New data on conflict in Colombia paints an uncertain picture

How has Petro fared on security, "Total Peace" and inequality? We explain it all with 5 numbers (and some charts)

President Petro will soon be nearing the halfway point of his administration in Colombia, and despite grand ambitions, he has few concrete political victories to point to.

His vision of “Total Peace” for the country, which includes direct negotiations with criminal and rebel armed groups in return for their disarmament, has yielded mixed results— and newly released data on conflict, violence, economic activity, and crime from 2023 paints an unclear picture of where the country is headed.

This week we’re trying something a bit different. We want to take a look at where Colombia stands on all of these issues with a focus on the data. With that in mind, we’ve created some interactive graphics (assuming you’re reading this on the website and not via email) to examine some crucial questions.

How are the government, and the country, doing? We’re so glad you asked. Read on!

Is the security situation getting better or worse?

There isn’t a simple answer to this question. Violence stemming from Colombia’s ongoing conflict has slightly improved by some metrics, worsened by others.

Immediately after Colombia’s 2017 peace deal with the rebel group FARC, homicides dropped greatly (continuing a long-term trend since the early 2000s, when Colombia was one of the most dangerous countries in the world).

But they began to increase again soon after (under the previous administration of Iván Duque), as other armed groups moved into the power vacuum left behind when the FARC disarmed— and began fighting over their former territories.

Annual murders sky-rocketed immediately after the COVID pandemic, reaching levels not seen since the civil war. After Petro took office in 2022 they began to drop off slightly, but numbers were on a slow rebound again in 2023.

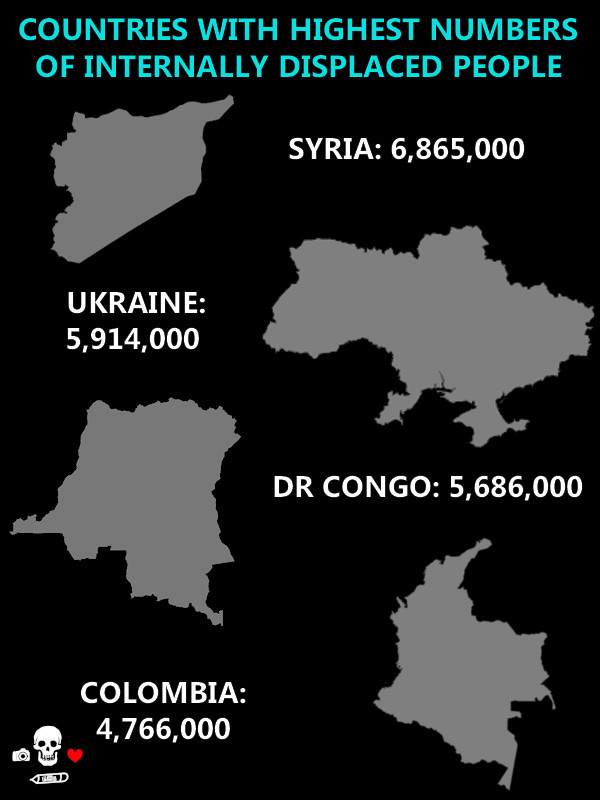

Colombia has long struggled with people internally displaced by armed conflict (IDPs). For decades Colombia had the highest amount of IDPs in the world. Syria, Ukraine, and DC Congo have since surpassed Colombia, but the Andean country remains in 4th place for Internally displaced people globally.

During Petro’s first year in office, the number of those displaced by conflict reached an astonishing 339,000— a number not seen since the height of the country’s civil war in the 90’s.

The spike of displacements was due to two factors: a series of “armed strikes” by the two largest criminal organizations in the country, the National Liberation Army (ELN), and narco group the Gaitanistas (AGC by their Spanish initials), as well as new fighting between groups jockeying for power and territory ramping up to negotiations with the government.

In 2023, however, that number dropped to 166,555 people— a shocking number for those unfamiliar with the Colombian conflict, but largely on par with the previous two decades.

What is the situation with Armed Groups?

