'I'd be dead without Punk Rock'

How a global cultural revolution found an unlikely permanent home in the working class barrios of Medellin

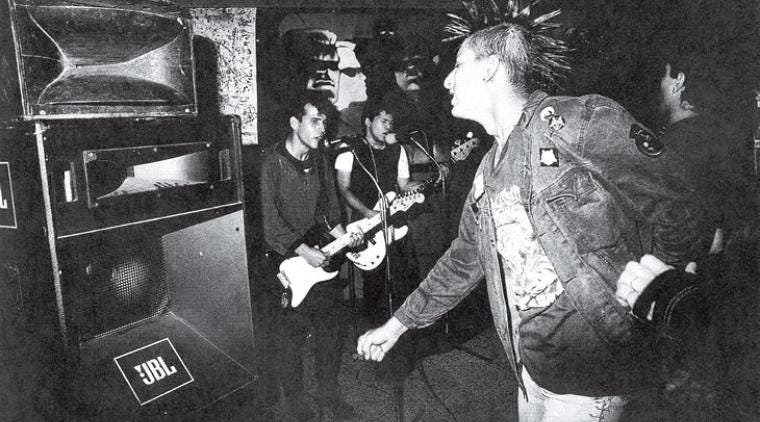

A singer with a silver jacket covered in spikes screams into a microphone hooked up to an oversized stereo speaker. The guitarist behind him, his instrument slung so low it rests near his knees, writhes to the hardcore rhythm he beats out with a furious intensity.

The crowd is made up of young people, clad to the attendee in black. But what they lack in diversity of wardrobe color palettes they make up for in hairstyles, which range from neon blue bob cuts to mohawks that reach impressive heights.

A mosh pit rages in the center of the concrete football court where the outdoor concert is being held in this working-class barrio called Santa Domingo, in Medellin, Colombia. While young punk-rockers shrouded in black cover most of the surface of the football court, curious neighbors, dressed in a typical tropical rainbow of colors look on with curiosity and bemusement — many drinking beer and shouting their approval between the songs

The vecinos have come out to see what the party is all about, and based on their enthusiasm it seems they approve.

I’m at a D.I.Y punk show in Medellin late in the year of our lord 2024, and based on the number of attendees, I’d venture that rumors of the genre’s demise have been greatly exaggerated.

As I’m thinking those very words, as if on cue, the singer grabs the microphone and screams “Punk is dead! Long live Punk, you sons of bitches!”, which elicits wild screams from the crowd.

I am enchanted. I am also perplexed. How is this scene so vibrant, so viable, so clearly durable, and so, f… well, we try not to veer into vulgarity in our journalistic style here at PWS. After all, curse words are sometimes the refuge of those who lack better methods to communicate their ideas and emotions.

But since this is a punk show we’re attending perhaps I can throw caution to the wind and simply ask, how is the scene here so fucking cool? What is this?

The answer to that question, dear reader, led me down a months-long rabbit hole of rebellion, magical realism, civil war, and social uprising that at every turn only fascinated me more.

“Do-It-Yourself” in an Age of War

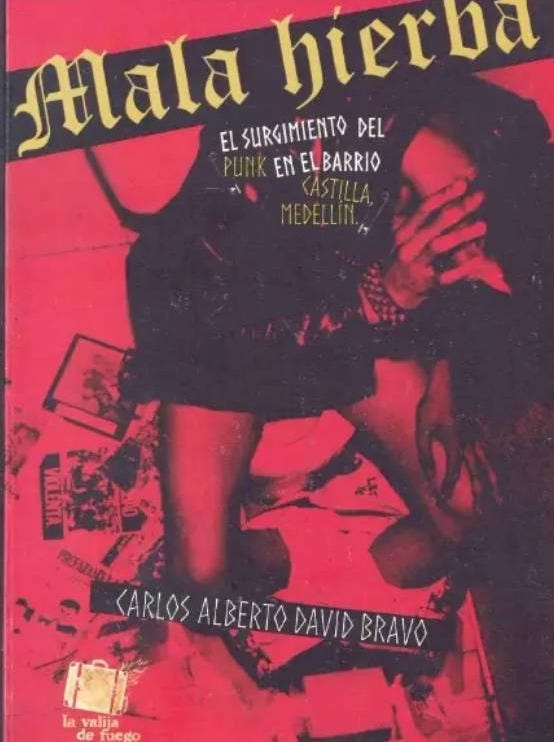

People I talked with about the history of punk rock in Medellin pointed me to a book called “Mala Hierba” by Carlos Alberto David Bravo, a drummer in a punk band called “Desadaptadoz” (Misfit loosely translated), founded in 1987.

