Urban Legends and a media-ecosphere: How the "Tren de Aragua's" infamy grew across the Americas

Dishonest politicians, paranoia, xenophobia, and a lack of real research have affected even well-meaning commentators

The Tren de Aragua— the so-called “super gang” that evolved in prisons in the Venezuelan state by the same name — has become a boogeyman of the western hemisphere in recent years.

As the Venezuelan diaspora continues to grow (nearly 8 million people have fled the South American country since 2015) xenophobia in the region has increased alongside it.

Reports of ‘Tren’ brutality and their supposed overwhelming power have become ubiquitous in media reports from across the continent, most recently in the United States.

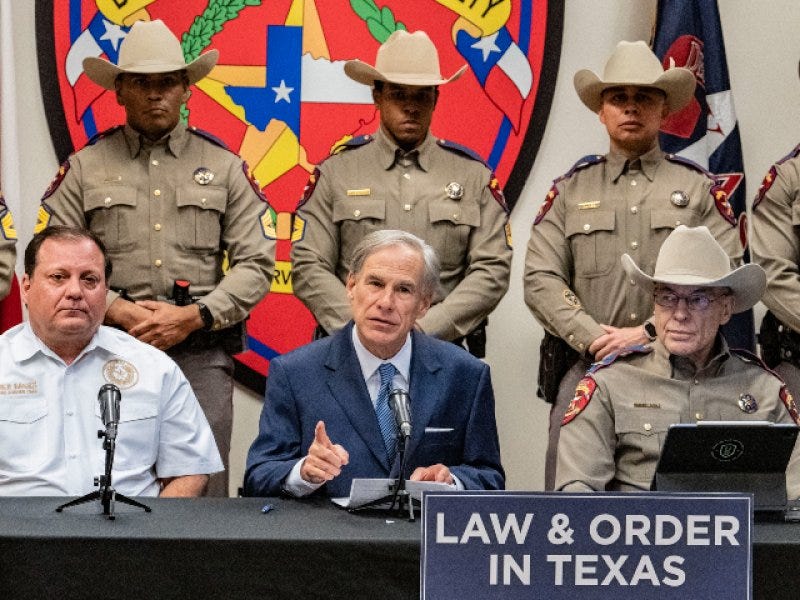

Politicians across the Americas have been eager to falsely blame migrants for high crime rates, or invoke the name of the ‘Tren’ to inspire fear among voters and build support for police crackdowns and anti-migration policies.

Irresponsible or sensationalist media companies have been eager to repeat these claims, often without bothering to check if they are true— reports repeated by other media companies until, eventually, a narrative of terror takes hold in the popular imagination. A legend begins to take on a life of its own.

As elections approach in the United States, the Tren bogeyman has reached a fever pitch. False reports on social media about the presence of the Venezuelan criminal group there have gone viral, despite being disproved by authorities in the very cities these supposed incidents took place.

So who are the Tren de Aragua? Do they have a presence in the United States? Are they a “transcontinental terrorist organization” as Texas Governor Greg Abbot recently claimed? Have they overrun South American countries like Colombia, where nearly 3 million of the Venezuelan diaspora currently live?

In a word, no. At least not as the story is usually told both here in Colombia as well as by English-language media and North American politicians. Although they do operate across countries, especially near land borders in South America where immigration is common, and there are certainly members (or ex-members) that form part of an international community now nearly 8 million strong, they do not have anywhere near the power, coordination, or presence that many “experts” so often quoted by media suggest.

