A brief history of EZLN: the Zapatistas in images

A photo essay and explainer, from inside the EZLN Autonomous Zone

Our own Daniela Diaz visited a Zapatista community inside the EZLN autonomous zone in Tenejape, Caracol Jacinto Canek, in the state of Chiapas, Mexico. This week’s feature piece is photo essay of her work inside the community, alongside a very brief history and explainer on the Zapatista movement. It’s exactly the kind of exclusive content we love producing and hosting at PWS

The mountainous forests of Chiapas have been stained by the blood of the indigenous people who have lived there for centuries. The Mexican state, through both outright violence as well as neglect, has eradicated entire communities.

These are not tales from a distant past, but rather the late 20th century. The Mexican army drove them further up into the mountains while ignoring outbreaks of tuberculosis, typhoid, cholera, measles, tetanus, pneumonia, and malaria as late as the 1990s.

In the 1980s, Mayan communities allied with Anarchist and Marxist activists exiled from urban areas in the country. They shared a common enemy — a federal government that was wiping them out.

After years of painstaking organizing, the predominantly Mayan communities formed the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) and rose up in 1994, declaring war on the Mexican state, 'not to usurp power, but to exercise it’, they said, ‘and to give voice to the voiceless’.

For 12 days, they skirmished with Federal forces, briefly taking towns, liberating documents, and spreading their message in the form of pamphlets, literature, and speeches.

The response by the Mexican government was incredibly violent and drew widespread condemnation from the international community and human rights groups alike.

Their spokesman at the time, Subcomandante Marcos, explained the motives of the revolution as multi-faceted, but one of its principal drivers was massive land inequality.

In 1990, 6,000 of Mexico's most prosperous dynasties owned nearly 3,000,000 hectares of the available terrain in Chiapas, almost half of the land in the state.

At the same time, nearly a million mostly indigenous villagers eked a living on the remaining land, only 41% of which was even remotely suitable for farming. Subcomandante Marcos writes in his memoirs of the uprising: 'This is what capitalism leaves us as payment for everything that it has robbed us of.'

Following the rebellion, the Zapatistas declared a large section of Chiapas an EZLN “Autonomous Zone”, and though the Mexican government doesn’t officially recognize it, the land is managed by local communities who forbid state security forces from entering.

Western writers, academics, and popular culture have always had difficulty describing the politics of the Zapatista movement. Is it Anarchism? Is it Marxist? Is it indigenist?

It is perhaps understood best as a synthesis of Anarchist ideas of direct democracy and indigenous traditional governing systems from the region — based on community councils made up of rotating representatives and independent villages acting as a loose federation.

