Who exactly ARE the armed groups in ceasefires with the Colombian government?

What do they want? Where did they come from? How powerful are they? We break it all down in this two-part series

Colombian President Petro Gustavo has announced ceasefires between the government and four armed groups in Colombia. Although legally, it isn’t yet clear how that will actually work in accordance with Colombian law, as Emily Dickinson, senior Colombia Analyst for the International Crisis Group, explained in depth in this great twitter thread, the announcement does represent a political and symbolic victory for Petro’s “Total Peace” plan in Colombia.

Petro has promised to move away from the military strategies of past administrations, which have only exacerbated a years-long trend of increased violence in the country without deterring the growth of criminal groups, and instead conduct direct negotiations with criminal groups themselves.

As Pirate Wire Services reported last month, despite claims from Petro on New Year’s Eve that an accord had been reached with the largest rebel group in Colombia, the National Liberation Army (ELN), that claim was quickly denied by ELN themselves, leaving his administration somewhat red-faced in the days that followed.

ELN and the government are set to resume a second round of peace talks this month in Mexico City.

None of the four groups that have announced ceasefires have any formal written agreement with the government. The truces are rather informal, and have been declared without any protocols.

But moving beyond legalities and the political ramifications, who are these armed groups? Where do they come from? What do they want?

We are so glad you asked, because we have all the important info right here. This will be the first installment in a two part-series looking at the armed groups involved in peace negotations: their motives, their modus operandi, and their relative power.

Part one deals with the two criminal groups who have their origins in right wing paramilitary forces from Colombia’s civil war. In next week’s installment, we examine the left wing rebel groups— factions who in the criminal underworld, are bitter enemies.

Meet the Paracos

Paraco is just slang for “paramilitary”, and technically could apply to every armed group on this list, but in Colombia when people use the term they are usually referring to the paramilitary death squads that fought on the side of the government during Colombia’s 52-year civil war.

The largest, and most infamous of these groups was the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). Although the existence of private right-wing military groups goes back to before Colombia’s civil war, their popularity and strength grew rapidly in the late 80’s. Originally funded by drug cartels in Medellin, later iterations of these groups enjoyed direct support from the government as well.

The government often used them as proxy fighters against rebel forces, and even coordinated directly with the groups as part of infiltration and military actions. AUC however, during the war became an infamous death squad, as well a sophisticated network for drug trafficking, and worked directly with high-level generals in Colombia’s army as part of “False Positives” scandals, in which thousands of innocent civilians were killed, and then reported as rebel fighters as part of a government conspiracy to increase official casualty counts.

AUC forces, along with scores of other paraco groups, were dissolved in the early 2000’s and fighters were given immunity from their crimes as part of the demobilization process. In theory, they rejoined civil society. In practice however, many of these fighters accepted immunity for their past deeds and simply set up new criminal enterprises, often with deep contacts in Colombian security forces.

And for many years, the government largely looked the other way as these groups expanded, fighting leftist rebel forces for territory and control.

One of these groups, which over the years has been called many names, has grown to become the largest criminal enterprise in Colombia— the Gaitanista Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC by their Spanish initials).

