Migrants brave dangerous jungle and armed groups to journey from Colombia to the US

Covid recessions and insecurity are prompting Caribbean and West African migrants to attempt the crossing - but between armed groups, disease and treacherous terrain, many never make it

Necocli, Colombia- Colombia has officially reopened its land border with Panama after a year and a half of pandemic closures. The news has prompted thousands of mainly Caribbean and West African migrants to trek to the frontier.

For many, their trans-continental journey officially begins at the Darien Gap: the treacherous, tightly packed jungle between Panama and Colombia which the builders of the Pan-American Highway were infamously unable to penetrate. The trail has served as a smuggling corridor for goods, people and narcotics for decades - and is controlled by armed groups with roots in Colombia's civil war.

Migrants take a boat from the tourist town of Necoclí across the Caribbean gulf to the hamlet of Acandí, before continuing to the Las Tecas staging camp at the trail’s entrance. The jungle settlement is bustling, crowded with vendors selling overpriced goods and blasting tropical dance music. Migrants mull about, nervous about the trip ahead, checking their gear and gathering in the small groups they travel with. Here, they hire informal guides for the five-day jungle trek, who will wake everyone up at 3:45a.m. the next day for a 5 a.m. departure.

Within 10 minutes, they are crossing waist-deep rivers, soaking their clothes and footwear. Walking upstream is slow, the uneven stones taking a toll on the travellers' ankles. Many are hiking through the tropical jungle in flip flops, crocs, or now-ruined Nikes. One migrant steps into shin-deep mud before pulling their foot out only to find it barefoot — their shoes buried. Some recover their shoes. Others continue in their socks.

A woman faints after just a few hours. She is in no physical condition for this trip, but she has no choice: the alternative is staying in Colombia without her family. Her fellow travellers help her up, but a few hours later she is reduced to crawling on her hands and knees through the mud. The people urging her to continue seem wildly irresponsible, or totally unaware of how much farther they have to go.

The journey will take them deep into territory controlled by the most powerful Colombian narco paramilitary group in the country, the Clan de Golfo, also known as the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC by their Spanish initials).

As of late September, over 15,000 migrants awaited transport across the small gulf, where they will begin a journey of over 4,000 kilometres to the US border. The migrants are mostly Haitian, but also include Cubans, Venezuelans, and West Africans.

Of the direct arrivals from Haiti, most that spoke to Pirate Wire Services said they were migrating because of insecurity rather than economic reasons. Haiti has seen a massive rise in gang violence and political instability in recent years, culminating in the assasination of their president in July.

Many do not have the necessary documents to apply for visas in Mexico, and choose to start further south in hopes that overwhelmed border officials will be more forgiving to migrant caravans crossing by land, a hope borne out in practice in recent months throughout Central America.

However, the majority have been working in other South American countries, such as Chile, Brazil, Peru and Ecuador— countries hard hit by covid-induced recessions, and regions that have also recently experienced an explosion in anti-immigrant sentiment.

“What are you going to write?,” Dearson, a Haitian migrant who declined to give his last name, asked Pirate Wire Services on the beach in Necoclí, accusingly. “Will it be more lies? Will you say we are violent? That we bring disease? Will you dehumanize us like all of the other journalists do?”

Dearson had worked under the table in Chile for almost two years, but was unable to obtain residence. The pandemic prompted a spike in xenophobia and racism in both the media and the population at large. Now, he is headed to the United States- Las Vegas -where a cousin has promised to help him claim asylum and find work.

Migrants will be escorted through the jungle territory of AGC by informal guides before crossing into the Panamanian jungle. This is controlled by a patchwork of criminal groups and smugglers who have committed grave violence against many of those making the trip, according to Doctors Without Borders, which maintains a post on the Panamanian side. Afterwards the journey hardly gets easier, with five more borders and 4000 more kilometers to cross to reach the Rio Grande.

