The Mapuche People have been in conflict with the Chilean State for decades. Why?

Four key points to understanding Mapuche resistance, and how Boric became mired in a conflict he inherited

Hola Piratas!

It’s been a fruitful week of marauding for the PWS team. Amy is off charting the Chaco, an indigenous region in the Argentinean/Bolivian/Paraguayan borderlands on assignment for the New Humanitarian and Daniela is in Popayán, Colombia, a conflict region in southwestern Colombia known for coca production for a story at El Pais. That means Paulo and Joshua are all hands on deck for this week's newsletter as our intrepid jefas strike off into the unknown.

As part of our piratical labors, this week's story is an explainer on ongoing conflict between the Chilean military and indigenous communities in Southern Chile. Land struggles between the Mapuche people and giant corporations are ongoing, but what started this decades-long conflict over land rights, and how has the situation damaged the new presidents standing with his allies? We explain all that and more.

All this piracy doesn’t pay for itself however. If you like what you read, don’t forget to consider a paid subscription to PWS, which starts at just $5/month.

The Mapuche People have been in conflict with the Chilean State for decades. Why?

From an overwhelming electoral victory in December 2021 to a government that, four months after taking office, is faltering politically and socially, the recently elected progressive president Gabriel Boric in Chile has faced a dramatic fall from grace.

The reason for plummeting approval ratings? Analysts point to rising inflation, linked to world food and fuel prices, as well as after-effects of the pandemic, and some political errors, such as failing to get their merger in Congress to approve the proposal on the use of private pension funds. A third factor is the increase in insecurity, especially in the south of the country, an area of conflict between the Chilean State and the Mapuche people.

At Pirate Wire Services, we decided that it was a good time to delve a little into this last problem, which has an important historical significance in Chile, and presents important context on the ongoing process of ratifying a new Constitution.

Who are the Mapuche people?