The two largest remaining armed groups in the country have both expanded in territory and power since Colombia’s 2017 peace deal with the FARC. Marxist rebel group the ELN has particularly benefitted from expansion into territories formerly controlled by the group.

ELN is about to enter a third round of formal talks with the government and currently has a ceasefire with security forces. In areas where ELN has uncontested control, violence has dropped as a result.

Though some “fronts” of the rebel group have continued kidnappings as part of extorsion attempts, and at least one faction has conducted an “armed strike”, shutting down highways and prohibiting residents from working— both technical violations of the deal.

AGC, a narco-paramilitary organization, and ideologically descended from the right-wing forces that fought on the side of the government during the civil war, entered into formal talks with the government last year, but the efforts quickly collapsed.

They have consolidated their control on the Northern Coast, where they were originally founded. Currently the largest criminal group in Colombia, they also benefit from deep infiltration within security forces and contacts within the legitimate business community.

Massacres, which Colombia defines as single-event killings in which 3 or more homicides occur, have not abated, with over 300 victims of such incidents in 2023. They are most common in regions that are contested by armed groups rather than the regions firmly controlled by criminal elements.

Contested regions are most common near borders and along major cocaine smuggling routes, and that violence often spirals into aggression against residents: as shows of power, intimidation efforts, or retaliation against those armed groups consider to be sympathizers of rival groups.

“Total Peace” has so far been unable to stem intra-armed group violence in any meaningful way.

What about Economic Reforms?

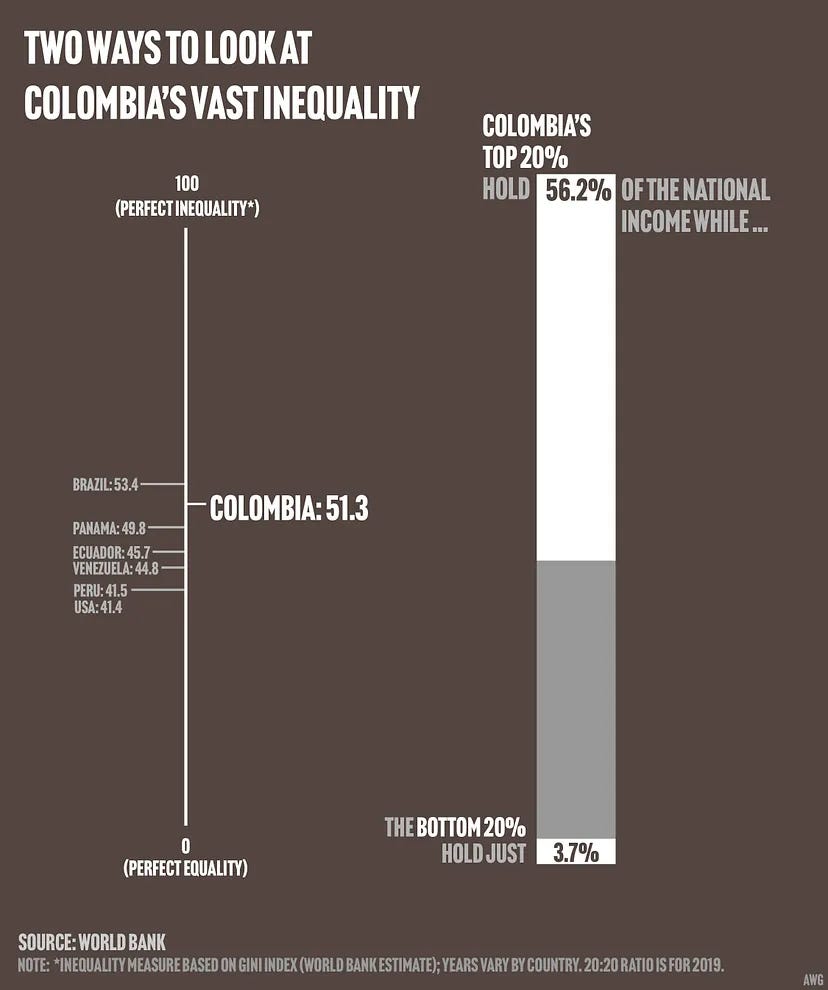

Petro promised to bring sweeping economic reform to Colombia and address its longstanding inequality, which, depending on how it is measured, is one of the highest in the Americas. But aside from a few early victories, his economic agenda has been largely stymied by Congress.