“I don’t know, I hear [criminals] are robbing people of everything they have,” said Yordany Herrera, a Cuban who had travelled by land from Peru, where he had been living since last March. “I’m not worried though. I will stop to work along the way if I need to. I’ve been a chef, a construction worker, a waiter, a carpenter. I can do anything.”

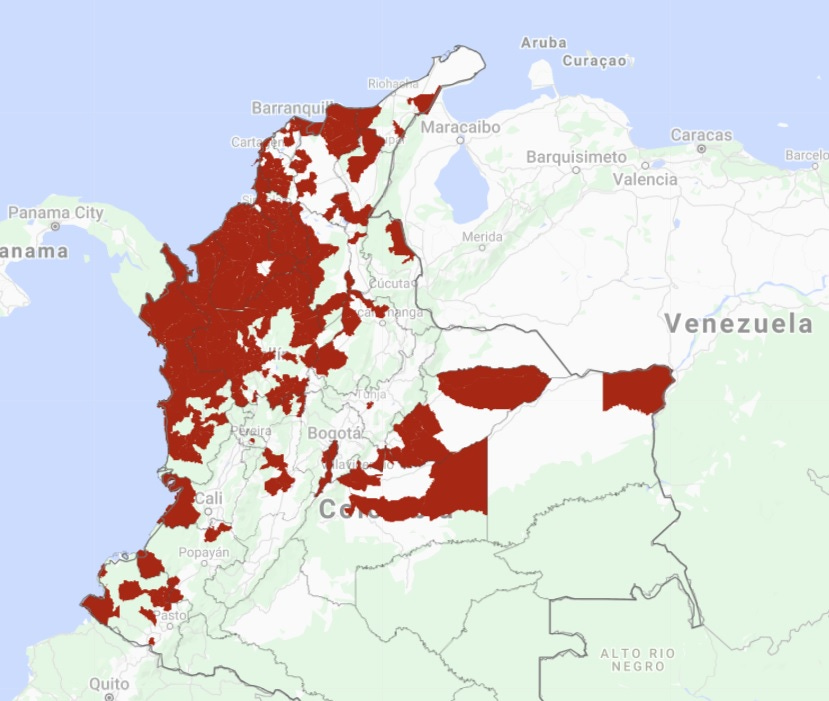

The Clan de Golfo controls this region of Colombia completely, using it as a shipping hub for cocaine and smuggling as well as a staging area for their ongoing conflict with the armed leftist criminal group, the National Liberation Army (ELN) in the nearby departments of Chocó and Antioquia. The shadow war there has led to thousands of displacements as civilians flee the fighting.

AGC is descended from paramilitary “self-defense” forces that fought on the side of the government during Colombia’s 50-year civil war, which, at least officially, ended in 2016 with the signing of a historic peace deal. The forces committed grave human rights violations during the conflict, including participation in Colombia’s “false positives” scandal, in which the government killed over 6,000 farmers and claimed they were rebel fighters to inflate casualty reports.

According to the US State Department, AGC is now the most powerful criminal group in Colombia, and controls the largest amount of cocaine smuggling. The United Nations considers them a terrorist organization.

Panamanian officials have recovered 50 bodies so far this year in the Darien Gap, more than double 2020, but they believe that is only a small portion of those who have died making the trek, as most deaths go unreported and the remains are never recovered. More than 90,000 Haitians have been processed so far this year by the country’s immigration officials.

Dearson, however, is undeterred. He switched fluently between Spanish and Haitian Creole as he chatted with Pirate Wire Services from the beach encampment in Necolí. “I don’t understand why all of these countries, including the US, want us to suffer. All we are looking for is work and a chance to come out ahead.”

When asked if he spoke English, Dearson smiled and replied “Not yet, but I will. I learned Spanish in less than two years. I can do anything I set my mind to.”

Reporting for this story provided by Jordan Stern, from the Darien Gap, and from Joshua Collins, from Necoclí