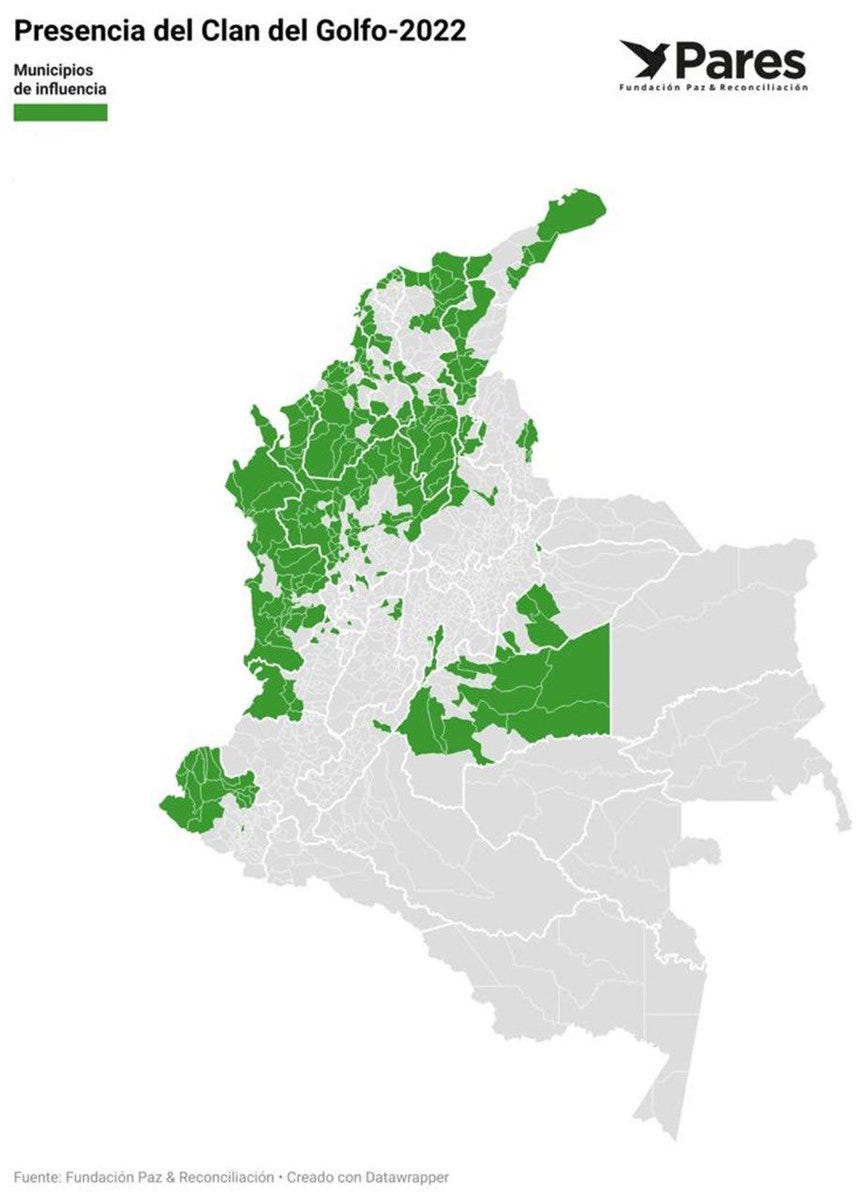

Previous administrations, which didn’t like to draw attention to AGC’s origins in the right-wing death squads that supported the government, preferred to call them the “Clan del Golfo”.

Locals in the regions where they operated often called them the Urabeños, a name drawn from the region where they were founded, Urabá.

By whatever name they are called, the group was founded by Vicente Castaño, who in 2006 broke away from the AUC demobilization process, and rearmed with two of his lieutenants: Ever Veloza Garcia, alias “HH,” and Daniel Rendón Herrera, alias “Don Mario,” the former finance chief of one of the wealthiest paramilitary factions in the country, the Centauros Bloc of AUC.

The group quickly secured regions along the Panamanian border, the most lucrative smuggling route in the country for cocaine headed north, and used the profits to build a criminal empire that has extended its tendrils into every aspect of economic activity in the country— from mining, to money laundering, to vote-buying, to extortion, and also made considerable investment in legal enterprises as well.

AGC operates a bit like a franchise: hundreds of semi-autonomous local cells enjoy a level of autonomy, and operate independently, but still in theory answer to a leadership structure in the northwestern coast of the country.

Despite years of claims from police and army forces, a series of killings and arrests of top-level commanders, a tactic police have called “the kingpin theory”, has not slowed AGC’s rapid rise in either power or territory.

Last year, one AGC’s top leaders, Dairo Antonio Úsuga David, alias “Otoniel”, was arrested by Colombian forces and extradited to the United States, where in January he pled guilty of narcotrafficking charges. He told US prosecutors that he was the mastermind behind moving “thousands of tons of cocaine, perhaps even hundreds of thousands”.

In retribution for Otoniel’s arrest, AGC shut down nearly a third of the country last year, in a coordinated violent action they called an “armed strike”.

AGC maintains extensive connections within Colombian security forces, with high level police officials on their payroll, and deep contacts within the Colombian military. They also have substantial connections with legitimate business communities on the northern coast, as well as in Medellin, as well as non-political mafia groups in both regions.

AGC has, at least publicly, agreed to a ceasefire with the government. AGC spokesperson Albeira Parra told the Colombian press that the group “Welcomes all peace efforts and has ceased hostilities against the government.”

The government has questioned whether AGC is really abiding by a ceasifre however, citing attacks on police forces in their territories.

AGC, for their part, has made public comments claiming the government isn’t abiding by the ceasefire either. This may be in part due to their status under Colombian law as an organized crime group- police knowingly ignoring ongoing crime efforts is illegal. Despite public claims of a truce, the Ministry of Defense is bound by the Constitution to continue prosecuting them.