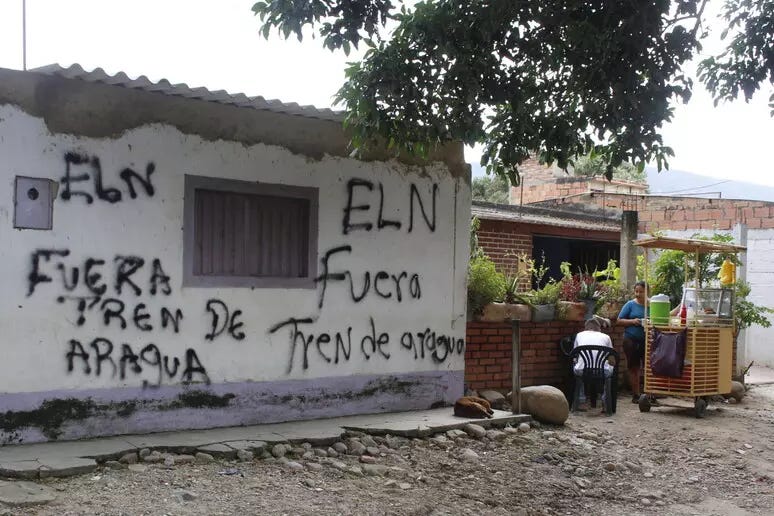

The ‘Tren’s” disastrous war with Colombian organized crime in the borderlands

But before we get into the details, (and the receipts), I want to tell a story about 2019, the year I first heard of the “Tren”. I think the context will help you understand a bit more about how the Tren de Aragua works, and why their attempted expansion into Colombia was an utter, and very bloody, failure.

For almost three years at the height of the Venezuelan exodus, I lived and reported on the Venezuelan-Colombian border from Cúcuta, Colombia. During that period, smuggling of all types going both ways across the borderlands peaked: an illicit activity that generated millions of dollars for the criminal groups that controlled it.

Those profits also generated a shadow war as leftist rebel groups in the region, such as the National Liberation Army (ELN) clashed with paramilitary criminal groups and narco-traffickers to control an increasingly lucrative trade.

I’ve written a lot about this dynamic over the years, both here at PWS and at the media companies I freelance for. My beat was the border, and in those days, the border was violent.

A turf war at the time between the Rastrojos, a Colombian paramilitary criminal group who rose from the ashes of right-wing death squads that fought on the side of the Colombian government during the country’s civil war, and leftist ELN rebels was waged murder-by-murder in the hundreds of trochas, or smuggling trails, that honeycomb the region around Cúcuta.

During this period I also covered the Venezuelan side of the borderlands for international media. Tales of the Tren de Aragua, even then, were common, as was coverage of their expansion within Venezuela, but their power center was half a country away, near Caracas on the Atlantic coast of Venezuela.

They did, however, eventually arrive in Cúcuta, lured, like the Rastrojos, to the region by colossal black market profits in a largely lawless border region rife with smuggling. By then the Rastrojos had been eliminated by the ELN, and an uneasy truce had taken hold between the rebel group, who controlled rural areas around the city, and paramilitary and narco groups, who (for the most part) controlled Cúcuta itself.

At first, Tren members worked largely on the Venezuelan side of the border selling “travel packages” to the hundreds of thousands of migrants leaving Venezuela for other parts of the Americas. Small groups of the Tren would provide “guaranteed” travel to countries like Chile, Peru, Ecuador, or Panama that included guides on each border migrants crossed informally.

But it didn’t take long for some Tren members to attempt stepping into turf firmly controlled by much more established (and experienced) Colombian organized crime groups.

Some attempted to extort businesses in the areas at the main land crossings near Cúcuta. Others tried to set up prostitution rings within the city itself. This created another wave of violence as Colombian criminal organizations retaliated, and to borrow a U.S. military euphemism, they did so with “extreme prejudice”.

In La Parada, the community at the foot of the Simon Bolivar Bridge that stretches from Colombia to Venezuela, a man who claimed to be from the Tren began trying to extort restaurants and shops that were already paying “protection” to Colombian criminal groups. He was disappeared, as was his romantic partner, and all of his associates. No trace of them was ever found.

Tren members ambushed the guides who charged migrants to cross ELN-controlled trochas near the community of Juan Frio. The next day a plastic trash bag of severed heads of Tren members was found near the exit of the smuggling trail, placed intentionally where it would be found.