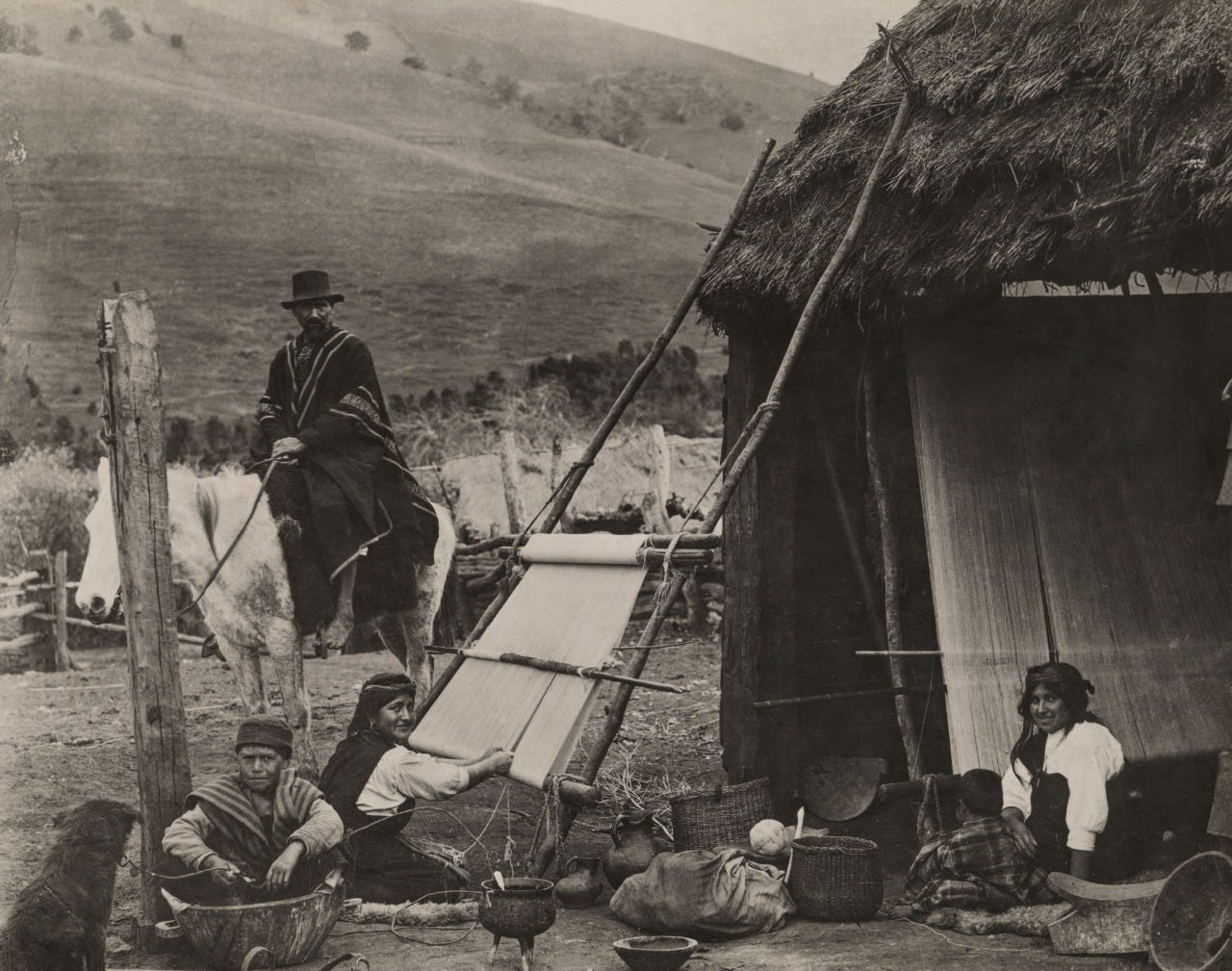

They are an indigenous ethnic group that has historically occupied territories in southern South America. Their territory, whose ancestral name is Wallmapu, includes regions of Chile and Argentina. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Mapuche people resisted European advances into their territories and, according to historical sources, managed to later forge diplomatic relationships with them, implementing both economic and political agreements.

However, once the Spaniards had been expelled and the Republic of Chile had been created through independence, it was the Chilean State that, in the mid-nineteenth century, invaded its territories by means of arms and annexed it, subjugating it to its institutions.

This conquest created a centuries long resistance movement among the Mapuche people, who are the largest indigenous ethnic group in Chile, with nearly 2 million members. That resistance has extended to today, although with evolutions in the political and economic objectives.

What is the current state of the conflict between the Chilean State and the Mapuche?

In the last decade, large forestry and agricultural companies have settled in the regions of La Araucanía and Bío-Bío, where the presence of indigenous Mapuches is concentrated. They have denounced that the logging and livestock industries pollute and destroy their homelands, actions they describe as “ecocide” that marginalize their communities.

Mapuche resistance has manifested itself in two ways: politically, via institutional process and via armed resistance. In the first case, Mapuche werkenes (or spokespersons) have chosen to participate in social movements and political parties in order to effect an improvement in the situation between their community and the State. An example of this strategy is Elisa Loncón, the Mapuche academic who presided over the Convention that drafted the new Constitution.

There are also Mapuche groups that have chosen to fight for the autonomy of their territory by resorting to violent acts, such as attacks on factories and transport companies in the area, roadblocks and even clashes with state forces. The striggles have resulted in dead Mapuche as well as civilians, police and military. The best known of these groups is the Arauco Mallejo Coordinator (CAM by their Spanish initials), who espouse armed resistance and define themselves as independent from the Chilean state. They affirm that their actions are a necessary measure against structural violence committed by the state as well as private companies.

What has been the historical response of governments, including Boric's?

From the Chilean side the response has been the use of force by both the Carabineros —the Chilean police force— as well as the army. The UN in 2020 demanded that violence against the Mapuche people in the region of La Araucanía be investigated, accusing the Chilean state of human rights violations.

Ignoring UN recommendations in 2021, right-wing Sebastián Piñera, then Chilean president, declared a State of Emergency in the Mapuche territories and targeted the CAM for carrying out, what he called terrorist actions. This act, which clearly violated the fundamental rights of the citizens of that area, was repudiated by the Chilean left, which at that time was led by Boric and members of his current administration. Those criticisms returned to haunt the 36-year-old president in May, when he also announced similar measures in that same territory which are still ongoing.

However, in the case of Boric, the State of Emergency is limited to transportation corridors. Under the current terms of engagement, military in the area are only able to intervene against violent acts that occur on the roads, not off them. Despite that nuance, Boric’s decision earned him harsh criticism from political allies closely aligned to his government.

Meanwhile, decades of ongoing violence has resulted in La Araucanía becoming the poorest region in the country. Advocates of the strategy of Chilean public forces say this is a result of a drop in foreign investment due to the deteriorating security situation. Whether true or not, the significant increase in poverty occurred alongside the appearance of new criminal gangs in a region with little to no state presence.