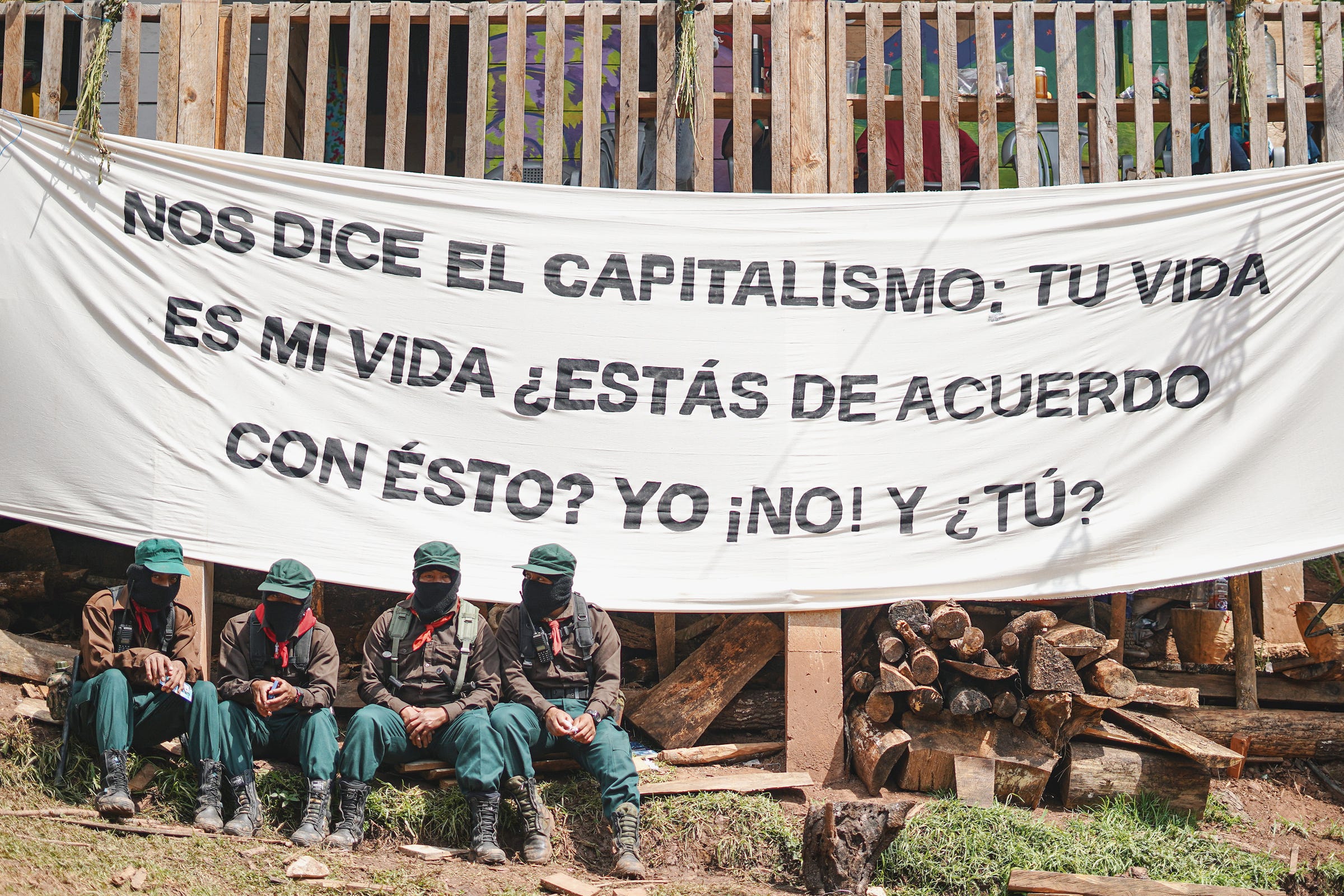

The Zapatistas wear masks whenever interacting with the outside world in part due to safety concerns about a state that has often persecuted them. The iconic baklavas have also, however, become an integral symbol of their revolution.

They have been described at different times by members of the community as “a rejection of traditional representative politics and individual identity in favor of direct democracy, equality and to undermine hierarchy and authoritarianism.”

They have also been explained as “a way to ensure we are seen, and invite others to our struggle.”

The Zapatistas reject state sovereignty and completely reject capitalist and liberal market-based representational republics, believing they are irreparably tainted and democracy in name only. They refer to such state systems as oligarchies, or, in an even more derogatory form, as “Democracy, Incorporated.”

However one chooses to categorize Zapatista governance, it is firmly grounded in breaking down decision-making to a hyper-local level and allowing the citizenry a direct voice in the process.

Visitors to autonomous zones in Chiapas must obtain permission from the communities to enter, and in the years immediately following the revolution they largely shunned the outside world.

In recent years, however, they have opened up more to visitors, journalists and the general public alike. They have also largely transformed from a militant movement into a bottom-up political one.

After centuries of genocide, war, economic exclusion, exploitation, and legal persecution, the predominantly Mayan communities that live in the EZLN autonomous zone finally achieved a real measure of self-governance, and they intend to keep it.

When PWS visited, one flag behind a group of Zapatista community members summed up the attitude of the community succinctly: “Capitalism tells us, ‘your life is my life.’ Does this seem like an agreement? To, me, no! To you?”

Text by Joshua Collins

The Big Headlines in LATAM

In case you missed it, PWS launched a new daily newsletter this week that brings flash updates on breaking news and fresh angles on the big headlines 5 days a week, Monday through Friday.

This is in addition to, and separate from, our weekly features. If you haven’t yet, you should sign up.

This week, we covered how leftist leaders are split over Daniel Noboa's election victory in Ecuador. Petro in Colombia refuses to recognize the right-wing incumbent. Sheinbaum in Mexico equivocated but will not renew relations with Ecuador after a previous split over Noboa’s decision to send police into the Mexican embassy in Quito.

Boric in Chile and Lula in Brazil offered their congratulations.

El Salvador was all over the news this week, with various stories about CECOT and the battle currently underway in the United States over Venezuelan and Salvadoran men deported by the U.S. to the infamous prison — and the largest such facility in the world.

We explained how El Salvador became the prison capital of the world, with 1 in 57 residents behind bars. We also broke down how the controversial photo-op of the meeting between Maryland Sen. Chris Van Hollen and Kilmar Abrego Garcia illustrates the carefully manicured imaging and stage-managing that characterize Bukele’s rule in El Salvador.

What we’re writing

This week for Mongabay, Daniela and Joshua published a long-read on Sheinbaum’s about-face on renewable energy in Mexico. A massive new Liquid Gas megaproject has inspired protests even among her supporters, who demand that instead of doubling down on fossil fuels, she fulfill promises to invest in solar and wind.

Spanish word of the Week

More of a Spanish paragraph: This is part of the message the Zapatistas released in 1994 when they declared war on the Mexican state, first in Spanish, and then in English:

Somos producto de 500 años de luchas: primero contra la esclavitud, en la guerra de Independencia contra España encabezada por los insurgentes, después por evitar ser absorbidos por el expansionismo norteamericano, luego por promulgar nuestra Constitución y expulsar al Imperio Francés de nuestro suelo, después la dictadura porfirista nos negó la aplicación justa de leyes de Reforma y el pueblo se rebeló formando sus propios líderes, surgieron Villa y Zapata, hombres pobres como nosotros a los que se nos ha negado la preparación más elemental para así poder utilizarnos como carne de cañón y saquear las riquezas de nuestra patria sin importarles que estemos muriendo de hambre y enfermedades curables, sin importarles que no tengamos nada, absolutamente nada, ni un techo digno, ni tierra, ni trabajo, ni salud, ni alimentación, ni educación, sin tener derecho a elegir libre y democráticamente a nuestras autoridades, sin independencia de los extranjeros, sin paz ni justicia para nosotros y nuestros hijos.

Pero nosotros HOY DECIMOS ¡BASTA!

We are the product of 500 years of struggle: first against slavery, in the war of Independence against Spain led by the insurgents, then to avoid being absorbed by American expansionism, then to enact our Constitution and expel the French Empire from our soil, then the Porfirian dictatorship denied us the fair application of Reform laws and the people rebelled by choosing their own leaders. Villa and Zapata emerged, poor men like us, we who have been denied the most elementary attention so that they may use us as cannon fodder and plunder the riches of our homeland without caring that we are dying of hunger and curable diseases, without caring that we have nothing, absolutely nothing, no decent roof, no land, no work, no health, no food, no education, no right to freely and democratically elect our authorities, no independence from foreigners, no peace or justice for us and our children.

But we TODAY SAY ENOUGH!

Thanks as always for reading. Hasta pronto, piratas!