Soup kitchens are Argentina's last bastion against chaos. Can they survive an IMF deal?

If austerity cuts support to the poorest, the consequences will be disastrous

“Ma! You got any hot water?”

The man was peering round the soup kitchen’s door, his avid blue eyes staring out from between a facemask and a grubby woollen cap. I’m not his ma, but all women are “ma” to Buenos Aires’ poorest. I put the kettle on, passing him some sugar and yerba maté in little glass jars.

Across the street, his girlfriend sat heavily on a window ledge, cradling her pregnant belly. It was the depths of winter and Buenos Aires was under COVID-19 lockdown. But you can only stay home if you have a home to go to, and this pair didn’t. As the sallow sun warmed the air until we could no longer see our breath, they brewed their morning mate on the kerbside, coaxing life back into fingers stiff with cold.

As Argentina’s healthcare workers fought to save the sick, community soup kitchens like this were on the front lines of another war: the war against hunger. Inexpert and frantic, we would peel sackfuls of squash, squabble about recipes, and sort through onions that at times were so putrid, they made our noses run into our hastily stitched facemasks.

Outside, an unruly line of the hungry snaked round the corner and down the block, the emptiness in the pits of their stomachs winning over our feeble entreaties that they keep two metres apart. It was a scene that repeated itself inside activist spaces, community centres and churches all over the country. Though they’re generally known in Spanish as comedores, many prefer to give them the more militant name of ollas populares (“people’s pots”): after all, hunger is political.

Although fewer people are turning to these common pots now than during the depths of the pandemic, demand remains higher than in the Before Times, supplies are running out, and the government is facing tough decisions over a beleaguered economy. It’s leaving many wondering how much longer these support networks can hold out.

Statistically speaking, at least, Argentina’s economy is recovering from COVID-19. Industrial production for the January-September period rose by 18.7% compared with 2020. Unemployment has fallen from 13.1% in the second quarter of 2020 to 9.6% in the same period of 2021.

But the economy had been in recession for years before the pandemic. Inflation, a perennial problem in Argentina, is running well above 50% and salaries are falling far behind, pushing the middle classes into poverty and the poor into destitution. Argentines fear that any of the fixes on the table will take a brutal toll on the poor.

The most immediate problem is renegotiating the payment of a massive International Monetary Fund loan, arranged by former pro-market president Macri in 2018. At US$57 billion, it was the largest deal ever agreed by the Fund, although he only drew $44 billion before being voted out in November 2019.

Argentina’s government has promised to make a USD1.8 billion payment due in December. But cash for mounting payment deadlines starting in March 2022 just isn’t there, analysts say. Officials are in a protracted series of negotiations aimed at pushing back the due dates so as to generate the funds without resorting to devastating austerity.

The IMF is notorious for structural adjustment programmes that demand harsh cuts in exchange for financial assistance. It was one of these programmes that worsened a cataclysmic financial crisis in Argentina in 2001, when the country saw five presidents in two weeks as riots took over the streets. Argentina’s dictatorships also took on debts with the fund, a nod to their neoliberal ideology.

Once abundant, the bags of pasta, lentils and tomato sauce that the government used to provide seemed to trickle to a halt. In my comedor, we still got donations from other organizations, but it meant the modest food packages for volunteers - some recently homeless themselves - were curtailed, then virtually eliminated. Throughout 2021, social movements have been marching to the Ministry of Social Development, demanding food for comedores and jobs for the unemployed. In the poor barrios on the outskirts of town, they say, soup kitchens are running out of food.

“It’s like something natural nowadays, that there’s a community soup kitchen [wherever you go in Argentina], and the neighbours, the guys who recycle cardboard in the streets, the people who live in the slums, they form cooperatives and comedores, to supply [...] food,” said Eder Paniagua, who manages supplies at a vast soup kitchen in the headquarters of the UTEP social movement. “They’re key so that there isn’t a social uprising.”

I first met Eder in late 2019, reporting a story about how the falling peso and dollarized commodity prices were sending Argentina’s food prices soaring. Then, his comedor was serving around 1,000 portions of food a day, and it seemed the hunger couldn’t get any worse. But worsen it did.

Six months later, in May 2020, I was out of work and cooking in a comedor myself, and I messaged him asking if he could use twelve crates of a job lot of rapidly ripening bananas donated from Buenos Aires’ central market. He responded with photos of the scene outside UTEP: crammed with people, the street was a grim simulacrum of a fiesta, as if the whole barrio was resorting to the soup kitchen to fill their stomachs.

