Democracy is on the ballot in Guatemala

Corruption and links between organized crime and politicians would make a "Bukele approach" a nightmare

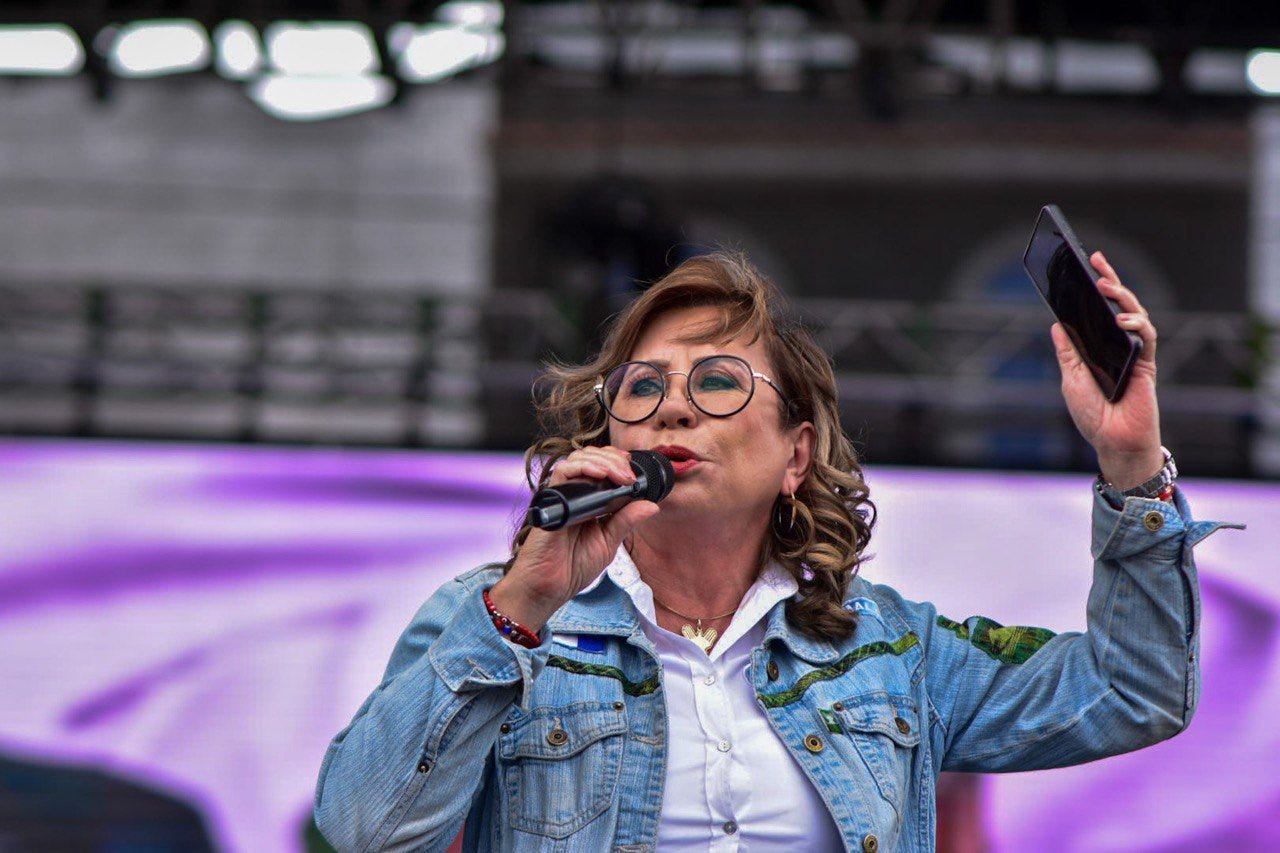

Guatemalans head to elections Sunday for the second round of a presidential election that has been plagued by controversy and anti-democratic interference by establishment elites. Dark horse candidate Bernardo Arevalo, a center-leftist who has run an anti-corruption campaign, squares off against Sandra Torres, a former first lady representing the National Unity of Hope (UNE).

Not only will Guatemala’s democratic institutions meant to protect the voting process will be tested, but the election is also a referendum on autocratic backsliding. Torres has vowed to implement a series of Bukele-style crackdowns on civil society should she win.

The most recent polls show Arevalo considerably ahead, but polls have been wrong before— such as when Arevalo surprised observers on June 25 when he emerged from relative obscurity to take second place.

After Arevalo beat out several other right-wing candidates, some of them claimed fraud without any proof. In the following days, the Organization of American States (OAS) reported no widespread irregularities, and the result was finally upheld by Guatemalan election officials.

