U.S Foreign Policy a key factor in record numbers risking their lives in the Darien Gap

A strategy to reduce arrivals at the border hasn’t worked, but it has put more lives at risk

This is an installment of the “Ship’s Log” series, more personal entries on the beats we cover for paid subscribers.

If you haven’t signed up for a paid subscription, we urge you to consider doing so. We have plans that start at just $5/month and the resources help us continue bringing you the stories that most big media companies miss.

If you have, thank you, and read on!

Well before dawn, sirens began to blare through loudspeakers. Immediately afterward, the sound of a few crying children, startled from sleep, filled the previously tranquil and humid night at the migrant camp just a few miles from the Panamanian border where I had spent the night.

Hundreds of migrants, the vast majority with dreams of entering the United States, emerged from their tents in the darkness and began to prepare for the dangerous multi-day hike through the jungle land crossing between Colombia and Panama— the Darien Gap.

Record numbers crossed the Gap last year, more than half a million people, and 2024 numbers will likely exceed that. There are numerous reasons for increased migration globally: political instability, climate change, and climate disasters, a trend towards authoritarianism, and battered post-pandemic economies.

But policy crafted in Washington D.C is the prime factor in why so many are forced into the most dangerous land migration route on the planet.

Up until recently, the Gap, with mountainous dense jungle terrain that famously crushed engineers' dreams of ever completing the Pan-American Highway, was described with words like “impenetrable”, “uncrossable”, “deadly” and “treacherous”.

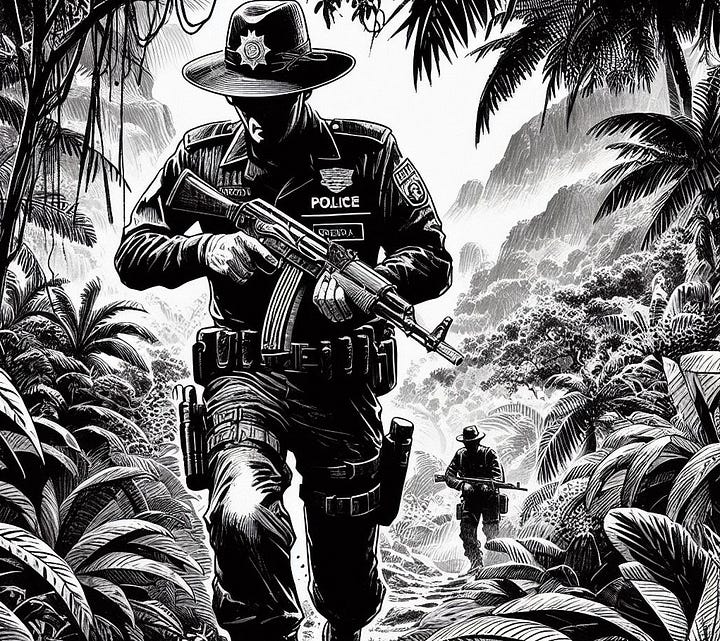

In Spanish it’s called the Tapón de Darién— a word that means “a plug”, or a “stopper”, as in a corked bottle of wine. The Darien is still deadly for some and utilized (on non-migration paths) by armed groups, smugglers, as well as local gangs from the communities who have always called the Gap home but it is no longer a tapón.

“That’s the impression the U.S wants people to have, of the Darien, that it’s blocked, too dangerous to cross,” a U.N aid worker in the region who asked that his name be withheld told me. “But there is no tapón. Not anymore. The Darien is open for business.”

That business, however, is dominated by international criminal groups who also use the gap for smuggling cocaine, weapons, and extortion.

Policies of state neglect in the region by the Panamanian and Colombian governments, and the quiet refusal of security forces to take even minimal actions against criminal groups in the region, allegations of violence, robbery, and sexual violence don’t seem to make intuitive sense at first glance.

But ignoring the humanitarian crisis, and the illicit economies that profit from it is preferable from their point of view than being accused by the U.S. (and perhaps their domestic political opponents as well) of facilitating migrant passage through the dangerous corridor.

The Colombian state, long absent in the region, seems content to leave the administration of the Gap to AGC, the biggest criminal armed group in the country. Panama is strict about granting journalists access to the processing camps for migrants on their side of the border and is even banning some humanitarian organizations from providing treatment there.

Meanwhile, U.S. diplomacy in Central America has been focused on other forms of deterrence as well. Mexico has been happy to oblige the Biden administration with deportations from Mexico, police attacks on migrant caravans and camps, as well as accepting migrants expelled from the U.S. who have been denied their legal rights to asylum processes.

Washington has also repeatedly pressured Mexico to put a cap on migrant numbers entering through their shared border with Guatemala.