These are just concrete examples I witnessed personally. The Tren de Aragua, unused to real resistance in Venezuela, expected to find territorial acquisition easy in Cúcuta. They were wrong. Eventually, they negotiated an uneasy truce with Colombian groups, agreeing to stay in Venezuelan territory or small communities in the Colombian shanty towns that dot the borderlands.

False claims in Colombia, Chile and Peru

But this same dynamic has played out across all of Colombia. The Tren de Aragua has been unable to establish any territorial control. An in-depth investigation by La Liga Contra del Silencio, an investigative journalism group in Colombia, showed that members of the Tren, unable to compete with organized crime in the country, often end up working as low-level employees for those organizations instead.

They are “ “the disposable cannon fodder” for Colombian organized crime groups, one gang leader in Bogotá told La Liga. If they are killed, or arrested, he said, “I will just hire another.”

According to the same investigation, some migrants, desperate for work and staying in shelters they must pay for by the day, will lie about being members of the Tren de Aragua in an attempt to obtain low-level jobs micro-trafficking drugs or as enforcers for Colombian organized crime groups.

Yet the fearsome reputation of the Tren has grown in Colombia, in no small part due to false statements by politicians and security forces, who are eager to blame them for decades-long and very homegrown problems with organized crime, as well as petty street crimes.

In no small part because of that infamous reputation, small-time Venezuelan criminals in Colombia who have nothing to do with the Tren have even claimed they work for the organization in an attempt to intimidate residents or threaten other criminal groups.

Bogotá’s former mayor Claudia López, who while in office often made false claims about Venezuelan migrants being criminals, insisted police launch a special operation to “dismantle to Tren de Aragua” in the city.

As part of those investigations, she repeatedly claimed that Venezuelan migrants arrested for muggings formed part of the organization— claims which Colombian police publicly denied.

Although per-capita crime committed by Venezuelan migrants in the country has risen since 2017, they still commit crimes, particularly violent crimes, at a lower rate than natural-born citizens across all Latin American countries.

So if the data, the experts actually doing the legwork on the ground, and even the police agree that the Tren de Aragua has a limited presence in Colombia, how have legends of their brutality grown into a hemispheric phenomenon?

An echo-chamber that affects even professionals

In no small part, it is due to the inherent biases of even responsible media companies. Large media companies, as a whole, tend to over-rely on “official” sources like government officials, corporate think tanks, and retired “experts” who purport to speak for law enforcement but have been removed from the field for years if not decades, and this bad reporting has been mistaken as consensus by even well-intentioned people covering the story in the U.S.

For example, in a recent AP piece, Joshua Goodman, writing from Miami, quotes comments by ex-DEA agent Wes Tabor, who has been retired since 2012, as evidence of Tren de Aragua's presence in the U.S.

“They’re aggressive, they’re hungry and they don’t know any boundaries,” says Tabor in the piece. “They’ve been allowed to spread their wings without any confrontation from law enforcement until now,” he continues, referring to efforts by some politicians to declare the Tren a terrorist organization.

Tabor presents no evidence for his claims and cites no examples. To be fair to Goodman, he goes on to bring up examples of false claims that have gone viral in the U.S. as well, like the Tren taking over apartment buildings in Aurora Colorado., a story that has been disproven.

But he also cites claims by local police in Texas and New York, also presented without evidence, that some arrestees who have been detained by police are suspected Tren de Aragua members.

At this point, I would like to stress, strongly, that claims made by police without evidence are not to be trusted. Police lie to the media. A lot. The National Criminal Justice Association, which is an advocate for a fair criminal justice system in the U.S., calls the practice “incredibly common.”

In addition to outright dishonesty, police have their own confirmation biases. A beat officer, untrained in real investigation techniques, who has been flooded with messages from politicians spreading falsehoods that “Venezuela is sending its criminals to the U.S.” might even really believe, despite a lack of any evidence, that any male Venezuelan migrant between the age of 18 and 35 is part of the Tren.

That doesn’t make it true.

Insight Crime, another media company that usually does an excellent job, in an article with no byline or datelines, falls into this trap as well. Our anonymous author, writing from God-knows-where, writes:

“Although authorities’ methods of identifying Tren de Aragua members or their links to the wider organization remain unclear, reports of alleged Tren de Aragua activity have arisen in at least ten US states. Cases in Colorado, Texas, and New York have received prominent attention, alongside others in Illinois, Florida, Louisiana, Indiana, Georgia, Virginia, and New Jersey.”

The author admits that no evidence has been presented, at least publicly, in any of these cases. The article goes on to refer to migrants suspected of being Tren members by local police as “cells”, a term usually reserved for organizations like ISIS or Al Qaeda, before finally admitting in the last paragraph of the piece that “Authorities have also not revealed any proof” of the allegations the writer spent the entire article discussing.

There is also no evidence, despite claims by ex-president Donald Trump on the campaign trail, that “Maduro is sending his criminals to the United States”.

In a diaspora of 8 million people, there are certain to be some bad actors, just like with any large group of people. There are certainly members and ex-members of Tren de Aragua within that population.

But the “supergang”, despite their strength in Venezuela, has very little coordinated and organized presence in even Latin American countries. They have even less in the United States.

At PWS we urge our North American brethren to recall that election season often brings out the worst among politicians and social media users, but that ultimately, the burden of proof rests with those making a claim.

The Tren de Aragua does indeed commit horrific crimes, mostly within Venezuela, but across the continent as well. But in this case, urban legends have affected the judgment of even well-meaning journalists and “experts”, and the narrative has taken on a life of its own.

Their reputation far exceeds their capabilities.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Mexican soldiers killed 6 migrants and wounded 10 more after they opened fire on a group of people in a vehicle near the Guatemalan border. Soldiers claimed they heard explosions and fired on the vehicle, which fled the gunfire.

After a pursuit in which soldiers continued to fire on the vehicle “in an attempt to stop it”, according to Mexican officials, the driver crashed on a dirt road. According to the Defense Ministry, the migrants came from Egypt, Nepal, Cuba, India and Pakistan.

Mexican security forces have been under pressure from the United States to crack down on migration in the region. Many of the migrants killed suffered gunshot wounds to the back and head, suggesting they were no threat to the soldiers firing on them.

Claudia Sheinbaum was sworn in as president of Mexico on Tuesday. She is the first woman in the country’s history to hold the office, and also the first president of Jewish descent. She succeeds López Obrador (AMLO), who boasted historically high approval ratings in the country, but who at times proved controversial in his dealings with feminist protesters, and greatly expanded military power in Mexico.

Sheinbaum has promised to largely continue his policies, citing what she said were his economic achievements in the country. She faces growing insecurity in the country and the rising power of criminal armed groups.

The Dominican Republic announced this week it will begin mass deportations of Haitian migrants. The country, which shares an island with Haiti, has said plans include exporting 10,000 Haitians a week. The decision comes despite a United Nations statement calling for countries to halt deportations to the crime-stricken country amidst a massive surge in gang violence.

Meanwhile, a gang attack on a Haitian town on Oct 3, killed at least 70 people At least 3,000 people were also displaced when the “Gran Grif gang” used automatic weapons to fire on residents of Pont-Sond, about 100 km northwest of Port-au-Prince, according to statements by U.N. officials.

Spanish word of the week

Dominadas (fpl) - pull-ups. Amy’s hand-stands teacher was talking about “dominadas” for breakfast and she assumed it might be some kind of pastry, or perhaps a kink of some sort, Boy, was she in for a surprise, and perhaps some minor disappointment as well.

Thanks for reading and supporting PWS. Hasta pronto, piratas!

Good article, cheers