The political coalition he built after assuming the presidency collapsed last year, with former allies now acting as “Independents” who have at times joined the opposition in blocking economic reforms.

Though the administration has made some small steps towards giving land to rural poor families that have been displaced by violence, promised systemic changes have eluded Petro, and Colombia continues to be one of the most unequal countries on the continent.

Economic disparity and internal colonialism are the principal drivers of Colombia’s ongoing conflict. Petro is finding out the hard way that it is much easier to talk about ending war on the campaign trail than putting that rhetoric into practice.

“Without peace, there can be no justice,” was one of his favorite phrases as a candidate. For the rural poor in conflict areas, both of those commodities are increasingly scarce.

Some have begun to lose faith that Petro can fulfill his promises. If the trends in Bogota don’t change radically, they may be right.

The Big Stories in Latam

We’ve written a lot about Ecuador this week, and rightfully so. But, sadly, things continue to escalate there. Despite a nation-wide crackdown by security forces (or perhaps at least in part, because of it), the prosecutor in charge of the high-profile case of the live-hijacking of a television station was murdered en route to a hearing on the case on Thursday.

César Suárez was shot dead in the port city of Guayaquil. If you happened to miss it, we covered the explosion of gang violence in Ecuador last week, and the response by security forces as part of our “Ship’s Log” series on Wednesday.

In a speech to the planet’s wealthiest people, Argentinian President Javier Milei gave a controversial inaugural speech at the World Economic Forum at Davos. The West is “in danger” due to creeping “socialism,” he said. He also accused feminism of hindering economic progress and called the billionaires listening to his speech “heroes.”

“Don’t let anyone tell you that your ambition is immoral,” he stated in closing remarks. “You are the true protagonists of this story, and know that from this day forward, you have an unwavering ally in Argentina.”

Unsurprisingly, many of the billionaires in attendance thought it was a great speech. In other news, water is wet.

Ship’s Business

After a sporadic break through the holidays (which included a special report on our trip to the Darien Gap to speak with migrants on Christmas) we’re back to our normal schedule for 2024!

As part of our piratical resolutions for this year we’re planning on launching another podcast season, posting “flash updates” on breaking stories in LATAM (which will probably be published on the website only rather than flooding your inboxes), and officially launching a Quartermasters Merch store.

Since we’re talking about graphics this week, have we mentioned “El Capytán”? We’re trying to get him on T-shirts. He deserves it.

Thanks for being part of our journey as the Good Ship Capybara sails into its third year on the turbulent seas of independent journalism. We’re at nearly 2000 free subscribers!

Your support means the world to us.

Spanish Word of the Week

chino/china (amigo, amiga, niño, maybe sometimes lover?)

The way Bogotanos use this word has always puzzled me, as has the origin of the slang term. Chino literally means, a person from China, but it is often used to refer to children as well: “El parque estaba lleno de chinos,” is referring not to persons of Chinese descendence, but rather a group of kids.

It can also be term of endearment, usually used towards friends: “Oiga chino, ¿quieres ir a la fiesta?” —Hey, bro, Do you want to go to the party?

Even more confusing, I have heard male friends refer to people they are dating as their “chinas”. This has resulted in some problematic translations on my part.

“Wait, you’re dating a child?”

They weren’t, thank God, but even after 8 years I still find the term confusing. I asked a friend of mine what the origin of the phrase is. He replied “Well, Chinese people really like to have babies. There’s a lot of them. I think it comes from that.”

I’m not sure he is 100% right about the etymology, but it was a colorful response. We need to consult a linguist about this I think. Or maybe a historian. Or maybe both.

I don’t know. My head hurts.

Hasta pronto, mis chinos!

I watched Milei's speech. Certainly a sin for the history books. Dig the t-shirt design - exceptional. And I may go on a date with the woman in the header image.