The Rubio and Trump story over Venezuelan boat bombing is full of holes — and fabrications

The Tren de Aragua doesn't traffic drugs internationally. Is this an escalation in drug policy or simply importing the 'War on Terror' to the Americas?

US actions in the Caribbean Sea last week transformed from performative to lethal, when a drone attack on a speedboat near Venezuelan waters killed 11 people, according to government statements.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio and US President Donald Trump both claimed that the boat was carrying drugs and belonged to the Tren de Aragua in public statements shortly after the attack.

But as someone who has covered these topics extensively, a number of US claims about what happened strike me as extremely dubious. Some of their other claims are much simpler to describe: they’re lies.

The deadly attack occurred just days after US ships had begun circling Venezuelan waters, and rhetoric from Washington DC had grown more aggressive. US officials did not provide proof for their accusation or any details about those who were killed.

Rubio initially said the vessel was bound for Trinidad and Tobago, but Trump immediately contradicted him, claiming it was headed for the US. The next day, Rubio reversed course in live statements, saying the craft “was eventually headed for the United States.”

In the absence of concrete information, speculation grew among experts and Venezuelans alike. If the vessel was a small fastboat with limited cargo capacity, why would there be so many people aboard? Wouldn’t smugglers want to carry merchandise rather than extra people? Was it one of the many migrant boats that commonly run between Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago? But if that were the case, wouldn’t the same principles apply as a drug boat? Wouldn’t the crew want as many migrants as possible to maximize profits, just as smugglers would want to maximize cocaine payload?

Was it a fishing boat? We may very well never have satisfactory answers to those questions. But the number of people on board isn’t the only part of the story that raises eyebrows.

Even the DEA says the Tren de Aragua doesn’t traffic cocaine

The Tren de Aragua is not an international drug trafficking organization in any meaningful sense, and certainly lacks the logistical capabilities and sales contacts to transport drugs 3,200 km (roughly 2000 miles) to US shores, and sell, presumably, tons of cocaine.

Since the State Department declared the Tren de Aragua a terrorist organization in March, the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) has been required to report on its activities.

According to the most recent DEA report, Tren de Aragua drug activity “occurs mainly at the street level and involves the distribution and sale of tusi in specific regional markets.”

In the same report, the DEA states that based on testing, 84 percent of cocaine seized within US borders is produced in Colombia.

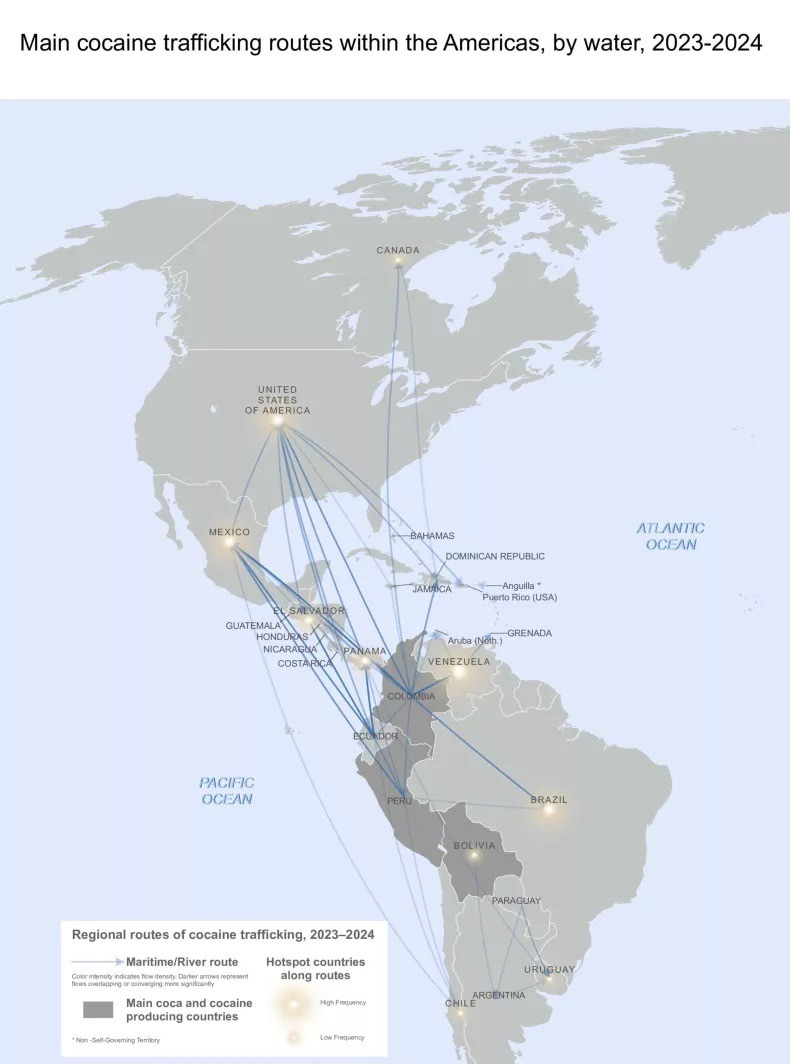

Venezuela is not a cocaine producing country, and though smuggling does occur through the country, Pacific routes from Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador account for 87% of cocaine trafficking to the United States, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

That is to say, if the principal goal of the Navy blockade is to disrupt cocaine trafficking to the US, they are deployed near the wrong countries, and in many ways, the wrong ocean entirely.

