‘National Armed Strike’ by Colombian rebel group demonstrates their growing power

The action's widespread impact casts serious doubt on the government's claims that they're beating the rebels back

“Cúcuta is paralyzed,” said Ulises Hadar, a journalist from the city on the Venezuelan border. “There are no functional highways leading into the city. It’s like a game. Yesterday the National Liberation Army (ELN) left a few bombs on the roads, today a few more. Who knows what tomorrow will bring?”

The ELN is a leftist revolutionary group which does not recognize Colombia’s 2016 peace deal and has been at war with the Colombian government since the 1960s. Last week, they imposed a 72-hour “National Armed Strike” in the regions of Colombia they control, shutting down critical infrastructure such as the Pan-American Highway.

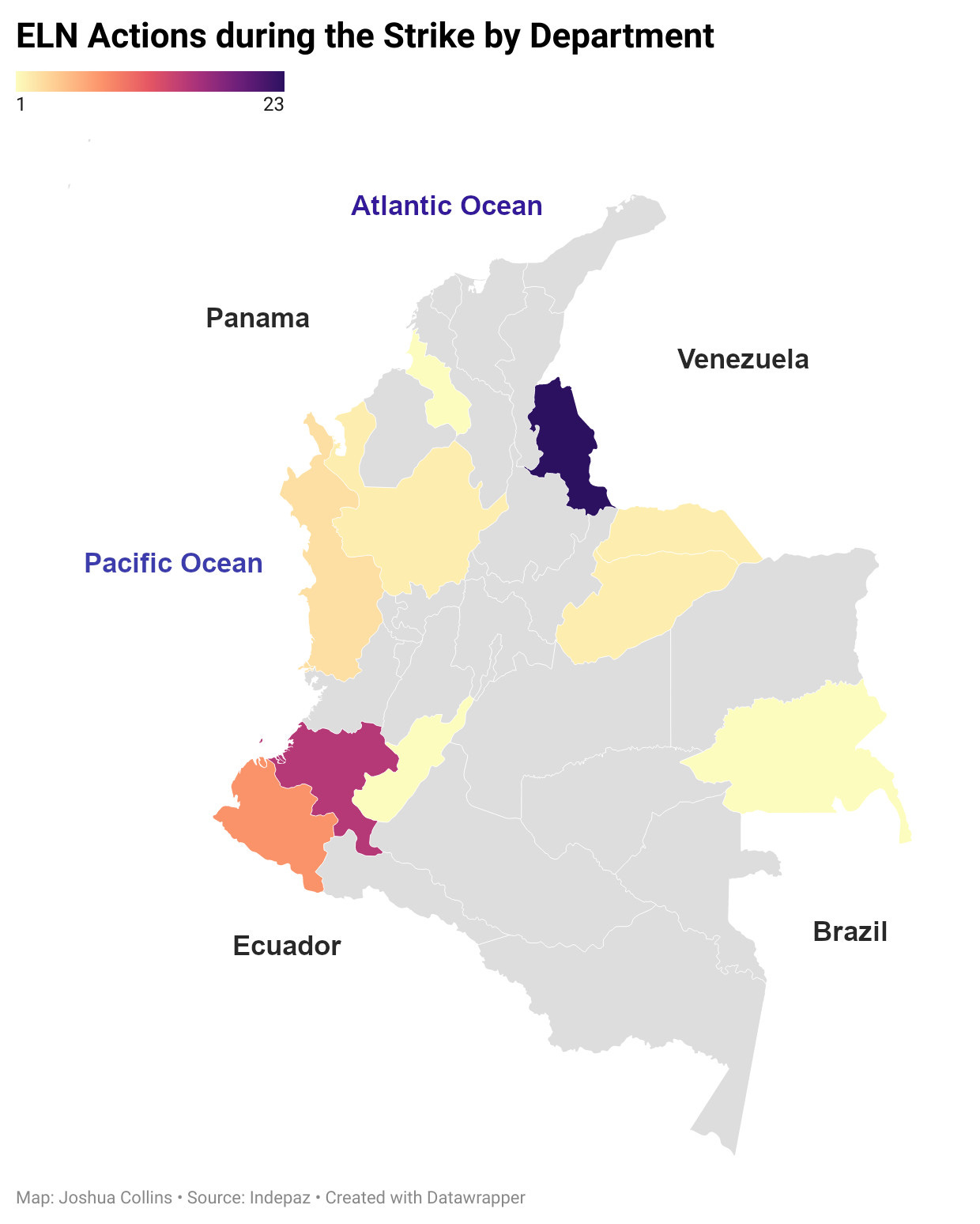

During the strike, peace monitoring nonprofit Indepaz registered 65 incidents in 17 departments including blocked highways, burnt trucks, bombings, and an armed attack on a police station.