On the busiest days of the pandemic, his cooperative cooked over 6,000 portions in total, he said. “We were working almost 24/7… the cardboard recyclers came and pitched in,” he said, burying his face in his hands as he remembers. “It was the most terrible year for me.” Demand has stabilized at around 2,500 portions a day, more than double pre-pandemic levels, he says.

The question, now, is how - or whether - Argentina can pay off the IMF without hurting the most vulnerable, something that thigh-rubbing financial editorials are already taking as a given. While many fear that an agreement will be too harsh, leading to a default that would further hurt the population, financial observers believe the fund’s dovish new managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, could sign on to a deal that will not fix Argentina’s underlying issues.

Campaigners have a more straight-forward solution: don’t pay the debt. They argue that the IMF loan was taken out against the will of the people, and that far from maintaining essential public services, it was used to fund sketchy deals and capital flight. Before any of the money is returned, a careful audit should be conducted, they argue.

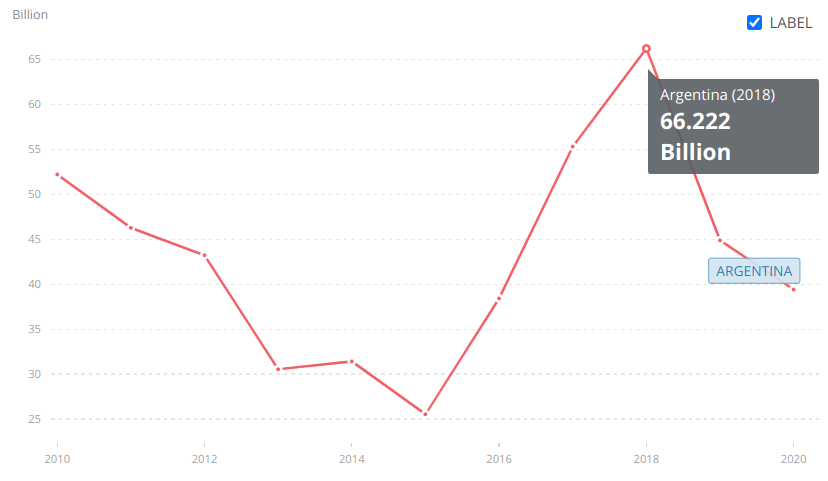

Argentina’s international reserves spiked to USD66.2 billion in 2018, the year of the loan, before plummeting to USD44.9 billion in 2019, according to IMF data. Macri recently said he had given some of the money to commercial banks so they wouldn’t leave the country. Critics immediately took this as an admission that he had violated the fund’s statutes by funding capital flight.

But more sympathetic observers said it reflected a need to provide a minimum of trust and stability in a national economy where nobody wants to hold their savings in the local currency. Either way, the government intends to pay to avoid becoming an economic pariah, a situation that would likely devastate the peso and tighten the screws on the poor anyway.

Whatever happens with the deal, the mood in Argentina is black. Many tell PWS they see no hope, just an ever-growing line at the soup kitchen’s doors. At the height of the 2001-2002 financial crisis, 70% of children were living in poverty. Today, that figure stands at 65%, according to a report published this week.

“[After a while doing this] you realise that comedores are transcendental for maintaining social calm,” Paniagua said. “[...] Those who end up suffering are always, always the excluded.”

Stories we’re watching:

The US Treasury imposed sanctions on top officials in El Salvador’s ruling party, including President Nayib Bukele’s chief of Cabinet. They are accused of illicit negotiations with gangs and corrupt handling of COVID-19 funds. Bukele responded by tweeting allegations that a US diplomat had pressured him to release a politician who was allegedly dealing with gangs.

In Cali, Colombia, the public prosecutor has charged 8 police officers with “torturing”, “arbitrarily detaining”, “discharging firearms at” and “threatening the lives of” protesters during the national strike in May. Eight civilians were also indicted for firing live ammunition at crowds of protesters as police watched without interfering. The government denied these events when reports first emerged.

Spanish words of the week:

Trámite (m) - A bureaucratic procedure or set of paperwork. Used for anything from a visa application to accrediting university modules. Think of it as a mixture of a form, a request, and a nightmare combined with a splitting headache.

Se lo murieron (Colombia) - When a protester or a political prisoner dies in the hands of the security forces, this phrase is used to imply that the deceased may have been helped along: “¿Se murió o se lo murieron?”