The Trump administration has also claimed that Maduro controls the Venezuelan gang, and uses them to “invade” the United States — the highly questionable justification for the use of the Alien Enemies Act to declare Tren de Aragua members “terrorists”.

This is completely untrue. Academics who study the Tren, as well as reputable international journalists who cover the crime beat in Latin America, have thoroughly refuted the idea that the Venezuelan government controls the gang.

U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies have also refuted this claim. A classified assessment by the National Intelligence Council released in April repeatedly stated that there was no evidence of coordination between Tren de Aragua and any senior leaders in the Maduro administration, although it did state that the permissive environment in Venezuela allowed drug gangs to flourish, many of whom are from Colombia.

The report drew on information from all 18 agencies that comprise the US Intelligence community.

The US government, despite public statements by Trump and Rubio, has provided no evidence to refute this large body of accepted work among journalists, academics, NGOs, and even US law enforcement agencies.

“I don’t care what the UN says,” said Rubio in a press conference on Wednesday in response to a question from a reporter, “the UN doesn’t know what they’re talking about.”

Conflating the ‘War on Terror’ with the ‘War on Drugs’ to expand Presidential power

Some experts have posited that the drone strike on the boat the US government claims was engaged in narcotrafficking is a fundamental change in US protocols on drug enforcement in the Americas. “The opening shot of a new war on drugs”, shouted a Vox headline this week.

Other outlets, like CNN, reported anonymous rumors of Trump mulling military strikes on “cartel targets” within Venezuela. And perhaps that isn’t untrue. Trump has dreamed of military strikes on organized crime groups since his first term in office.

To me, however, this seems like a misreading of the ongoing situation. While it’s clearly true that Rubio and Trump want to be perceived as taking a populist strongman stance on drug enforcement, if cutting off cocaine shipments to the US was really their primary goal, they would have positioned the heavily armed navy armada a few hundred miles west.

This seems like a darker project: a combination of two long-running destructive policies that have historically been used as a pretext for violently enforcing US geopolitical goals — the “War on Drugs” and the “War on Terrorism.”

Trump and Rubio are trying to build a perception that these issues are such a dire threat that the administration must seize emergency powers. They want to justify not only the use of the “Alien Enemies Act” to deport Venezuelan citizens to prisons in other countries, bypassing any need to present evidence, but also to claim the power to extrajudicially kill anyone they deem a member of those organizations.

And they have demonstrated that they will do so, anemically using claims of “terrorism” to justify it.

The disinformation being pushed about the Tren de Aragua is a crystalline example of this conflation. The US State Department is silent about the South American organizations responsible for the lion’s share of cocaine distribution, principally in Colombia and Peru.

They have no fancy names, like the ‘Cartel de los Soles’, and most do not have a designation as terrorist groups by US officials. Instead, the US is broadly targeting a group that does indeed engage in organized crime across the continent, but when compared to other actors, like Colombian or Mexican narco groups, it is a minor player even in the countries where they hold an organized presence — which is in itself a minority of countries in the region.

But Trump and Rubio have made them the face of terror, the face of the drug threat, and even an “internal enemy” in the US itself, despite the fact that they have next to no organized presence in the country.

Is there an outside chance the 11 people on that boat were tangentially related to the Tren de Aragua in some way? I do not reject the possibility. It is a “non-zero chance” as analysts are so often fond of saying.

But we have no evidence. And some claims by the Trump administration defy not only the broad consensus among people like myself who study this for a living, but also hard data collected as part of drug seizures and the information of US law enforcement.

It is much easier to imagine this as yet another authoritarian power grab by a president who has seized every opportunity for executive power expansion within his reach.

Editor’s note: The destruction of a civilian, and apparently unarmed, vessel was also likely illegal under US law, but it is our experience at PWS that doesn’t matter much in practice. Once precedents are set, states tend to find justifications for their actions. We do not want to dismiss the importance of conversations about US law regarding military actions, but for immediate material purposes (and clearly in the mind of Trump himself), this is largely irrelevant.

You can also donate a one-time gift via “Buy Me a Coffee”. It only takes a few moments, and you can do so here.

And if you can’t do any of that, please do help us by sharing the piece! We don’t have billionaire PR teams either.

Hasta pronto, piratas!