Why virtually all child sex crimes in Colombia go unpunished

Lack of coordination and political will allow impunity for abusers

This week we’re proud to welcome back Adriaan Alsema, executive editor of Colombia Reports, for a guest feature here at PWS.

Colombia’s government and judicial authorities have failed to implement policies to reduce widespread sexual violence against children, a practice that systematically fails to protect children, and incentivizes their abusers.

For decades the government has failed to develop strategies that would allow officials, scholars, or activists to collect the data necessary to paint an accurate picture of child abuse and exploitation.

Children and parents seeking justice for sex crimes are more often than not revictimized multiple times because of the lack of coordination between government bodies and employees, for example, prosecutors and social workers.

Consequently, vast numbers of victims abandon their quest for justice, which in some cases may take more than a decade, said the executive secretary of NGO Alianza por Los Niños (Alliance for the Children), Angelica Cuenca.

How serious is the situation?

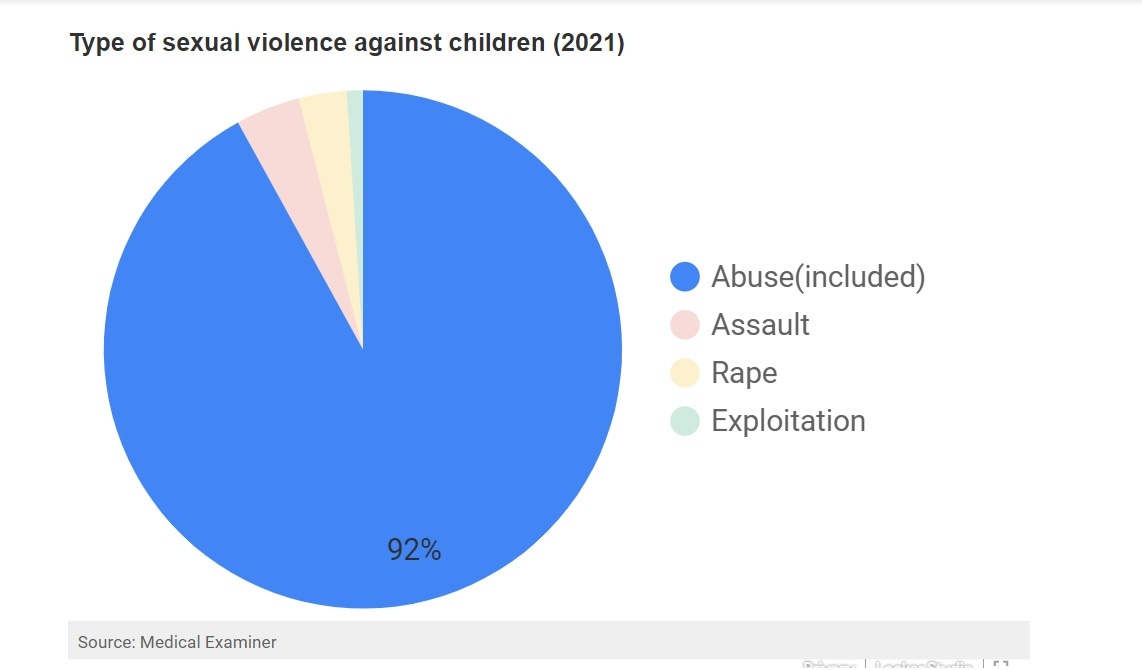

Between 2018 and 2023, the Medical Examiner’s Office examined 119,324 children and minors who were allegedly the victim of sexual violence.

In a report that was published in December last year, Alianza por los Niños said that more than three-quarters of the reported cases of sexual violence in 2021 occurred at the child’s home.