“AGC has a leadership structure,” said Dickinson, “but it isn’t clear that all groups will answer a call for demobilization. We will simply have to wait and see.”

Many experts that spoke to PWS as part of our coverage hypothesized a peace process with AGC as similar to Colombia’s peace deal in 2016 with the FARC, where splinter groups broke away from central leadership and refused to recognize a truce.

In the meantime, AGC’s power continues to grow.

Self-Defense Conquistadors of the Sierra Nevada (ACSN)

Though less well-known than AGC outside of the region where they operate, and much smaller in both numbers and territory, the Self-Defense Conquistadors of the Sierra Nevada (ACSN) are also descended from AUC paramilitary forces.

ACSN was founded by Hernán Geraldo Serna, in Magdalena, on Colombia’s northern coast from the ashes of the Bloque Resistencia Tayrona of AUC in 2004. Originally known as the “Carribean Office”, and later “the Pachenca”, Serna originally created the group to control maritime cocaine smuggling routes from the Atlantic coast.

The group clashed with AGC in its early days before later striking a power-sharing deal with their paraco cousins, which fell apart in 2019. The two groups have been in open conflict ever since.

Aside from narcotrafficking, the group also imposes “taxes” - extortion payments- on local businesses in the tourist rich regions they control, a territory which also stretches into the neighboring departments of Cesar and Guajira, which borders Venezuela.

They have been responsible for the murders of a number of environmentalists who oppose commercial developments in Magdalena, projects for which ACSN gets a cut as part of their extortion schemes.

In addition to extortion and smuggling, they also generate money from land sales. Often displacing owners or even entire communities through violence, then using third-parties to acquire the land at low prices, which is then resold for profit.

In addition to being at war with AGC, They are also at war with ex FARC dissidents group Bloque Magdalena Medio, also based in Magdalena. ACSN, despite having small numbers, has managed to stave off competing organizations through their deep ties in the region, which go back decades, as well a stronghold of control in the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Their territory is strategically important as the main land route from Colombia’s biggest coca-producing region, Catatumbo, to maritime smuggling routes on the northern coast.

The group has publicly agreed to disarmament negotiations as well as a bilateral ceasefire with the Colombian government. However, this may be largely meaningless as the group has never conducted military operations against Colombian security forces— though they have targeted individual police via their network of hitmen across the coast.

These attempts have historically been made as retribution or intimidation rather than as open warfare against the Colombian state.

The Big Headlines in LATAM

We have addressed Peru in every newsletter so far in 2023, so we are going to avoid that this week, though protests continue. Suffice to say, it’s still a mess.

Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro has applied for a six-month US tourist visa. Bolsonaro has been staying in Florida since 30 December, after he fled Brazil in the wake of losing presidential elections by a razor-thin margin.

He has come under increased scrutiny after his supporters attacked Congressional and Judicial buildings in Brazil, calling elections fraudulent. An official investigation in Brazil has named him as ‘person of interest’ in court proceedings, and issued warrants for two of his former advisors.

Bolsonaro has condemned the attacks and denied any responsibility for their planning.

A group of off duty police in Haiti rioted in the capital Port-au-Prince, protesting inaction over gang attacks on police stations and officers.

The National Union of Haitian Police Officers says 14 men have been killed since the start of the year in various attacks on police stations. In a joint protest, the group, along with civilian protesters managed to breach the city’s airport, as well as surround the Prime Ministers’ residence.

Spanish concept of the week:

SPANGLISH! The word is sometimes used in English to mean tarzan-like efforts by English speakers to communicate to Spanish speakers (like “Donde es el mopo?”), but in reality describes a sort of hybrid language used by speakers fluent in both languages, with very interesting results.

Some people hate it, considering it a dilution of pure Spanish, or pure English, but we think it’s really cool! Language is always evolving, and for speakers who grow up in a household where two languages are common, a hybrid shorthand was inevitable.

Some examples of English grammar or sayings making their way into Spanish:

The most common example I hear in Bogota is “man”. I hear the english word even more commonly here than “hombre” when I’m out and about.

Ese man me está mirando raro - that man is looking at me funny.

This is a pretty simple example, and unlikely to turn any heads. But some hybrid sayings might attract more ire, though we do hear and see their usage.

In English, things make sense, but in Spanish things have sense—

Ese argumento tiene sentido.

However, in informal use, particularly in social media, we have begun to see examples of the two forms combining. Using hacer sentido, “making sense” translated literally into Spanish.

We’ve also heard this crop up with the verbs “gustar” and “amar”, to “like” and to “love” respectively. Wendy M broke this down for us nicely on twitter this week: