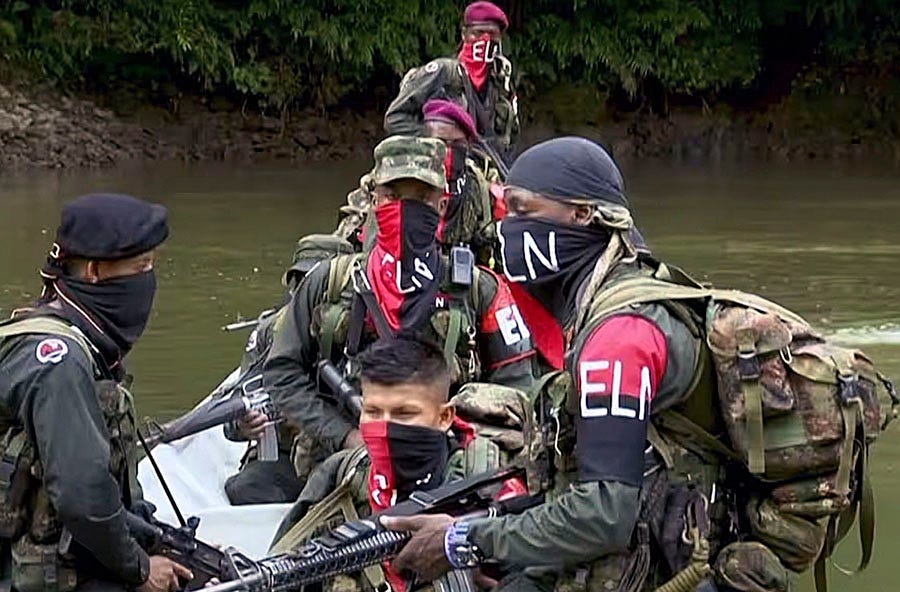

ELN consolidates control in the Venezuelan-Colombian borderlands

A regional offensive against other leftist rebel groups has displaced more than 60,000 people and left ELN as the hegemonic power in the region

April 25 marked one hundred days since Colombia’s largest remaining rebel group, the National Liberation Army (ELN) launched a major offensive in the Venezuelan/Colombian borderlands to solidify control over Catatumbo, in the east of the country. The regional attacks, which took place on January 16 of this year, generated the biggest humanitarian crisis in the country in 10 years.

The most recent bulletin from the Defensoria reports 64,397 people displaced, and 104 killed by fighting in the region between the ELN and FARC-dissident group Frente 33. In the same report, authorities state that the number of deaths is likely dramatically under-reported as most of the fighting occurred in areas where the State maintains little or no presence.

President Gustavo Petro declared “an interior state of commotion” that granted broad powers to the military in the region, as well as temporarily expanded presidential powers in Catatumbo in January. By law, the decree can last a maximum of 90 days and was lifted on April 24, but the fighting is far from over.

On January 16, ELN fighters arrived at workplaces and homes asking by name for men associated with Frente 33 and killing those they found. Simultaneously, battalions that included ELN fighters from other departments in the country surrounded the towns of Teorama, Convención, Hacarí, Tibú, and El Tarra, cutting them off from the rest of the country.

Once isolated, they began searching for targets from Frente 33 within the communities, killing some and kidnapping or disappearing others. According to a March 25 report from Human Rights Watch, dozens of family members of victims still have no idea what happened to their loved ones.

Frente 33 is a FARC splinter group that forms part of the “Estado Mayor de los Bloques y el Frente”, which is involved in ongoing peace negotiations with the Colombian government. In recent years they have expanded their presence in Catatumbo. Until November 2024, they had an informal non-aggression pact with ELN in the region. As part of that agreement, they had agreed not to expand into illicit businesses controlled by the ELN.

Catatumbo is a strategic zone for armed groups due to both its coca production — the second-largest coca-producing region in the country — as well as its location on the Venezuelan border, which makes it a valuable smuggling route for both cocaine and illegally mined materials like gold.

The region has also seen a slow but steady increase in poppy production in recent years, the raw ingredient in opioids — though coca remains, by far, the most common illicit crop in the region.

The coordinated attacks were meticulously planned, according to PARES, a human rights watchdog group that conducts investigations in the region, and part of a larger strategy to consolidate power in the borderlands. Though Frente 33 has not been eradicated in Catatumbo, the ongoing fighting has been a strategic victory for ELN.

Military forces during the State of Commotion focused on evacuations in affected communities, as well as constructing defensive positions near Cucuta, the capital city of Norte de Santander, where Catatumbo is located.

These security measures, however, did not prevent a series of bomb attacks on military structures and police precincts near the city. The ELN as a general rule does not seek open confrontation with security forces as FARC rebels did during the country’s 53-year civil war. Instead, they retreat from large military deployments, fading into the dense jungle hills of the region, or blending into civil society, and return to carry out asymmetrical attacks like bombings of infrastructure or ambushes of small patrols.

The tactics mean that deployment by the Colombian military into ELN-controlled zones is both ineffective from a strategic perspective and extremely dangerous for deployed personnel.