On the same day however, Guatemala's Attorney General filed a legal challenge to bar Arvelo’s party, Movimiento Semilla, from participating in the election, which was upheld by lower courts packed with right-wing appointments. Prosecutors alleged that signatures from the party’s election registration forms had been fraudulent.

A higher court eventually struck down the decision after heavy international criticism from rights groups that called the move an attack on democracy itself.

The Attorney General’s office, undeterred, repeatedly raided the offices of Movimiento Semilla, as well as the offices of magistrates who struck down the ruling that would have barred Arevalo from running.

Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal ultimately filed an injunction against the AG’s office preventing further such actions to preserve election integrity.

The country has long been plagued by rampant corruption. Since military rule ended in 1986, Guatemala has been struggling to build a true democracy. Powerful groups — including former military, economic and political elites, and organized crime figures — have dominated the political landscape by building coalitions that often shield and facilitate their illicit activities.

Sandra Torre’s party has been the subject of multiple corruption investigations, and Torres herself was arrested in 2019 for campaign finance violations and false accusations of political opponents.

The country's attorney general Maria Consuelo Porras has also been sanctioned by the United States “due to her involvement in significant corruption”.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said “During her tenure, Porras repeatedly obstructed and undermined anti-corruption investigations in Guatemala to protect her political allies and gain undue political favor.”

It is in this context that Arvelo’s party, Semilla, emerged amidst massive countrywide protests in 2015 that ousted then-president Otto Peréz Molina for their involvement in serious corruption.

It is one of the few political parties that has maintained a strong track record in support of strengthening democracy and the rule of law, and Arevalo has run an anti-corruption campaign that seems to have resonated among voters.

Torres in public comments on Friday stated, without proof, that supporters of Arevalo “want to steal the election”, perhaps setting the scene for fraud accusations in the case of her loss.

Endemic corruption and electoral irregularities may be the topic du jour among analysts, but what’s at stake goes well beyond the headlines— authoritarianism is also on the ballot.

Guatemala has been battered by crime in recent years, a phenomenon worsened by bad governance and informal alliances with criminal structures. Even further worsening that trend, nearly 60 percent of the population lives in poverty, according to government statistics.

Inspired by neighboring policies in El Salvador, Torres has promised brutal crackdowns on crime.

“Even if it hurts, I am going to adopt the Bukele model,” Torres said in a televised debate on June 20. A massive expansion of governmental power under the populist guise of being tough on crime would be devastating for civil society in Guatemala.

The country has weak institutional democratic structures and is already struggling under the weight of traditional parties who have built sophisticated political machinery. They have also flooded the judiciary with sympathetic appointments and intimidated magistrates who oppose them.

Journalists, investigators, and opposition politicians alike have fled the country after persecution by powerful elites and politicians in recent years.

A victory by Torres would contribute to rising autocracy in the region and allow her party to even further cement power via new populist “anti-crime” powers that would in reality be empowering it politically.

The Biden administration has been slow to criticize the synthesis of crime and politics in Guatemala. Instead, it has sought partnership for its migration “deterrence” policies in the country, which lies on the largest migration corridor in the Americas, at any cost.

International attention on attempts by corrupt officials in Guatemala to undermine elections seems to have changed that for the moment, but as attention fades after elections the U.S. may go back to quietly ignoring autocratic tendencies in return for cooperation on migration policies meant to reduce numbers at the U.S. southern border.

A victory by Arvelo may well result in attempts by establishment political parties to remove him via strategies both legal and not and would test the mechanisms meant to protect elections.

Even if he survives such attempts, he will have to rule without a majority in the legislative branch and be surrounded by powerful elites who would likely try to undermine his agenda.

Guatemala has a rough prognosis for its immediate future however the election shakes out. But for the sake of the Guatemalan people, who deserve to have their voices heard, we at PWS hope the process goes as smoothly as can be expected.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Ecuador also goes to the polls Sunday. When current president Lasso dissolved the government in May he set the stage for new legislative and presidential elections in the country.

The campaign has been plagued with violence. At least three candidates have been killed amidst a crime wave as organized crime groups try to impose their will on the process, including presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio, who was gunned down in the capital, Quito.

The presidential race is expected to go to a runoff second round.

Spanish Word of the Week

Por si las moscas - “just in case”

The literal translation of Por si las moscas would be “for if there are flies”, but the phrase is used to describe preparation for an event that may or may not occur.

No olvides el paraguas. Por si las moscas- “Dont forget your umbrella, just in case.”

We’d love to know more about the origin of this phrase. Do you know where it comes from? Drop a comment illuminating us.