Of course, I immediately stole it. Well, from a website that hosts it in PDF form for free. But even better, I learned that he still gives monthly talks on the scene in Castilla, one of the neighborhoods that formed the backbone of the emerging Med punk rock scene in the 1980s.

In the 1980s, the social situation in Medellin was decaying rapidly, even as the city was growing at incredible speeds. The Colombian civil war was starting to pick up steam in the countryside, and many victims of that conflict, as well as those displaced by it—which would enter its most violent period in the 1990s and early 2000s—were fleeing to cities.

Medellin, however, was also plagued by other conflicts. It was the age of the Medellin Cartel, which was growing even faster than the city. Under the leadership of Pablo Escobar, the cartel had grown to dominate narco-trafficking not just in Medellin, but in all of Latin America.

And in the 80s the cartel, alongside the Colombian government, went to war with leftists in all of Colombia— a bloody and ruthless campaign that had an outsized impact on Antioquia, the region where Medellin is located.

By the mid-80s, however, the Cartel was also at war with the Colombian state.

“You have to understand the context that we grew up in,” said Bravo at his talk in La Castilla. “We were at war in every sense — literally yes, but also socially, politically, criminally, and mentally.”

Punk rock as a genre emerged in the late 70s in London and New York and exploded into the mainstream worldwide in the early 80s. It didn’t take long for the counterculture to reach Colombia as well.

“For the rich kids, maybe their friend who was sent for a semester to a University in the U.S. or the U.K. brought back albums that fired up their imaginations,” said Bravo. “For us, in the barrios, maybe one of us got ahold of an old mix tape, or maybe a relative who had migrated to the U.S. for work sent us a cassette in the mail.”

These were pre-internet times. But how the youth of the day got their hands, and their ears, on the music didn’t matter — a cultural explosion had begun.

The punk scene within Colombia is more well-known in Bogotá, the capital and a larger city by an order of magnitude. But Bogotá, though it was also touched by conflict, was in comparison isolated from the war raging in the country’s rural areas.

Medellin, on the other hand, was right in the midst of the chaos. Between 1989-91 it had the highest murder rate on earth. The “most dangerous city in the world” was reeling from a series of different complex conflicts between multiple actors — not least of which was the birth of “paracos”, the right-wing paramilitary ‘defense forces’ that would later become world renown for their brutality, human rights violations, and wanton murders.

“So when I say I grew up in war,” said Bravo, “this is not a euphemism.” For Bravo, punk rock wasn’t just a musical genre, it was a philosophy. “It was a rejection of everything I hated or feared,” he said. “It was about creating a new culture that rejected the State. rejected the violence of paramilitaries, the obsession with money and consumerism of the narcos, and the ignorance and brutality of the fascists,” he said.

“It embraced freedom and the idea of building something more, something better.”

An Ethos of Constructive Chaos

And it was a philosophy that exploded especially among the youth in the working class barrios of Medellin— a population much more likely to be overlooked than college students in the capital. And perhaps because of their unique circumstances, punk culture found a soil more fertile and lasting than anyone could have possibly expected.

“We were the weeds (hierbas malas) in the ‘City of Flowers’”, said Bravo, citing one of the nicknames given to Medellin by its residents, and also explaining the title of his book. And grow like weeds they did.

The D.I.Y ethos of punk took root especially among the kids from the barrios, who commandeered gymnasiums, schools, football courts, abandoned properties, houses, and any other site they could to organize shows for the burgeoning scene.

“It was an opportunity to criticize our society, the violence, in a place where death could be waiting for us on any corner at any moment,” said Vicky Castro, singer for the feminist band “Fertile Misery”.

In “Medallo Punkero” an audio piece produced in 2011 that consists of hundreds of interviews with people who participated in the cultural movement, one unnamed man said “For me, punk was the opening of a door. Punk led me to Anarchism, and that led to the idea of feminism, which to me at that age, was a completely unknown term.”

“It’s the first time I realized how misogynist the society I grew up in really was. I knew I had to help the camaradas (Spanish female plural form of the noun “comrade”) wreck all this shit. We needed something better, something fairer, something where we are all one,” he continued.

“I have no idea where I would point a gun,” said Bravo, “but I know exactly where to point a guitar: at power. Punk rock saved me from joining that fruitless war. I’d be dead without punk.”

But the growing scene also drew the ire of both state and non-state forces. Colombia’s Truth Commission, which is in the process of investigating the atrocities that occurred during this period in Colombia, wrote this year that “Paramilitary structures and state forces viewed the emergence of some of these new cultural niches with suspicion. Many of these expressions were singled out and persecuted, and artistic groups were accused of propagandizing for subversive groups.”