To resolve the conflict, Boric has promised to establish dialogue committees, create a Ministry of Indigenous Peoples and deliver more resources to the area. This strategy has been rejected by the majority of Mapuche groups, who have lost any faith in the progressive president.

Could the new Constitution in Chile present a solution to the conflict?

The current Chilean Constitution does not recognize the Mapuche people. Chile’s new proposed Magna Carta was drawn up in a convention presided over by a Mapuche academic and that included representatives of 10 other indigenous communities.

The new proposed Constitution represents a huge step forward for indigenous in the country, recognizing Chile as “a multinational and multicultural state”. It also “recognizes and guarantees, in accordance with the Constitution, the right of indigenous peoples and nations to their lands, territories, and resources,” as per article 79 of the text.

In addition, the State must establish "effective legal instruments for regularization, demarcation, titling, repair and restitution" of indigenous lands. For Adolfo Millabur, who was on the Constitutional Committee, this would create "a transitory body that registers and identifies” areas of land-dispute between indigenous peoples and the private sector.

The proposal also recognizes the legal systems of indigenous peoples and specifies that, where they function, they must respect the Constitution and international treaties, and that any challenge to their decisions will be resolved by the Supreme Court.

That there are indigenous groups that view these changes with pessimism. Among them, the CAM recently stated that the plurinationality proposed in the new Constitution is an "empty aspiration" and called for continued "frontal resistance."

"In these times of strategic confusion, while Chile boasts of being a country supposedly on the way to plurinationality, we call for unity and coherence in the frontal resistance against capitalism and colonial persistence in the Wallmapu", they expressed in a statement.

It would seem that even if the Constitution is approved, which is far from certain, it is unlikely to resolve a conflict which has been ongoing for decades.

Top Stories in Latin America

Migration numbers in the America’s rose dramatically in June, especially through the infamously deadly jungle crossing between Colombia and Panama known as the Darien Gap. New visa restrictions in Central America and Mexico have forced those who would migrate to the US and Mexico to start their journey further south, and deaths are rising as a result.

Migrants on the trail face not only the natural dangers of a mountainous jungle trek across inhospitable terrain, but also the potential of being preyed upon by criminal groups. Images of migrants abandoned by their traveling companions after suffering injuries went viral on social media this week. To learn more about the Darien Gap you can read this piece by Joshua for The New Humanitarian, after he and photographer Jordan Stern made the journey.

Feminist networks in Mexico have been helping women in the US secure acess to abortion procedures after the Supreme Court’s decision last month overturning Roe v. Wade and opening the door to restrictive abortion laws in states around the country, including Arizona and Texas.

Abortion was decriminalized in Mexico last year, and Women’s Rights movements in Sonorra are helping their northern neighbors obtain appointments, organize transportation and providing guidance to their gringa counterparts.

Increasing violence and insecurity in Haiti is likely to result in food shortages, the United Nations reported this week. The World Food Programme says worsening crime as well as gang violence is making it difficult to transport much-needed foodstuff and other aid.

In the capital of Port-au-Prince, gangs have blocked roads and seized control of entire neighborhoods, restricting access of humanitarian workers. More than one million people in the capital are already food insecure, according to the WFP, and depend on humanitarian aid groups for survival.

What we’re writing

Amy covered new legislation in Argentina for HIV patients for the Lancet. The law also makes provisions for patients with viral hepatitis, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections.

Daniela covered a rise in crossings through the Darien Gap by unaccompanied minors for El Pais. “Minors who migrate alone: a tragedy that grows in the Colombian borderlands”. The transit of unaccompanied or separated migrant children and adolescents increased in 2021 not just due to visa restrictions, but also due to the resurgence of humanitarian crisis’ in the region

Spanish word of the week:

Coypu are small capybaras who live in arid regions of South America’s southern cone. Amy has adopted dozens so far as a critical part of her field work. Joshua is demanding they be delivered to his apartment in Bogotá

Very good article Paulo. Parallels can be drawn between the situation of the Mapuche and the struggle of the Palestinian people for statehood. I also laughed at the piece at the end about the Coypu. Did you know that there are also Coypu in the Norfolk Broads, a Lakeland area in the East of England? They were originally brought in to (I think) keep the population of mink under control. But things got out of hand and the Coypu population itself exploded. There are now "Coypu Patrol" trucks to be seen in the Broads area. At first I thought it was a joke, but it's deadly serious as the Coypu are killing off a lot of indigenous species. Keep up the good work! John Booth (Amy's dad).