The actions clearly show the group’s power is increasing: a similar strike in March 2020 saw just 27 incidents in nine departments, according to figures from Colombia’s peace court. For the government, which claims that its aggressive military action has ELN power on the wane, the images of guerillas in uniform openly patrolling towns under their control were damning.

“They hang up their flags on the highway,” said Hadar, “And everyone is afraid to take them down. Even the army.”

ELN announced the 26-28 February armed strike a week in advance, in a public statement that decried the “narco-terrorist capitalism” of the “evil government”, citing what they claim is government complicity in drug trafficking and rising violence against Colombian activists.

Defense Minister Diego Molano publicly assured Colombians that the state would not permit the ELN strike to disrupt transportation in any part of the country. “Colombia will not be intimidated by a few ELN pamphlets,” he assured. “The country must trust in the abilities of our public forces. ELN are nothing but cowards that hide in Venezuela.”

During the strike, he pointed to the arrests of five ELN members as evidence that the group was losing power. And yet, ELN operations went largely unchallenged by armed forces, who took no major actions to disrupt the strike. Many commentators were quick to compare the non-response to a brutal police crackdown that killed dozens of demonstrators during massive civil protests last year.

After the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) disarmed as part of the 2016 peace accord which ended their 52 year war against the government, the vacuum they left behind was quickly filled by a plethora of armed groups ranging from dissident FARC forces to right wing paramilitary narco groups like the Clan de Golfo. The resultant turf wars have driven a spike in violence: 2021 saw the most massacres since 2014 and the country still has the most murders of activists and social leaders in the world. The ELN has seen the biggest gains in this battle for territory, growing substantially in both numbers and territory.

ELN rejected the 2016 deal, and after the government suspended further talks, bombed a police academy in Bogotá in 2019, killing 21 people. Since then, Duque has ordered security forces to relentlessly target ELN operations and operatives, even using the air force to bomb encampments. Drug seizures and arrests are common, but they have not slowed ELN growth.

Colombians go to legislative elections on March 13, and victims of the civil war are guaranteed a number of seats in Congress for the first time as part of a recent ruling by Colombia’s Peace Court. Current leftist frontrunner for May’s presidential elections, Gustavo Petro, has promised to re-start dialogue with armed groups like ELN as well as re-implementing aspects of the peace accord that the current administration has stonewalled or ignored, such as investment in conflict zones.

“The government claims that they control [these conflict zones],” said Hadar, “and that criminal structures are in decline. But it’s not true.” In Norte Santander department alone, within the past year the government says the ELN has attacked the presidential helicopter with small arms fire, planted two car bombs, one of which exploded outside a military base in Cúcuta, and attacked the airport, all while waging war with half a dozen other armed groups in the region.

“This armed strike just further illustrates what everyone who lives here already knew,” Hadar continued. “These regions have been all but abandoned by the state, and armed groups have moved in.”

“Like always in war,” he lamented, “it is the civilians who suffer.”

What we’re watching: the bad…

Argentine society has reacted with horror after six young men were caught raping a woman in a car in the upscale Buenos Aires district of Palermo on Monday afternoon. The car was parked outside a bakery, whose owners called the police and confronted the rapists with broomsticks. The attackers included middle-class students and a political activist. The case has prompted soul-searching questions about toxic masculinity and how boys and men are socialized in Argentine society.

There are nearly 100,000 disappeared people in Mexico. Understaffed forensic teams and families are on a mission to find out what happened to them. Be warned: right from the start, this is more graphic than any reporting we have yet to see from Ukraine…

…and the good:

This week Costa Rica became the 11th Latin American nation to legalize medical marijuana. So far Uruguay is the only nation in the region to legalize the drug for recreational activity, but both candidates in the April 3rd presidential run-off in Costa Rica support full legalization.

An epic rap battle between Colombia’s son, J Balvin, and Residente, the singer of Calle 13 took an epic new turn this week. Residente dropped an absolutely blistering diss track on poor J Balvin, who has not been heard from since, and is rumored to have died after listening to it. The two began feuding during Columbian protests last year after Balvin refused to support protesters, despite nearly every artist in Colombia publicly calling for police to stop killing people. The feud escalated when Balvin cried publicly about not winning a grammy for a song he didn’t write. But the new track seemingly puts an end -if not to which of the two is correct- then certainly to who is the more talented rapper.

Spanish words of the week:

resquemor (m) - fear, resentment or disappointment. Yup.

Cachaco (m) - Cachaco is what Colombian people who live on the coast call all the sad, jealous, miserable, pale people who live in the interior of the country and are not able to wake up looking at the sea.