Will Bolivia’s ex-interim president be convicted of coup-mongering?

Human rights defenders agree Jeanine Áñez must answer for atrocities on her watch. But some observers have doubts about the handling of her trial

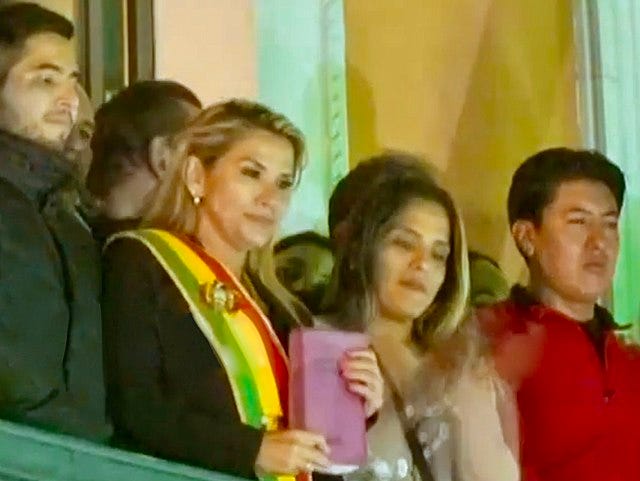

On Thursday, 10 February, Bolivia’s former interim president Jeanine Áñez was due to have her virtual day in court over accusations that she participated in a coup to overthrow her predecessor, Evo Morales. Although she was appearing via video link from Miraflores prison, the La Paz street outside the courthouse was packed: demonstrators waved placards bearing photos of the victims of human rights violations during her presidency, chanting “It’s not vengeance, it’s justice!”

Separated from them by nervous-looking riot police, Áñez’s supporters waved signs saying “Freedom for Jeanine!”

Both sides would leave disappointed: the trial was postponed due to procedural errors. But as pressure from victims, survivors and activists grows and the ex-president enters her tenth day on hunger strike over claims that she’s a political prisoner, it’s only a matter of time before the issue is thrashed out in the country’s judicial system.

The trial comes as a UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of lawyers and judges visits the country at the government’s invitation. After Áñez’s arrest last March, Human Rights Watch expressed concern that Bolivia’s justice system was “pliant to those in power” under Áñez, Arce and Morales alike.

Áñez became president on 12 November 2019, two days after Morales, an Indigenous leftist who ruled for almost 14 years, was forced to step down. Controversial allegations of electoral fraud had sparked deadly nationwide protests, the police mutinied, and the military “suggested” that he resign.

Bolivia had no president for two days. Following a series of murky negotiations, Áñez, a politically obscure far-right senator from the tropical department of Beni, assumed the presidency based on her role as second vice-president of Bolivia’s senate.

Just days after her inauguration, she signed a decree relieving the security forces of legal responsibility for actions taken to “pacify” the country, which was still gripped by protests. As if on cue, they gunned down 10 demonstrators as they marched through the town of Sacaba. Four days later, they committed another massacre, killing 11 more protesters who had been blockading a gas plant in the El Alto district of Senkata.

During the year her interim government lasted, many politicians from Morales’ Movement Towards Socialism party (MAS, by its Spanish initials) were persecuted and imprisoned or went into exile. Violent right-wing biker gangs carried out racist attacks on Indigenous people. Human rights defenders faced persistent attacks and threats: a woman walked into the office of the Cochabamba human rights ombudsman’s office with a loaded gun in her bag and when Argentine rights defenders travelled to Bolivia, images were circulated online of Che Guevara’s corpse with the words: “This is what happened to the last Argentine to meddle in Bolivia’s internal affairs”.

When protesters blocked roads across the country mid-pandemic to demand free and fair elections, the government claimed that the resultant delays to medical supplies were killing people. They accused Morales of orchestrating the blockades from his political asylum in Argentina and reported him to the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity (the accusations were dismissed this week).

MAS was voted back into power in October 2020 in a landslide, this time with former finance minister Luis Arce in the top job. Áñez was arrested on charges of terrorism, conspiracy and sedition in March 2021. Now, many in the human rights community feel that the trial is a crucial step towards justice.

“Mrs Jeanine Áñez isn’t a political prisoner, she’s a politician who’s in prison,” tweeted Paulo Abrão, former executive secretary of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. “The struggle against attacks on democracy goes hand in hand with the struggle for human rights. Bolivian justice has taken a step in favour of the victims and a key step towards non-repetition.”

But others are concerned that Áñez is not getting due process, which they fear could undermine faith in the proceedings and set a dangerous precedent.