Fighting between the ELN and Frente 33, however, is ongoing, and both groups release videos of ambushes and counter-ambushes that include the use of bombings carried out by drones, anti-personnel mines, and small arms fighting.

Frente 33 has been effectively paralyzed in the region, unable to continue the activities that fund their actions, such as coca cultivation, extortions on civilian populations described as a “war tax”, and cross-border smuggling, for fear of becoming targets for coordinated ELN attacks.

Further complicating the dynamic, the ELN also operates in large sections of Western Venezuela, especially in the states of Zulia, Táchira, Apure, and Amazonas. They often use the border to escape confrontations with security forces on either side, fleeing to one side or the other to escape large deployments.

Some NGOs in the region claim that low-level members of Venezuela’s National Guard actively collaborate with ELN brigades in the region, selling them weapons or turning a blind eye to their presence in return for bribes. The aid is likely based on corruption rather than top-down support from the Maduro government. Military officials in Colombia have also been caught selling the ELN weapons.

The ELN has completely abandoned “Total Peace” negotiations with the Petro government, which has just a year remaining in office. It is consolidating control in the regions where it maintains a presence and seeking to impose a monopoly on non-state armed activity in the Venezuelan/Colombian borderlands.

This latest offensive against other leftist rebel groups in the regions is merely the latest in a years-long effort to oust FARC dissidents from the border, not just in Catatumbo but further south in Arauca as well.

Military offensives by the Colombian government, carried out across decades and half a dozen administrations, have failed to dislodge the group, or even considerably weaken it.

Some analysts here are now calling for an aggressive military campaign against ELN forces across the country. Their frustration is understandable, and negotiations with the group have clearly failed. Returning to the failed military strategies of decades past, however, is unlikely to yield a different outcome than dozens of previous attempts.

The oldest rebel group in the country have become masters of asymmetrical conflict strategies and has survived 60 years of warfare with the Colombian state. Most experts who study conflict in Colombia recommend a combination of military strategy and state-building in areas of ELN control.

Currently, however, it is the armed groups who are the hegemonic power in Catatumbo, not the Colombian military, and certainly not civil society.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

Most of the headlines in newspapers in LATAM this week have been focused on the death of the pope. Boy, do they love the pope here. LOTS of pope stories. But we managed to address a few other issues as part of our new LATAM Daily Wires vertical. Have you signed up for that yet? You should.

The ex-Foreign Minister in Colombia this week accused President Gustavo Petro of drug addiction in an open letter published to social media. The resulting controversy set off a political firestorm, even among erstwhile Petro allies, and shows increasing cracks in his own cabinet.

Venezuelan opposition leaders have been increasingly supporting regional attacks against their own diaspora. María Corina Machado has particularly adopted Trump rhetoric towards Venezuelan migrants, claiming they “destabilize” the Americas. She has also been falsely claiming that the Tren de Aragua is an international terrorist group led by Nicolas Maduro, bent on undermining the U.S.

The trend seems to illustrate that close ties with Washington are more important to her than the people she claims to represent.

The Trump administration drew criticism in Mexico this week after running a series of threatening ads towards migrants that Mexican officials said could “incite violence against vulnerable communities.”

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum asked television channels to remove the ads and proposed a bill to Congress that would make stigmatizing migrants on Mexican television illegal.

Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele proposed a prisoner swap with Venezuela that would entail the release of the more than 200 Venezuelans currently held at the terrorism detention center CECOT. In exchange, he released a list of names of political prisoners held by Venezuela. The message, posted to X, also contained a number of false claims, most notably that El Salvador does not hold political prisoners.

What We’re Writing

We have been *so* busy writing the new vertical this week, but that hasn’t stopped us from doing some field work as well. Joshua has been hanging out with ex-soldiers who were convicted in Colombia’s infamous “false positives” cases, and who now do peace work in Medellin for an upcoming article at the The New Humanitarian.

Daniela is heading back to Colombia from Mexico for a couple of months while she works out visa stuff. Her photo from last weeks PWS feature on the Zapatistas was selected by NACLA to be the “Latin American journalism photo of the week”! Pretty cool stuff. We always forget some of the editors we work with are also subscribers to the newsletter.

Hola jefes!

Spanish Word of the Week

"Echando la hueva" (Mexico)

Literally translated as “tossing the egg”, echando la hueva is an expression that can be used to say you are being extra lazy at the moment.

Eggs are also used in a number of other Latin American Spanish slang words and expressions, particularly in Chile where ahuevonado is used to describe someone stupid, the verb huevear means “to mess around” and the phrase “agarrar para el hueveo” means to tease someone. Other variants are decidedly more offensive in polite company, such as huevón, meaning “idiot”, a term also used amongst close friends as a lighthearted insult. In Mexico me da hueva, literally meaning “give me egg”, is a slang phrase for “I don’t want to” or “the very thought is making me tired”.

If this talk of eggs has gotten you a bit confused, then feel free to say “¿Y que huevada?” This is another egg derivative and means “What the hell is going on?!”

Or in Colombia you can just call your friend güevón (perhaps best loosely translated as ‘dumbass’) and move on with your day.

Hasta pronto, piratas!