Dollarization and the Venezuelan supermarket myth

Alternative media pundits often film themselves in Caracas supermarkets, supposedly proving reports of food shortages are a myth. But there’s one group they haven’t managed to convince: Venezuelans

Caracas, Venezuela – In November 2021, the journalist Denis Rogatyuk uploaded a video of himself visiting a Caracas supermarket. As he walks, he talks, vlog-style, about Venezuela’s economic situation.

“Sugar, meats, anything you can possibly imagine, you can find in shopping centers like this, all around Caracas and Venezuela, so don’t believe everything you see on mainstream TV,” he says, before signing off.

Rogatyuk’s video is just the latest in a series of uploads by various indie journalists and content creators, purportedly showing that Western media reports of chronic shortages of food, personal hygiene supplies and other basic goods are little more than Yankee propaganda. Max Blumenthal of The Grayzone posted a similar video in 2018, garnering over 320,000 views. The intimate, grassroots activity production style is seductive - but are they right?

Venezuela has been facing a critical economic, political and humanitarian crisis that has driven some six million people to leave the country, leaving the country with a declining population of 28 million. The situation reflects a complex web of problems with debt, the 2014 oil price crash, over-reliance on imports, and US sanctions whose effects hit ordinary people hard.

But its role as a geopolitical faultline stems from political differences between the government and the US: in 1999, the country elected radical leftist Hugo Chávez, whose socialist agenda and inflammatory rhetoric needled Washington.

The governments of Obama and then Trump slapped increasingly broad sanctions on Venezuela in 2014 and 2017, ostensibly to pressure Maduro over human rights violations during waves of protest, but the measures are widely regarded as politically motivated. This has prompted elements of the radical left to dismiss Venezuela’s problems as a mixture of Western propaganda and a direct result of US sanctions. Venezuela's economic collapse began before sanctions on the country existed, although they accelerated its decline.

When Rogatyuk reaches the coffee section, he explains that the price is displayed in Bolívares Soberanos, and a bag of coffee is going for around 40 cents. But the price label actually reads REF1.76, with no reference to the local currency at all.

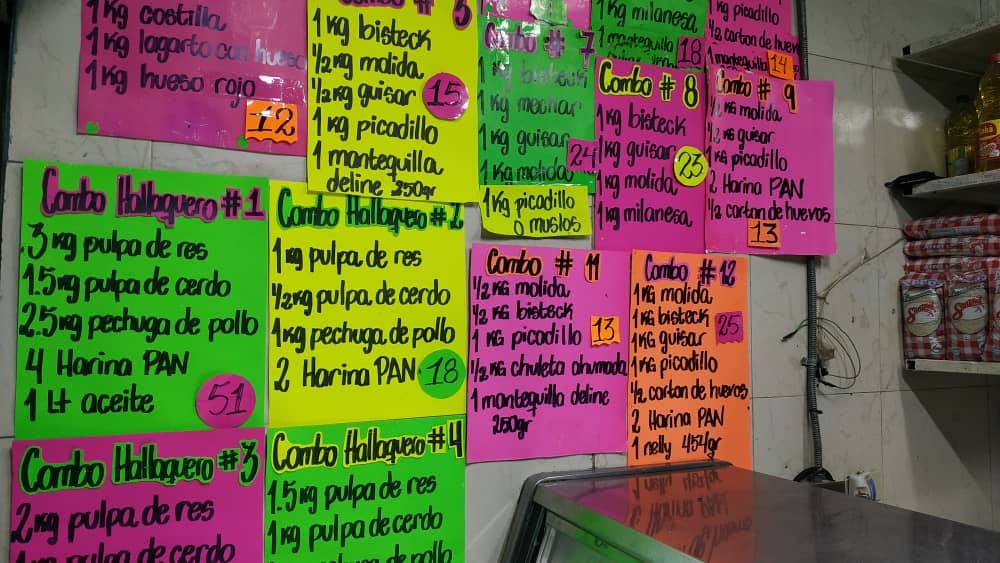

Venezuelan businesses use a system of abbreviations or “references”, usually REF or similar, to indicate to buyers that the price is a reference to the current dollar value. They could just use the dollar sign, but they would risk being fined or temporarily shut down for speculation, distortion of the economy and rejecting the official currency by consumer rights watchdog, INDEPABIS.

By early 2021, the average monthly salary of a private sector worker in Venezuela was around $70, according to a study by the Venezuelan Finance Observatory. In the public sector, where wages are not indexed to the dollar, the average salary was USD4.70 per month, although bonuses such as food vouchers and rewards for good performance, along with fixed State payments, allow public sector workers to feed themselves. The monthly minimum wage in the public sector was around $2.14 by this week’s exchange rates.

