The Morning After in Venezuela: Perspectives on what comes next from Venezuelans

PWS sat down for extended conversations with three close contacts from very different parts of Venezuelan society to ask them their thoughts

Now that the dust has settled from US attacks on Venezuela, in some locations quite literally, we thought it might be a good moment to explain to our English-speaking readers what Venezuelans, both in Colombia and within the country, think of events over the last week.

To that end, we had in depth conversations with three longtime PWS contacts about their thoughts, their hopes, and anything they wanted people in the US or Europe to know about current events.

“Ulysses”, a journalist from Zulia, Venezuela, currently in exile in Colombia

Ulysses, who asked that his real name be withheld and a pen name he often publishes under be used instead, fled Venezuela in 2020 after being arrested by the intelligence service SEBIN.

SEBIN threatened to accuse Ulysses of espionage and “terrorism” under a law in Venezuela that allows the state to persecute those who criticize government actions. He views Maduro’s exit as a positive, and Venezuela’s future as a slow arc towards improvement. He also, however, is certain that many US analysts are getting some basic assumptions very wrong.

“I keep reading that the Chavista regime is going to fracture under US pressure,” he said. “I don’t at all believe that is true. They understand that in order to survive, they have to present a unified front.

Ulysses explained that while squabbling between competing interests is no doubt occurring in the background, top officials are looking at pragmatic responses to an unprecedented action.

“No [state] has ever kidnapped a sitting president,” said Ulysses. “Questions of legitimacy aside, Maduro was the effective head of state in Venezuela. The ‘rules’, as Chavistas understood them for two decades, no longer exist. It’s a new game. And they know they need to present a united front to survive it.”

Ulysses believes that the Chavista inner circle will adapt to new dynamics far better than most Western analysts believe. “The US is seeking a client state,” he said. “They’ve made that clear. But Chavistas understand completely what that means. And the one area where they do have a bit of leverage is that they’re the ones who know how to get things done.”

“There are, of course, some ideological reasons to resist US actions, but ultimately the bureaucracy in Venezuela is motivated by financial interests rather than political ones,” continued Ulyses.

“And that bureaucracy wants to continue holding the levers of power under whatever system develops in the future. These are people who have survived in a highly competitive and often cutthroat political environment, and they will employ those skills under whatever system ultimately shakes out in Venezuela.”

“Besides, as much as they criticize the US in public statements, they have all secretly wanted to do business with Uncle Sam. They are terrified right now, and angry, but also deeply curious,” he continued. “This is new territory all around.”

PWS: And if the US requires elections?

“Real, fair elections are not possible under current conditions. But I can foresee imposed elections in the next year or so. They would be imperfect at best. Let’s call them ‘elections’ in quotation marks. I think that scenario depends considerably on how conditions develop in the meantime. Is food more expensive due to lost oil revenue? Does stability decrease even further in peripheral regions of the country?”

“But even in a best-case scenario, if we imagine Chavismo losing a somewhat fair election to whoever ends up representing anti-Chavismo currents, the movement itself will survive. They have a shrinking, but solid base that will allow them to hold some governorships, seats in the Assembly, etc., etc. And they will take the defeat and work from there. They are highly adaptable. And especially if the current opposition over-promises on results, they will bounce back.”

PWS: Are US actions about oil?

“I wish I could take you to Tachira, Zulia, or Maracaibo. You’d say What oil? Where is the oil?’ Yes, Venezuela has the largest reserves on the planet, but the infrastructure is badly decayed. If the US wants to invest billions of dollars, it could eventually rebuild that infrastructure, and ‘steal’ the oil. But from my perspective, even understanding that there are a lot of unknown factors both domestically within Venezuela and in terms of investment guarantees that would have to fall into place for that to happen, such a system would be better than what we currently have.”

“You’re asking me to choose between two different systems of looting. I choose the gringo looting, because maybe then we at least get some infrastructure built. Venezuelans are pragmatic by nature. We know the gringos want to exploit us. But that’s a system we understand. It has happened in the past. We know what to expect when doing business with Uncle Sam.”