The chaotic events spanning Morales’ resignation and the early days of Áñez’s presidency are likely to prove key in the coup deliberations. In the current trial, she stands accused of breach of duty and adopting rules contrary to the state constitution and laws. Along with Morales, vice president Álvaro García Linera and the leaders of the senate and deputies had resigned.

Bolivia’s constitution doesn’t establish succession beyond these figures, stating instead that congress should convene to determine a new leader. But Bolivia’s constitutional court issued a communiqué stating that Áñez could rise to the top job, drawing on a ruling made in 2001. Her lawyers claim that this means that her presidency was constitutional. But her opponents argue the court’s statement didn’t constitute a formal ruling.

A subsequent legal decision on a fight over who was the rightful leader of the deputies at the time could also complicate the case, according to Dr Jorge Derpic, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the University of Georgia. Head of deputies Victor Borda resigned after a mob of anti-MAS protesters burned down his house and kidnapped his brother. Deputies vice-president Susana Rivero, also of MAS, announced her intention to resign, prompting second vice-president Margarita Fernández to claim that by rights, the position of head of deputies should have gone to her.

But last year, the constitutional court denied Fernández’s claim on the grounds that Rivero was still technically in her job by the time Áñez took power. That raised the question: if the court recognized that Rivero was entitled to lead the house of deputies when Áñez was sworn in, didn’t that mean Rivero was ahead of Áñez in the chain of succession?

Another point of controversy is the decision to prosecute Áñez in an ordinary trial. In Bolivian law, ex-presidents face a special process known as a “trial of responsibilities”, which was used to convict former dictator Luis García Meza in 1993. Prosecutors argue that the plotting and conspiracy she’s being tried for took place when she was not yet president, so she can be tried as an ordinary citizen. The two main concerns are that refusing a trial of responsibilities is a violation of due process and that she should not face multiple trials over the same series of events, under the principle of concurrent offences.

“Let’s say a burglar gets into a house, steals something and shoots the owner. You’re not going to have a trial for burglary and another for shooting the owner,” Derpic said. “You’re going to merge them.”

However, a trial of responsibilities would require a two-thirds supermajority in Bolivia’s senate, and the government might not be able to secure the votes it needs. Rights advocates’ worst fear is that an ordinary trial is discounted because Áñez was president, the senate votes against a trial of responsibilities, and she walks free - although she could still face charges through international courts.

Human rights probes have unanimously concluded that the Bolivian security forces were responsible for the killings in Senkata and Sacaba. A group of independent experts from the IACHR said in an August report that they had “no doubts” about classifying both incidents as massacres. Some victims’ groups have protested that the coup trial is being privileged over the massacre investigation. But those who support the current trial argue that questions about how Áñez came to power are essential to Bolivia’s democracy, and that it’s inextricably linked with the human rights violations as part of a violent right-wing power grab.

Derpic agrees that Áñez should stand trial for the massacres. But he feels the approach to the current trials means that broader issues for which MAS also bears responsibility, such as Morales’ decision to ignore a 2016 constitutional referendum and seek the right to indefinite re-election, risk being “swept under the carpet”.

“If we don’t put some boundaries to what can and cannot be done through the judicial system, then that very same judicial system is not only used against the right or the political center-right opposition, it’s used against Indigenous peoples, it’s used against social organizations, it’s used against the anti-authoritarian left which was part of the uprising against Evo, or coup, if you want to call it that,” he said.

“That’s the biggest danger.”

Stories we’re watching:

Alex Saab, the Colombian billionaire who was arrested by the US while acting as a Venezuelan diplomat, has actually been an informant for the DEA since 2019, according to files released by prosecutors on Thursday. Saab’s lawyer denies the accusation, but previous court filings by another of his lawyers request protection for Saab as “an informant, who could be endangered by his cooperation”— seemingly supporting the DEA claim.

Former President of Honduras Juan Orlando Hernández was arrested by Honduran officials over drug charges filed by the United States. The US, who supported Hernández during his term in office, has requested his extradition to face prosecution, claiming that he used the powers of the presidency to organise a mass cocaine smuggling operation.

What we’re reading:

At least five members of the gang trafficking the adulterated cocaine that killed 24 people in Argentina were members of the police force, La Nación has found

Spanish words of the week:

testaferro (m): Figurehead, frontman

comparecer: to appear or present oneself in front of an official body

alijo (m) : A cache or stash, as in "Josh's super-secret stash of capybara pictures"