In the 90s, Paramilitary forces carried out a series of “social cleansings” in Medellin. Thousands of youths were disappeared or murdered in the city as part of those operations.

“A lot of those were punks,” said Bravo. “A lot of them were my friends.”

But the violence, the suspicion, and the persecution from authorities didn’t stop the punk scene. It fortified it in the culture instead. “We were ‘resistance’ in a pure form,” said Vicky Castro, the singer from Fertile Misery. “And it didn’t hurt that we threw a hell of a party.”

Punk rock, of course, still exists in Bogotá. But Bravo believes that it took root more profoundly in Medellin than in most of the other cultures it spread to. “We were punk rock,” he said. “It was the life we lived.”

When I asked Valery, a young Colombian at the concert I attended in Santa Domingo, what she thought of punk, her initial answer had so many curse words I’m honestly not even sure if an English translation could possibly do it justice (it was positive though, dear reader. Suffice to say she is a fan).

But when pressed for specifics, she spoke of Colombia’s deadly 2021 protests, which included a national strike and the deaths of at least 60 protesters. “Punk is resistance,” she said. “Punk is the people. Punk is a struggle against injustice.”

Indeed. And in Medellin at least, it is also a multi-generational cultural phenomenon, a history class, and a lecture on philosophy all rolled into one.

Long live Punk Rock.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Nicolas Maduro will re-assume the presidency of Venezuela on January 10 after a victory in elections that was widely viewed as fraudulent. Edmundo Gonzales, the opposition candidate who is believed to have won the popular vote fled to Spain in September. But he has promised to return in protest of Maduro’s swearing-in.

Opposition leaders have called for mass protests, and Gonzales, after a short tour of Latin American countries, plans to re-enter the country, despite an arrest warrant issued by Maduro.

We’ll be doing live updates on J10 here on the website. Tune-in for that. It will be a dramatic day in Venezuela.

Ecuadorian officials have confirmed that the charred bodies of four boys — aged 11 to 15 — found in the city of Taura, are four boys who went missing on December 8 after being taken into custody by the military.

A judge has ordered the detention of 16 military officials accused of involvement in the murders. The families of the missing boys said they had gone outside in the l city of Guayaquil to play football when they disappeared.

The boys disappearances took place in the midst of police crackdowns as part of a state of emergency that grants broad powers to security forces. Similar measures have long been linked to human rights abuses in Latin America such as forced disappearances, extrajudicial executions, and mass detentions.

Trinidad and Tobago has declared a state of emergency over soaring murder rates that will grant broad powers to police, including warrantless arrests. Authorities blame organized crime for the rise in violence. The dual island nation’s location, close to Venezuela, makes it an ideal for drug shipments moving north through the Caribbean as well as east to Europe.

President Christine Carla Kangaloo issued the declaration on the advice of Prime Minister Keith Rowley. The two say that the state of emergency — for now — does not include a curfew.

The Ship’s Log

We’re back and headed into the new year! Latin America, and migration, two of our principal beats are going to be more important than ever in 2025. With Trump taking office in the United States and xenophobia on the ascendency globally, we will likely be sailing into rough seas here at the Good Ship Capybara.

But pirates have no fear. We’re already sharpening the sabers and battening down the hatches and are ready to wade into the melee with our usual hard-hitting style. In the meantime, Joshua is still in Medellin, though he has applied for work in the U.S. doing investigative work into migration on the Mexican border.

Daniela is still in Mexico City as part of a scholarship she won for her Spanish-language coverage on feminism in Latin America. She reports that her plans to eat all the street tacos in the city are going well, as are her more journalistic projects. She is in the process of organizing a trip to visit the Zapatistas!

If it works out you can expect front-line coverage here at PWS.

What we’re writing

Joshua and Daniela wrote a piece for World Politics Review about how dependent the United States has become on Mexico to limit migration at the U.S. border. “Mexico Is Doing the United States’ Dirty Work on Migration.” Trump’s pledges to “secure the border,” are dead in the water without Mexican cooperation and the dynamic gives Mexican President Sheinbaum much more leverage than Trump lets on.

In a debut appearance at Mongabay, Joshua wrote ‘An underground gold war in Colombia is ‘a ticking ecológical time bomb’ The Zijjin mine, operated by a Chinese conglomerate in Buriticá, has become a subterranean battlefield, and the environmental results could be devastating.

Spanish word of the week

díscolo (adj) - wayward, fractious, disobedient. As punk rock often is.

A pesar de su comportamiento díscolo, Pepe es muy querido por sus profesores. — Despite his unruly behavior, Pepe is well-liked by his teachers.

Not to be confused with Disco Lo, Joshua’s alter ego who comes out late at night on Fridays

Hasta pronto, piratas!