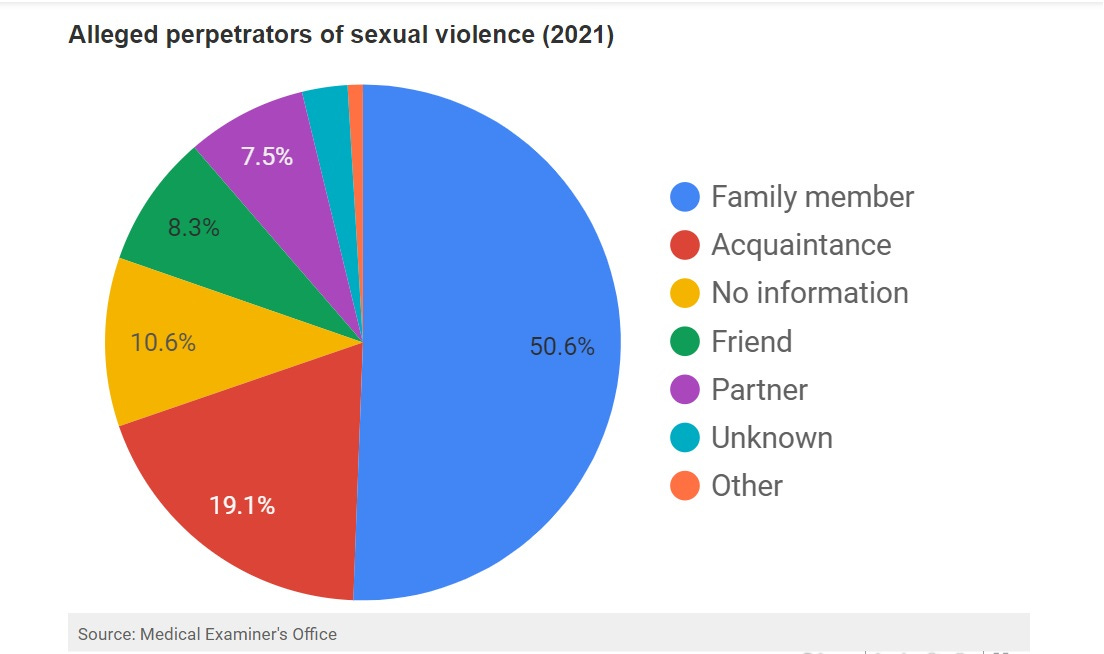

The alleged perpetrators were family members of the victim in more than half of the cases that ended up with the Medical Examiner’s Office.

Impunity for sexual violence against children

According to the Prosecutor General’s victim database, only 1,389 people were convicted for sexual violence against children since 2018.

This is less than two percent of the children examined by medical professionals because of alleged sexual violence in the same period.

The real number of victims is likely much higher than the one registered by the Medical Examiner’s Office because of underreporting of sexual violence.

This is particularly an issue in areas where State authorities have historically been absent and in cases of sexual exploitation, which often is not reported.

Chaotic State approach

How many child victims of sexual abuse there really are is anyone’s guess as the information authorities collect is incomplete, and rarely shared between agencies, according to Alianza Por Las Victimas.

For example, the number of underage victims of sexual violence attended by the family welfare agency ICBF between 2017 and 2022 is half the number of victims registered by the prosecution, the NGO stressed in its December report.

This lack of communication between the multiple institutions effectively contributes to impunity for perpetrators.

In many cases, victims abandon their quest for justice because they have to repeat their account of the allegedly committed sex crimes multiple times.

Another major issue is the time that it takes for law enforcement or the judicial branch to respond.

Reports by Alianza por la Niñez and the Ombudsman’s Officer show that the prosecution in some cases needs more than a decade to call a suspected child abuser to court.

According to Cuencas, victims are often removed from their homes by relatives or friends due to the time it takes to impose official protective measures that would keep their alleged victimizer away.

Despite repeated calls for action, authorities have yet to come up with reforms that would allow an effective approach to prevent or prosecute sexual violence against children.

A recent case in Medellin, in which 36-year-old Timothy Alan Livingston, from Ohio, was found in a hotel room with two children, inspired widespread outrage in Colombia. Livingston fled the country before charges could be filed.

He joins a long list of alleged child abusers who have discovered impunity for their crimes. Petro has requested his extradition, an unlikely outcome.

Medellin needs to address sexual tourism in the country, which is a real problem.

But if Colombia really wants to protect child victims of sexual abuse, it needs better coordination and transparency between government agencies, prosecutors who investigate victims instead of ignoring them, and a deeper look at the numbers— which shows child abuse is far more likely to be intra-familiar than at the hands of a stranger.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Two mayors in Ecuador have been gunned down in as many days as the government’s “tough hand” anti-crime strategies continue to fail to stop rising violence.

We predicted this when Ecuadorian President Naboa implemented copycat El Salvador policies in January.

Jorge Maldonado, the mayor of Portovelo, "fell victim to gunshots that resulted in his death," police said on X, formerly Twitter.

More than a dozen politicians have been killed in less than a year and a half, including residential candidate Fernando Villavicencio, who was gunned down last August after leaving a campaign event.

Colombia’s capital, Bogota, has joined the list of mega-metropolises in Latin America that are on the verge of running out of water. As the city’s reservoirs run dry, officials have declared water rationing.

Mexico City is currently under similar measures. The shortages are caused immediately by extreme droughts caused by El Niño weather patterns in both countries, poor water management by officials, and decaying infrastructure.

But as climate change batters communities near the equator hardest, extreme weather events like drought and flooding will only become more common.

Ship’s Log

Joshua spent the last ten days crisscrossing Colombia’s northern borderlands with Panama as part of an in-depth investigation into the dynamics of the Darien Gap. The trip included sleeping at migrant camps and walking into the Gap itself with thousands of those headed north— principally with hopes of entering the U.S.

Despite being utterly cooked by the Caribbean sun, it was an incredible voyage that took him from the coastal towns that serve as the staging area for migrants headed to the Darien, towns controlled by armed groups near the Panamanian border, and the vast stateless areas that migrants must traverse to reach migration officials in Panama itself.

He has a lot of stories on the way with several media organizations, including a series on the phenomenon at the New Humanitarian.

Daniela has been freelancing in Bogota for El Pais and enduring the ongoing water rationing that the city seems likely to face in the near future.

Spanish Word of the Week

No le llegan ni a los talones

Literally translated, this phrase means he/she doesn't even reach the other person's heels in comparison. But it’s often used to mean something like the English phrase “Doesn’t even hold a candle to”, meaning one of the objects is so inferior that it doesn’t even merit comparison to the other.

I like this phrase. It implies that two people can’t be measured head to head because one can’t even reach the ankles of the other.

Seems a lot cooler than holding candles!

We can use it in an example sentence:

Otros medios de comunicación no le llegan ni a los talones de PWS- Other media companies can’t hold a candle to PWS

And no wonder! They can’t even reach our ankles.

Hasta pronto, piratas!