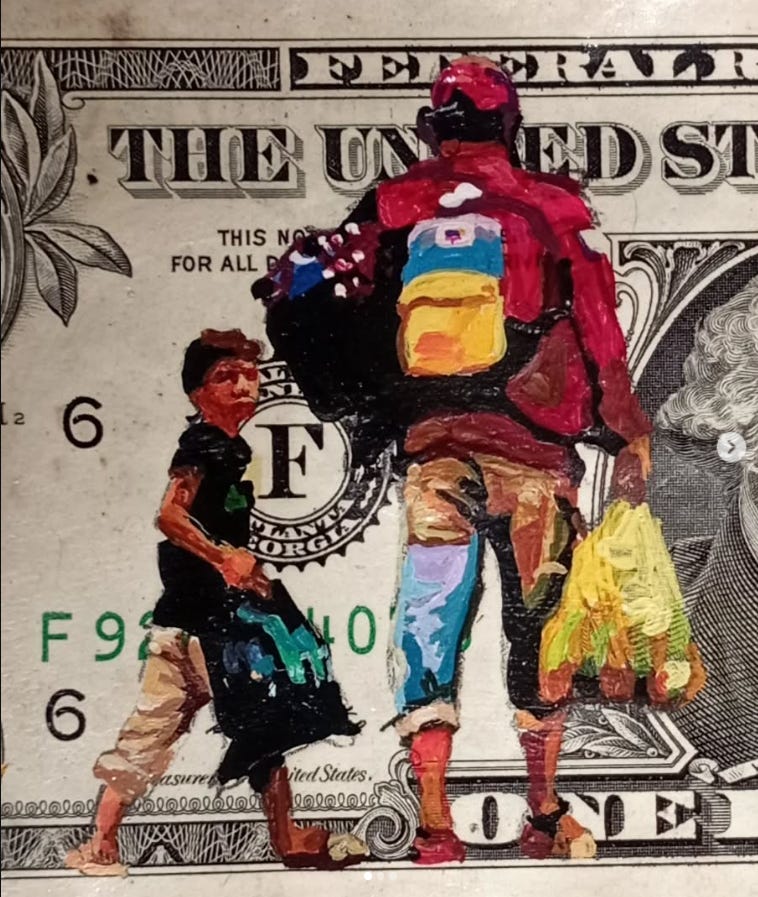

Javier José García and Paula Villamizar Guerrero, street artists in Medellin, Colombia, originally from Táchira, Venezuela

Javier and Paula work in the streets in Colombia, selling their art. In the past, they worked exclusively painting Venezuelan Bolivares, the currency of the country. But now they also do portraits, caricatures, and occasionally participate in original fine-art works for gallery shows.

They both crossed into the country informally in 2019 and lived in Bogota for two years before relocating to Medellin. They don’t describe themselves as highly ideological in terms of politics.

“I’ve seen the left shit itself in Venezuela,” said Javier. “And I’ve seen what violence the right has created in Colombia historically. I think people toss around this word ‘fascism’ a lot. Whatever you personally might mean by that word, I think of it as describing a government that is violent and authoritarian. And those actions can come from either side of the political spectrum. I don’t identify with either. The truth is, I’ve grown somewhat allergic to governments in general.”

When asked if US actions removing Maduro in Venezuela were a positive development for the country, Paula responded colorfully. We’ll leave it in the original Spanish because, honestly, PWS is not sure a translation can do it justice:

“Coño, como me vas a preguntar eso, marica!?”

“Of course it is,” she continued. “I hope that son of a bitch [Maduro] rots [in jail].”

“We watch what Trump is doing to Venezuelans in the US, and it’s terrifying,” said Javier. “Going back to my point above about fascism, I worry if maybe we’ve simply traded one dictator for another. But even acknowledging that, anything is better than what we fled.”

“It’s like a dictator-light, though, compared to Maduro,” said Paula. “I think a lot of people in the US see things getting worse. In fact, ICE reminds me of FAES [Venezuelan special forces police]. They even dress the same. But as bad as the direction the US is heading in, they still haven’t seen a full dictatorship. I think most people living there have no idea what that’s like.”

PWS: Are US actions about oil?

“I don’t know. Probably. I don’t care, though,” responded Javier. “I mean, fuck. Where is my oil? Do I keep it in the fridge? Is it under my bed? I don’t have any oil. It isn’t mine. Why would I give a fuck? Next question.”

Paula, laughing, added, “That doesn’t have anything to do with us. I think there is a perception among people in the US that we all have oil money. We don’t. To me, it doesn’t really matter who controls the oil [US companies or the Venezuelan government]. They’re all thieves. Thieves like to fight. I just want to go back and see my grandmother.”