In Venezuela, it’s now common to find US dollars openly circulating. It has become the de facto currency for many goods, allowing vendors to set prices without having to constantly adjust them in reflection of the hyperinflation of the Bolivar. President Nicolás Maduro has devalued the currency twice: in October 2021, before Rogatyuk posted his video, the Bolívar Soberano had been devalued by removing six zeros and the new currency was called the Bolívar Digital.

Hyperinflation has been so high that a million dollars’ worth of Bolívares Fuertes in 2012 would have been worth just three dollars in 2018 and probably just a few cents today, although an exact calculation is difficult because official statistics have become more opaque.

But despite the government’s attempts to stop this informal dollarization, the phenomenon has only become more marked, even in areas where support for Maduro and chavismo is high.

To gain control of the situation, the government has decided to shift from banning the use of dollars and embrace de facto dollarization during 2021, balancing the Central Bank’s official exchange rate with the parallel dollar. Businesses which display their prices in dollars have to display the exchange rate they’re using each day, allowing them to charge clients in Bolívares or the dollar equivalent.

Another popular myth about Venezuela’s food supply is that the needy can get all their food through Local Supply and Production Committees (CLAP, by their Spanish initials), a state food programme which guarantees a package of food and, in some cases, hygiene products to everyone in the programme.

Like so many state programmes here, it got off to a good start. But as time went on, the quality and nutritional value of the products deteriorated to the point where they failed to comply with the standards of Venezuela’s National Nutrition Institute.

Moreover, the goods aren’t guaranteed to arrive on time: in some cases, communities have been left waiting months. This problem means that some Venezuelans have lost weight and muscle mass, with some people who depend primarily on the program reporting losing as much as 11kg’s in 2019.

Media such as The Grayzone claim that sanctions imposed by the US are having a catastrophic impact on the programme and there’s an element of truth to this. US sanctions apply to top government officials and companies associated with them, such as the state oil company PDVSA, leaving the country’s crumbling economy even more isolated than it was before. Despite claiming that the cash crunch has forced to reduce funding for the CLAP program however, the Venezuelan government continues to publicly announce purchases of new military equipment and host lavish public ceremonies in Mira Flores.

With the new flow of dollars, the part of the population that has access to that currency is enjoying a small taste of normality. Despite the sanctions and pandemic there are surprising signs of revival and economic prosperity. Ferrari outlets are opening and PlayStation 5s and high-end computers are appearing on the shelves.

The same dynamic applies to food in the supermarkets. It is more common to find imported items than goods produced in Venezuela, such as Quaker brand cereal, Heinz ketchup, and US brand toilet paper. This phenomenon has given rise to businesses specialized in imports called Bodegones, who stock principally North American products, but the prices, almost three times higher than in neighboring Colombia, are out of the reach of many.

Outside of Caracas, the situation is very different. The rest of the country still suffers from shortages of gasoline, and food prices are erratic. Many areas don't have gas for cooking, and potable water seems like a throwback to a past long vanished.

The situation in Caracas is not as rosy as sympathetic media suggest. Rather, the ever changing reality is too complicated for even Venezuelans who live here to understand. The country’s economic evolution is chaotic and unpredictable, and it is impossible to predict what the government will do next.

People have doubts that even the modest progress of recent months will last, but even so, those in Caracas are clinging to what normality they can for the first time in a long while.

Stories we’re watching:

The phones of thirty-five journalists and human rights activists in EL SALVADOR were hacked by sophisticated software. Twenty-two of the phones were associated with the newspaper El Faro, which has been investigating a scandal involving government negotiations with gangs. The researchers who discovered the attack could not say for certain who was responsible but thought the government ‘very likely.

A car bomb in Saravena, Arauca in COLOMBIA, where fighting between ex-FARC dissidents and ELN has killed at least 37 and displaced over 1000 in the Venezuelan border regions, detonated in front of the headquarters of a local social organization, killing one and wounding 5. It is not immediately clear who was responsible, but the Pastoral Social in Saravena this morning told PWS that "this represents a serious escalation. It means that civilians have become direct targets in the conflict rather than collateral ones"

Argentina has experienced a heatwave so intense that it was, for one day, the hottest place on the planet, with temperatures reaching 45°C (113°F). The brutal temperatures have triggered mass power cuts as demand for power for air conditioning overloads the grid. The situation is raising tough questions about global heating in the national debate.

Spanish Words of the Week:

Anaquel: a ledge, bracket, or supermarket shelf. Not to be confused with aniquilar, which means to annihilate, possibly with a shelf

Arrecho: In much of the Spanish speaking world, this means one is *ahem* ready for some action, but in Venezuela it can mean a wide range of things starting with “I am extremely angry” to “this fucking sucks”. The not-so-subtle difference between the two uses can lead to some hysterical misunderstandings in neighboring countries.