and detain thousands, most of whom have no criminal record.

But for people in Latin America, especially in Colombia, where I have lived and worked for over a decade, the operations ICE is currently conducting in urban centers around the country, such as Los Angeles and Chicago, conjure up a familiar and terrifying image of other paramilitary forces: the right-wing death squads that fought on the side of the Colombian government during the country’s 53-year civil war.

For decades, the “United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia” (AUC) committed grave human rights abuses, including kidnappings, forced disappearances, and assassinations as part of a terror campaign meant to intimidate the civilian population and defeat an armed leftist insurgency by any means necessary.

Originally supported by the U.S, the AUC worked regularly with official Colombian military forces, and was originally green-lighted (and partially funded) by the Colombian government.

The AUC quickly developed a horrific record of human rights abuses which included kidnapping, forced disappearances, and assassinations, which was strongly criticized by the international community.

They were eventually declared a “terrorist organization” by the U.S. State Department in 2001, though financial and material support for a “Dirty War” carried out by the Colombian government continued through Plan Colombia, in which the U.S. funded counter-insurgency operations in the country for almost a decade.

The similarities, however. between paramilitary groups here in Colombia and the state-sponsored terrorism of ICE operations are obvious: heavily armed anonymous masked men imposing control and imposing terror and control on a perceived “internal enemy” within the country.

Viewed in the context of U.S. actions in Latin America, the reasons for the similarities make sense. ICE was originally developed as part of the same counter-insurgency tactics that the U.S had learned in Latin America, and granted broad legal powers to “combat terrorism” in response to 9/11.

Lessons learned by U.S. security forces in Latin America (not just in Colombia but across LATAM in places like Nicaragua, Chile, Argentina and El Salvador), were incorporated into the creation of ICE by U.S. President George W. Bush.

And support for ICE has been bipartisan. Shortly after President Obama took office in 2009 he massively expanded the organization in terms of logistical capabilities, funding and personnel. He was the first president to use the newly minted security force to carry out mass deportations.

At the time, despite human rights organizations calling attention to ICE’s deplorable abuses, and an active if small “Abolish ICE” protest movement, criticisms of ICE did not resonate broadly in the public imagination.

But current U.S. President Donald Trump has made ICE abuses impossible to ignore. Instead of trying to sweep them under the rug as previous Presidents have done, he and his subordinates parade them publicly, including via social media accounts that often attempt to mix humor with dehumanizing statements or threats.

“If you’re a criminal alien, we’re coming for you,” ICE regularly says in public statements, a broad category considering that more than 70% of migrants detained by ICE have been convicted of no crime at all.

But the parallels between ICE and paramilitary groups in Latin America throughout history go beyond mere aesthetics. They get at the very root of what the word “terrorism” means in contemporary society.

The definition of the term “terrorism” is often debated even among the academics who study it. But it came into usage originally to describe actions by states who used violence as a tool to instill fear or intimidate their opponents.

It was regularly used by U.S. officials at the time to describe actions by Nazi Germany in regards to Jewish and gypsy populations, as well as Russian actions under Stalin, including “the Great Terror.”

But during the Cold War, the United States, as well as many U.S. and European Scholars, began to claim that “terrorism” as a legal term could only apply to non-state actors. By the 1970s, in part due to U.S. actions in Vietnam, the U.S. had changed their domestic legal definition to exclude nations.

It was a convenient distinction. Legally, the U.S. de facto could no longer commit “terrorism,” despite directly supporting a number of groups actively engaged in it, and despite ongoing actions that would have been considered “state terrorism” under the previous definition.

By the 1980s, at the height of the Cold War, the U.S. was directly supporting groups that the country would previously have considered “terrorist groups,” such as the Contras in Nicaragua, and Pinochet in Chile.

The FBI and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which has operational control over ICE, define terrorism as violent actions which “intimidate civilian populations”, “influence the conduct of a government by assassination. kidnappings,” or “ethnically motivated violent extremism (REMVE).”

ICE has regularly carried out operations which have no practical purpose other than to sow terror in Latino communities, such as a massive deployment at a park in a migrant community in Los Angeles, which included armored personnel carriers and mounted, heavily armed officials.

Agents threatened medical staff who happened to be in the park as well as local residents, but made no arrests.

ICE has been widely accused of using racial profiling in its detentions of Latino populations, and the vast majority of ICE operations occur in Latino communities.

Officials from the organization deny the accusations, saying that a few extreme cases of “over zealousness” on the part of individual officers does not constitute a pattern, and that the agency engages in “meticulous planning” over its operations, saying that race is not a factor in operations.

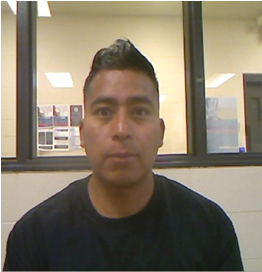

A PWS survey of ICE public statements, however, paints a very different picture. ICE posted the names of “illegal migrants” it detained 82 times on its X social media account between July 10 and July 20.

Seventy-one of those detained, representing 86% of detainees, were from Latin American countries. Ten others were from Asian or African-Middle Eastern countries. Two were from Romania. Of the 82 photos and names posted, only one could be considered “white” or Caucasian, a man from South Africa that ICE said was detained on July 14.

ICE actions fulfill the FBI’s definition of “state-sponsored terrorism”, (a term the U.S. invented after 9/11 to describe “state terrorism”, which according to their most recent definition of the term is a legal paradox).

Trump has repeatedly threatened migrant communities, as does ICE daily in public statements. The Trump administration, much like paramilitary organizations in Latin America throughout history, has also gone after civilians it views as aiding the “internal enemy.”

The administration has repeatedly threatened sanctions, and even legal actions against migration attorneys who speak out against ICE actions.

Even the legal justification by which ICE has been deporting migrants on U.S. soil conjures up memories of bloody counter-insurgency operations in Latin America: the Insurrection Act, by which the administration argues the U.S. is being “invaded” by foreign nationals.

So is ICE engaging in “terrorism?” Conveniently, U.S. law excludes any action undertaken by the U.S. from that definition. In most Latin American countries, however, including those that have suffered under State Terrorism for decades, the answer is an unequivocal “yes.”

You can also donate a one-time gift via “Buy Me a Coffee”. It only takes a few moments, and you can do so here.

And if you can’t do any of that, please do help us by sharing the piece! We don’t have billionaire PR teams either.

Hasta pronto, piratas!

Great piece!

safedc.info