Javier said he understands liberal resistance in the US to Trump’s actions, but says “we each weighed 19 kilos (roughly 40 pounds) lighter when we arrived in Colombia. Respectfully, I think most gringos have no fucking idea what it’s like to go hungry. Politics stop mattering so much when you’re suffering from real hunger.”

“Who exactly is stealing the oil doesn’t matter very much either in that case,” added Paula.

Andres, a recently graduated engineering student in Caracas

Andres asked that his real name be withheld as police in the capital have been reviewing social media of residents in random stops, and detaining anyone with messages expressing support for the capture of Maduro.

“They’ve also been going after individuals for posts they find online, if they can be traced back to a specific user,” he told PWS. “Crackdowns have everyone on edge; it’s a tense atmosphere in my neighborhood. No one knows what’s coming next.”

At first, he was in shock. When his city was bombed by the US military, he didn’t understand what was happening until many hours later. “We suspected it was the gringos,” he said. “But nothing was confirmed, and the rumor mill was running wild.”

The morning after, he was “of course happy that Maduro had been captured, but also still scared. Really, I still couldn’t believe what was happening,” he said.

“But I was also mad, initially, that [Vice President] Delcy [Rodriguez] had taken power, and that the Chavistas would continue. After considering it for a few days, though, I think it was the least bad option.”

Andres doesn’t believe that opposition figures could have run the country without everything collapsing or a bloody power struggle. “The only way that scenario could have worked would be if it were imposed forcefully,” he said, explaining that a full US occupation providing security in the capital and backing an installed government would have been necessary to fully change governments.

“And no one wants that,” he said. “Not Chavistas, not residents, not anyone, well, except maybe the opposition.”

He hopes that US pressure eventually leads to free elections, but in the meantime thinks that the current paradigm is workable. “At least it avoids civil war, or a guerrilla war against occupying Americans,” he said.

He is careful what he says in public, however, and told PWS he isn’t sure what his neighbors really think. “And the uncertainty hanging over the situation also makes everyone more cagey,” he said. “No one knows what food prices are going to look like in a month or a year. I think a lot of people are more concerned about that than they are about who is in Mira Flores,” he said, referring to the seat of government in Venezuela.

He isn’t at all a fan of Trump. “I don’t think he really cares about the Venezuelan people,” he said. “But maybe that doesn’t matter. I don’t know. I’m more interested in results than teams at this point,” he said.

PWS: Are US actions about oil?

“I don’t know,” replied Andres. “They seem to insist it was. That seems very removed from my daily life, though. I don’t really think much about that. I’m more worried about the immediate future. I think this could be good, if the gringos can force Delcy to make some concessions.”

“I think more about political prisoners than oil,” he said. “I have friends in jail for protesting, or who were arrested and detained for messages they sent. That’s honestly a lot more on my mind than PDVSA (Venezuela’s state-owned media company).”

PWS: Is there anything you wish people in the US knew about what’s happening?

“I wish that US leftists would express more support for the Venezuelan people, rather than the government,” he replied. “I see a lot of abuse,” in both public statements as well as on social media.

“I’m a leftist,” said Andres, “and I think [leftists in the US] are really undermining themselves when they cheer on people who have arrested my friends, committed torture, and extrajudicial killings.”

“I like to think a lot of this comes from people who instinctively distrust US actions in the past,” he continued. “Like Iraq, or Afghanistan. Or people who are from marginalized communities and have felt the structural violence of US actions.”

“I understand both positions,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean you have to support a government that is in many ways leftist in name only,” he said.

“We really have more in common,” materially speaking. “I think they are confusing solidarity for a state with solidarity for a people. And that’s really a shame,” he said.

“I’ve really personally gotten much more solidarity from Iranians and Palestinians online than I have from people in the US,” he said. “There are exceptions, of course, I’m just speaking generally.”

“I guess if I could tell them one thing, it’s that reflexive support for a state you know little about is dangerous, no matter what country we’re discussing.”

You can also donate a one-time gift via “Buy Me a Coffee”. It only takes a few moments, and you can do so here.

And if you can’t do any of that, please do help us by sharing the piece! We don’t have billionaire PR teams either.

Hasta pronto, piratas!